Editor’s Note: Sean McDonald is the former CEO and co-founder of Bitwater, a venture-backed automated insect farming startup that grew quickly from 2014 to 2018, then shut down abruptly for non-commercial reasons. He is now a managing partner at Supply Drop, a platform for disaster preparedness tools and training.

Aaron Ratner at Ultra Capital has been involved in the insect industry for years, and contributed ideas, edits, and quotations to this article.

Buzz Aside, Insects are a Legitimate Solution

After five years as a founder and CEO, I learned a lot about the insect farming/production industry. My former company – Bitwater – started with a prototype in my garage. It had twelve crickets, and a dollar store fan taped to the side. But the fan and the heat lamp were controlled by my laptop, and the system work. We grew from there to multiple facilities in the US, including an R&D facility in North Carolina with hundreds of IoT-controlled insect habitats. I had the opportunity to speak at events like the Ag Innovation Showcase and SXSW Eco and spread the word about the potential scale of this opportunity. As we grew, I was able to learn what successful venture deals looked like in the space; what project finance deals looked like; and what corporate leaders were and still are thinking about insects as feed.

I even had one very strange conversation — in a coat closet at a conference center — with an influential corporate executive about whether we could grow giant insects. “Can you 10x their physical size?” True story. (No. No is the answer.)

I had a front-row seat to the buzz — and the reality. It’s easy to criticize this industry and the entrepreneurs who drive it forward, for being full of hype. In many cases, that is true; but it’s part of a more complicated reality.

The truth is that insects do work for farming already – chickens are born with necks strong enough to peck insects as soon as they emerge from the shell – but they are also part of a speculative investment market. It is both true to say that insects are successfully farmed and that insect farming is mostly unsuccessful because a single bucket for “insect farming” is too big. Insects are farmed all over the world right now, just not at volumes that seem relevant in a world of 30 billion farmed animals and the many billions of tons of feed they need. But the technical advantages of localized supply chain and resilience to volatile climate swings will, I am confident, provide enough advantage that the world will one day be populated with insect farms, large and small.

The Not-So-Secret Sauce: Automation

Insects can be dangerous, and humans are dirty and problematic. Every player in the industry is working towards automation to reduce human intervention as much as possible. And either they’re attempting to scale that automation today or solve the problems that would be required to scale.

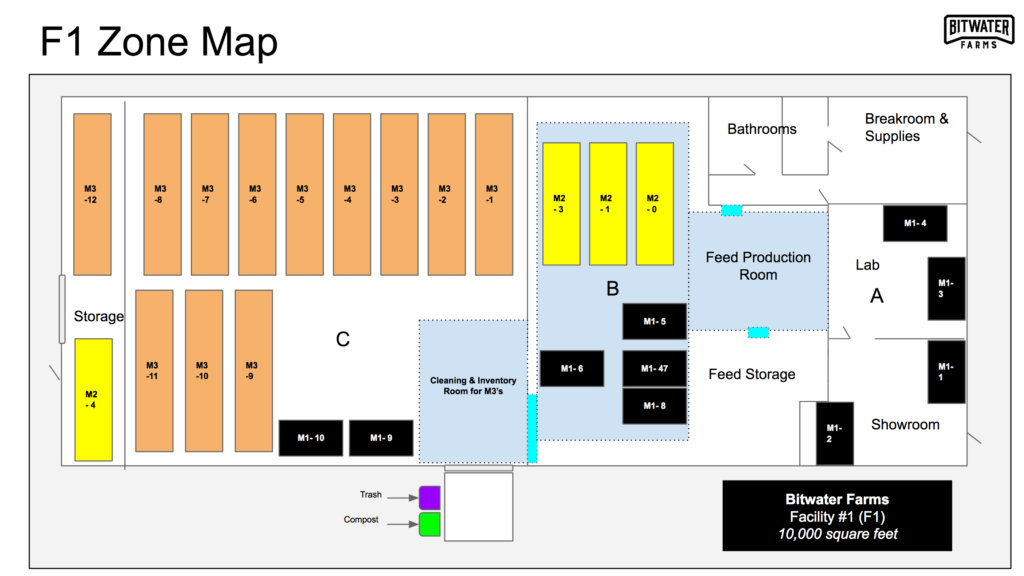

At Bitwater, we were somewhere in between. We were attempting to solve the problems that would make our modular insect habitats compatible with fulfillment center robots. If we could make a system that complied with the kind of robots that run warehouses, we could simply “piggyback” on that well-established platform.

We made progress, and got so far as having fully functional rolling farming habitats that were over twice the size of a modular shipping container, volumetrically, but weighed only 800 pounds above what the contents weighed. This made it theoretically compatible with the strongest warehouse robots, who could move these giant units from zone to zone. This allows a single zone for cleaning, a single zone for loading and unloading, and a rolling inventory of habitats that can be decommissioned, serviced, then brought back in an on-demand cycle.

In truth, the vast majority of commercially successful cricket farms are using what amounts to three-thousand-year-old techniques that include troughs full of insects growing on the ground, while most of the venture-backed startups are using methods that are zone-based automated environments, where software controls the temperature, humidity, feeding, air circulation and most of the safety and inspection procedures. There are myriad benefits of automation for insect farming: some that are broadly applicable like labor costs and contamination risks, and some are specific to insects such as preventing cannibalism and immediately addressing problems like mold.

I know many investors think that insect R&D taking place in small, insulated canvas tents known as “grow tents”, made ubiquitous by the cannabis industry, is not credible. That’s not the case. You can fill up a warehouse with insects using the eggs stored in one small grow tent — if you know how.

Mitigating Feed Volatility for Farmers is the Secret Ingredient to Dominance

We had a record in our CRM that I made 156 angel and venture investor pitches. I got to see the landscape, from “App Investors” wanting to dip their toes in sustainable agriculture, to the biggest conglomerates in agriculture. Had we continued to grow at Bitwater, we were on track to close with some big names in deals on the same trajectory as recent rounds like Ynsect’s. (Congrats on that!)

What I found, time and time again, is that the bigger the fund, the more sensible they found the notion of investment. I believe that the core value proposition – which was shaped in part by my former colleague Aaron Ratner at Ultra Capital, who was a Board Observer at Bitwater – for any insect developer is risk mitigation, and more specifically, feed price volatility risk mitigation. One of the biggest pain points for any farmer is the cost of their feed. Volatile price swings in commodity markets, and a volatile climate are making it increasingly difficult for farmers to profit from their business. Insect farming promises to produce a sustainable source of feed, year-round without external factors such as climate playing as big a role in prices. This is why we see billionaires, and billion-dollar multinational corporations, paying so much attention to the industry, I believe.

Solar is a Great Analogy to Find Growth Tactics

I’ve had the opportunity to talk to some leaders in the solar industry, on the technology and finance side, and there are a lot of similar dynamics in the two industries:

Mitigate distance-based risks: The fact that livestock feed usually travels hundreds or thousands of miles from farm to animal exposes it to a series of complex risks. Catastrophic weather events are becoming more common, and there is potential for volatility in fuel and shipping costs, as well as increasing volatility on international trade agreements. If, however, the majority of the protein and micronutrients, for example, at a poultry operation were coming from a few miles away at an insect rearing facility, most of those risks would be dramatically reduced. This is similar to solar where transporting energy long distances is no longer required.

Finance for the long term: Because commodities are almost certainly not high-profit goods, a strictly venture-based financing approach is extremely difficult. So other forms of finance that have mechanisms to share in flexible, distributable free cash flows become appealing if not imperative. The solar industry helped establish rapid approval project financing and I suspect that “retrofits” to insect production will become commonplace and easily accessible in the future.

Lock in the price: Most businesses would rather not be exposed to commodity price volatility. While some have complex hedging mechanisms in place to make it work for them, it’s still probably not optimal for their profitability or their stress levels. A big part of the great promise of insects is the potential to offer farmers a constant price over five to 10-year future periods. In a controlled environment, weather and international trade friction cannot impact an otherwise steady state of reliable production. Solar energy companies also lock in prices for their customers.

Risk Mitigation and Alternative Finance Go Hand-in-Hand

My background was in traditional tech startups, working mostly with software investors. As we built Bitwater, it became clear that we needed multiple types of finance to fit our business model. Seed and venture funding covers R&D very well but does not cover machines, heavy equipment, or long term offtake agreements with escrow accounts very well — if at all.

According to Aaron, “Project finance is starting to play an important role as a financing mechanism that enables commercial insect farming operations to scale production to meet the demand, and opportunity, presented by multiple verticals within the agriculture industry. Venture capital, private equity, and bank debt will always be valuable, but the developers who scale up rapidly will have figured out early on how to deploy project finance-level capital.”

That was my experience, and I think the industry as a whole will mature with a hybrid financing instruments, not just a one-size-fits-all “venture alphabet” (Series A through E…) model.

Insects are Dangerous — Like Everything Else in Ag

I left the industry because, in a cruel twist of fate, I developed a rare sensitivity to a part of the insect farming production cycle. It was not toxic the first few years, but as we started to raise hundreds of millions of insects at a time, my health problems reached an inflection point. I had to choose between my family and my career, and the choice was easy. While we still do not know exactly what was happening, I trusted my doctor’s advice: “It may not be this time, but one of these attacks is going to kill you.”

There are ample reports showing that some people, like me, have sensitivities to insect production. It’s critical that the industry addresses this issue. I expect that great organizations like NACIA and IPIFF will systematically approach these issues.

In the future, the industry will have good screening tests for workplace safety, and – like so many things – safety can advance dramatically with automation and robots. Ironically, our company was developing systems to deploy fully-automated insect systems, which would require little-to-no human intervention. That is the future of this industry: fulfillment-style robotics.

On-Demand Insect-Based Feeds

I believe the inflection towards dramatic growth will be when the companies scaling up their R&D today are able to provide a revolutionary product: a local, sustainable, on-demand feed nutrition system. Within the next few innovation cycles it will be possible to forecast, for example, a need for more methionine fourteen weeks out for layer chicken production using machine learning, then automatically program the increased production of insects rich in methionine to be at the appropriate lifecycle stage to be harvested exactly when they are needed.

This affords a new way of thinking about feed ingredients. Proteins and micronutrients can be not just fresh, but locally produced and priced consistently in a model like you might see in project finance and solar.

Again, Aaron: “Most major livestock and aquaculture feed producers and buyers are looking for large-scale, long-term dependable sources of sustainable protein to reduce the effects of commodity volatility on their businesses, most of which gets passed along to farmers as end customers. Industrial insect farming is positioned to meet some of that demand.”

Insects are a big idea. I could not go back to small ideas.

I was an unlikely cricket farmer. Prior to that, I had started and worked exclusively at data science software companies, with a focus on advertising and social network analysis. More concretely: I worked on advertising technology in Beverly Hills, in a highrise suite on Wilshire Boulevard. Then I met my now-wife, who runs Seed Spot, a social impact incubator. She persuaded me to focus on work that built a more sustainable world, solving real problems. The idea started with a focus on providing protein and iron for young children, and I still see that as the real promise here, post-commercialization and industrialization.

Now that I can’t have anything to do with the insect industry, other than occasional advice from afar, I have started to solve a problem I would not have had any mind for if I had not worked in agriculture. When I toured farms and ranches around California, drought and wildfire were a much more present effect of climate volatility. I have seen wildfires in five states now and been to the hospital for wildfire smoke inhalation twice.

That’s why we launched Supply Drop, a platform for emergency preparedness. We personalize, localize, and automate every step of the process to make it easy for people and companies to have the supplies and training they need in real-time to survive and thrive in the new normal of climate-related risks.

I hope AgFunderNews readers will listen to our latest podcast. It features a rancher and entrepreneur, Jaimie Stoltzfus, the founder of Cowgirl Meat Company in Montana. She is a wildfire survivor who talks about the unique preparedness challenges faced by ranchers and ranch moms.

Image credits: Royce Gorsuch and Colin Arndt