[Disclosure: AgFunder—the parent company of AgFunderNews—is an investor in Modern Synthesis]

Designer bags… made by bacteria?

Founded by ex-Adidas designer Jen Keane (CEO) and synthetic biologist Dr. Ben Reeve (CTO), London-based Modern Synthesis recently teamed up with Danish fashion brand GANNI to unveil GANNI’s signature ‘Bou Bag’ using a leather-alternative produced, in part, by bugs.

Rather than growing mycelium—the filament-like root structure of mushrooms—to make its biomaterials, Modern Synthesis combines nanocellulose created by sugar-eating bacteria, with natural textiles such as hemp, linen or lyocell.

According to Keane, the process is “similar to how rebar is used to reinforce concrete” and generates materials that “can be processed on the same equipment as conventional textiles.”

But how efficient are bugs at creating bags, and how scalable is Modern Synthesis’ patent-pending technology?

AgFunderNews (AFN) caught up with Keane (JK) to find out…

AFN: How did you get interested in biomaterials?

JK: I went to Cornell and studied fiber science and apparel design, which was kind of at the intersection of textile technology and science with fashion design. It was quite a niche program but it led me into the sportswear industry where all the innovation in textiles has been happening over the last decade.

So I worked for a short time for Nike but spent most of my career at Adidas in Germany, where I worked predominantly as a material designer and developer. And then I worked to set up the material design direction team where we looked across the brand at strategic initiatives around materials. During that time I worked on a project called Parley for the oceans, which was an ocean plastic collection that integrated recycled ocean plastic [into fashion goods].

And I think that was the time that we realized the magnitude of the problem around materials and how it was driving a lot of the industry’s total impact.

But also, it became clear that just recycling plastics or synthetics wasn’t the end solution and that we really needed to rethink our materials supply chain and the materials that we’re using in our every day lives.

And that drove me to London. So I came here to do an Master’s in material futures at [arts and design college] Central Saint Martin’s, which has quite a well-renowned program at the intersection of design, science and technology. And that’s where I got introduced to my cofounder Ben, our CTO, who is a bioengineer from Imperial College London.

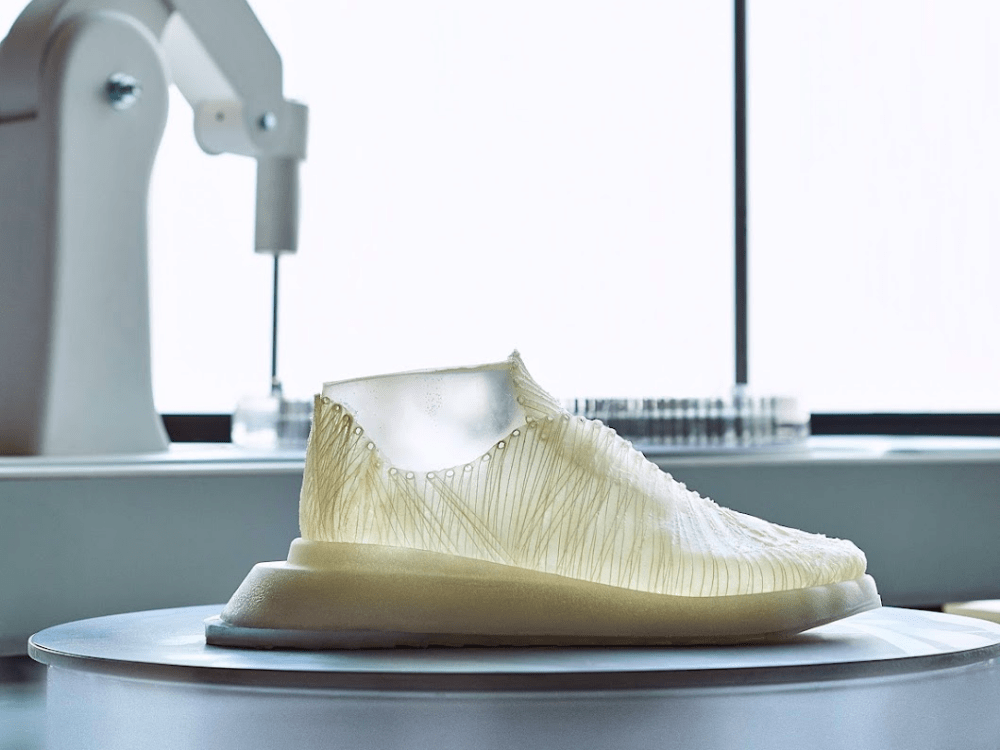

And that inspired my own work… and so I grew a shoe, as one does (!), with an early version of our technology and then after having a really positive response from the industry, it was a question of how could we take that concept, make it a reality, and really scale it? And that’s what led into Modern Synthesis.

AFN: What else was around in the biomaterials space when you first started experimenting with them?

JK: It was super early at that point, although there had been a lot of experimentation. So for example Suzanne Lee was quite famous for her Biocouture experimentation. She was the first to look at bacterial nanocellulose or kombucha materials for fashion applications.

I think at an industrial level, the only things that were available were things like Piñatex [a leather alternative made of fiber from upcycled pineapple leaves] and there were some experiments with materials from spider silk. But it was still in the early stages of development and hadn’t been able to hit any sort of performance requirements.

When I was doing my Master’s [2016-18] I knew that Bolt Threads, Ecovative and MycoWorks were using mycelium [to make a variety of materials] but it was all very nascent.

AFN: Tell me about the genesis of Modern Synthesis

JK: We officially started the company in 2019, but it didn’t really get started until 2020 during the pandemic. I was actually working as a creative resident at Bolt Threads in early 2020 and then when the pandemic hit, that was really the kickstart for Ben and I to jump full time into the company. Everything was shutting down and we were like, OK, we’re going to do this!

So we worked with a material called bacterial nanocellulose produced by bacteria isolated and sequenced from kombucha tea by a team of scientists working with Ben at Imperial College. These bugs produce nanocellulose, which has been used for several years in medical applications, beauty and food.

Why scientists were interested in this particular bacterium is because it’s a very efficient organism, so it creates a lot of material with very little input. But the fibers themselves are also really interesting.

Cellulose is the building block of the natural world; it’s the most abundant and versatile building block; the main ingredient in cotton, linen, wood, paper, and a lot of the materials we have around us today. But nanocellulose is the strongest, finest form of cellulose, and because of its size and the strength of the fibers, which at the fiber level are 8x times stronger than steel, they create really strong nano networks.

The initial version of the technology—when I grew my first shoe—was looking at how you could biologically use those nano networks to create a fabric structure by combining them with a traditional textile scaffold.

Since then, we’ve made a lot of progress, and are now able to enhance those nano structures outside of the biological process and do a lot more with different combinations of textiles and process them on more commercial equipment.

AFN: Do the bacteria naturally produce nanocellulose pretty efficiently or are you genetically engineering them?

JK: They naturally produce it very efficiently, so it’s already produced commercially for various applications such as wound healing applications and hydrating face masks. And so as bacteria go it’s a pretty easy one to scale and it’s already been optimized.

But we have explored [using] synthetic biology to see if we can get the bacterium to do other things such as produce [the black pigment] melanin, for example.

There are a lot of cool ways you can use biology to enhance the material, but for our current process we use the natural strain of the bacteria because it’s easier and we want to focus on scaling before dropping in some of these other technologies.

AFN: How do you create your biomaterials?

JK: In the beginning, we were growing the bacteria together with the textile [see the ‘shoe’ image below].

Now, we’ve separated our process into three steps to make it far more scalable.

The first is growing the nanocellulose in fermentation vessels. And then we take the nanocellulose, enhance those nanostructures to alter things like pliability and strength, and finally we combine it with the textile [eg. linen, hemp etc], where we can also change things like the feel and thickness of the textile.

This means we can work with partners who are growing nanocellulose already. Anyone can grow nanocellulose and we believe there will be a robust industry in that. Where our expertise and our patents lie is in the transformation of that nanocellulose into really high value, low impact materials.

We are able to manipulate and enhance the nano structures through our patented technology, and further improve properties with other bio-based ingredients.

Next, we can use equipment that is already used in conventional textile processing to combine the nanocellulose with a natural textile and process the final materials, which means we can integrate more quickly into existing supply chains.

So they go through, for example, a drying, embossing, and finishing process as other textiles are formed today, with the key distinction being our materials are entirely petrochemical and plastic-free.

We’re unique in that we’re the only ones that combine nanocellulose with textiles in this way, and we’ve patented that. It’s a bit like how rebar enforces concrete. You have that core structure from the textile, which is enhanced by the [nanocellulose] biofilm that we formed together with it.

So those interactions allow you to make a wide variety of textiles, from drapable materials to more transparent films, to a more robust textile that’s heavier and more leather-like.

AFN: How scalable is your process?

JK: Companies using mycelium have had to work on both scaling the production of the raw material and scaling the material processing. For us, the nanocellulose production side of things has already been scaled, so we just have to focus on the material processing side, which is really our core IP and what’s really innovative. So this means we’re able to reduce the amount of CapEx required to scale and scale a lot more quickly.

Leather can range in cost from anything from $10 to $100 a square meter. And so different qualities, different types of these materials go into different applications. But we are confident that at scale, we can hit the mass market versions of these materials.

AFN: So what kind of materials are you making?

JK: We can make a wide variety of different coated textiles, but we’re initially targeting replacements for leather because there’s an enormous need for animal-free alternatives. And then we’re looking at replacing polyurethane-based vegan leathers or other coated textiles and synthetic coated materials.

After that we can look at the automotive industry, things like dashboards, although you need to be at a larger scale than we are now to meet the demands of that industry.

Beyond that there are performance coatings and other functionalities that we can add. Nanocellulose has a lot of benefits in terms of reactive materials, adaptive capabilities, embedding certain performance features that we’ve already shown some really interesting progress towards.

AFN: What IP do you have?

We have three patents pending at the moment, and extensive trade secrets around our processes.

AFN: What’s your manufacturing set up?

JK: Right now we’re able to do all three steps internally in-house at a miniature scale and the next phase is scaling up our pilot capabilities, so going from small sheets to a larger scale for more prototyping. We’ve had incredible demand from the fashion industry, but we’ve been limited by the amount of samples we can produce.

Then we’ve identified partners here in the UK and in [mainland] Europe, who have full-scale equipment that we can utilize. So how we scale will be a combination, most likely, of doing some production ourselves and using contract manufacturing for certain parts of the process.

AFN: How have you funded the business so far?

JK: So far we’ve raised about $5.6 million, and now we’re gearing up for our next phase of growth to expand our product facilities and get to commercial scale production on full size lines so we can launch with our partners.

We launched our first public showcase in collaboration with Danish fashion brand GANNI, and they made a public commitment with us targeting a 2025 commercial launch, so we’re laser focused on getting the material ready for those first commercial launches.

AFN: How are investors looking at this space?

JK: Everyone’s talking about how hard it is to raise money, but I’ve heard some really positive things in some of the conversations that I’ve had. People are still excited about biotech and the circular economy and everyone realizes that the opportunity in biomaterials is enormous.

And because of the public traction that we’ve had, we’ve had a lot of inbound inquiries and excitement about what we’re doing. The industry has committed to moving away from the materials they’re using today by 2030 and there’s far more demand than there is capacity. And so at least in in our arena, there’s still a huge amount of interest.

AFN: Have the problems at Bolt Threads dampened enthusiasm from investors?

JK: With what’s been happening at Bolt Threads, I think everyone was asking themselves, is this scalable, and how much money do you need to scale it? And that’s why we’ve really designed the process to minimize CapEx by using existing equipment so we don’t have to raise quite as much.

We’ve also shown that based on our models, we can hit price parity with most leathers and premium polyurethane coated textiles at scale. It’s just a journey to get there, so we’ve been really thoughtful about which markets we enter first.

The other thing I always like to point out is that there are differences between all the players and the technologies [in the biomaterials market] in terms of scalability but also performance. We’ve had some really incredible performance results. Recently we’ve hit over 200k flex, which is how many times you can bend materials back and forth, which is one of the key criteria for entering the footwear market. So the performance of our material is really quite special.

Likewise, versatility is often underplayed, but if you think about how fashion companies or brands in general work with their material suppliers, these are long term relationships. So the ability to offer different weights, different thicknesses, allows you to get into more of the product range and offer seasonal newness. We can offer a much wider array of aesthetics and functionalities than most of the other technologies.

AFN: What’s driving interest in your materials?

JK: We’re currently working with multiple premium and luxury brands plus we have 35 major brands in our pipeline.

Every brand is slightly different, but at the end of the day, they are all being pushed to reduce their overall environmental impact. In some cases, consumers are also pushing them away from animal-based materials, plus there’s an increasing awareness of microplastics and plastic pollution.

AFN: How do you and [cofounder] Ben [Reeve] split responsibilities?

JK: I think we really complement each other. He’s a brilliant scientist and very technically minded, experienced with IP strategy, and has a great mix of experience and understanding on the biological and the material science side.

So he’s definitely taken the technical lead, while I’m coming at this more from an industry perspective. I understand the mindset of the customer as I worked in the industry and talked to suppliers. I also understand the need to communicate not just the technical, but actually the emotional qualities and advantages of the products that we’re making.

AFN: What keeps you awake at night?

JK: You get growing pains at each juncture of the business, going from two to eight people, from eight to 16, from 16 to approaching 30 people, and scaling the human side of the business is really important and often underplayed.

When you’re at the early stage you need people that are adaptable, that can do a little bit of everything. But when you start getting into a slightly larger business, you need more management experience, and I think we learned that you need to be a bit more proactive about hiring. You need to think one step ahead so you can actually grow into the organization, as opposed to trying to retrofit it as you’re going along.