Jinal Surti is CEO at Epoch, which deploys earth observation and web3 technology to monitor and report on environmental outcomes at the first mile of supply chains and leverage global payment networks to tie premium payments to improvement in measured and quantified sustainability metrics.

Tim Rann is the managing partner at Mercy Corps Ventures, a family of funds focused on backing startups building solutions for climate adaptation and resilience in emerging markets.

The views expressed in this article are the authors’ own and do not necessarily represent those of AgFunderNews.

Agriculture and forestry-linked supply chains are responsible for more than 30% of global carbon emissions. Moreover, our global food system is the primary driver of biodiversity loss, with agriculture alone being the identified threat to 24,000 of the 28,000 (86%) species at risk of extinction. In our journey to addressing these planetary challenges, fixing these supply chains is critical.

Given that the farming and plantation of commodities in these supply chains account for most of the emissions, the focus naturally turns to tropical soft commodities such as coffee, cocoa, palm oil, rubber, timber, and even cattle, most of which originate in the Global South. At the heart of these regions lie the smallholder farmers – more than 500 million of them, where sustainability isn’t just a practice but a way of life.

The unsung heroes of sustainability

These smallholder systems are not sprawling industrial plantations but rather, patches of land less than 2 hectares (in some cases, less than an acre), typically managed by families or small communities. These farms are inherently more sustainable than their industrial counterparts; they practice intercropping, maintain higher biodiversity, use less fertilizer, and adhere to traditional agricultural practices that have stood the test of time.

The Drawdon project estimates that by adopting regenerative practices, including those already used by smallholder farmers, the global food system could reduce between 15.12 to 23.21 gigatons of CO2 by 2050.

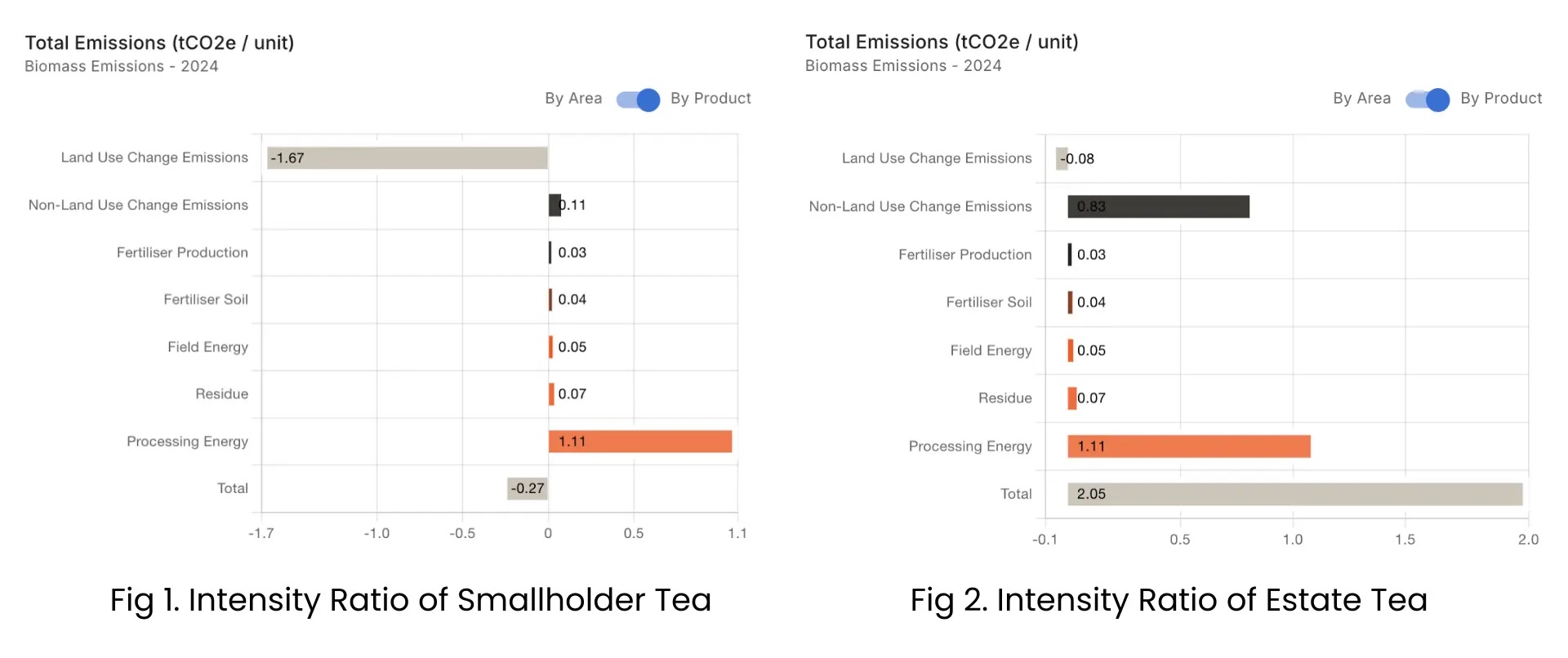

One of Epoch’s clients, Lujeri Tea Estates Ltd. in Malawi has a significantly lower carbon intensity tea of 1.51 kg CO2e/kg of tea vs. the industry average of 6.46. To improve it even further, it has been actively growing, supporting and promoting its smallholder supply base to its supply chain partners. For good reason – a side by side comparison of smallholder vs. estate tea production shows smallholder production to be a much lower carbon intensive production model, mainly due to the prevalence of agroforestry in smallholder plots:

Lujeri tea grown on smallholder land has an intensity ratio of -0.27 (i.e. every kg of dry tea produced from their smallholder suppliers sequesters 0.27 kg of CO2e), compared to the estate-grown tea’s intensity ratio of 2.05 (i.e. every kg of dry tea produced from estate properties emits 2.05 kg of CO2e) precisely because small-holder systems run on a low input, low output business model, which is a lot more sustainable.

Despite these green credentials, though, most smallholders face significant challenges. Beyond the existential threats from climate stresses and shocks, there remain persistent barriers for farmers to grow their businesses sustainably, including access to finance, markets, and productive assets.

On top of this, a new potential complication is looming: regulations such as European Union’s Deforestation Regulation (EUDR), Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD), and Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), which require businesses to monitor and report on environmental metrics of their supply chains.

An unfortunate consequence

Because global businesses operating in the agricultural and forestry sectors are now required to report supply chain sustainability metrics, and because most of their environmental footprint is associated with the first mile of their supply chains, they are turning to their suppliers for this data, something that smallholders are not readily equipped to furnish.

Global businesses face major consequences if they are unable to produce this data – up to 4% of annual revenues in the case of EUDR.

As a result, global agrifood players have to make hard decisions about their supply chains, specifically on the level of risk they are willing to accept in sourcing from geographies, value chains or farmers with poor, fragmented or limited data. While some players are working together with their first-mile partners (farmers) to produce this data, others are simply cutting out parts of supply chains with low data, locking smallholders out of their supply chains in favor of industrial producers.

A data dilemma

The crux of the issue lies in the data—or the lack thereof. Smallholders in the Global South are often not equipped with the tools, connectivity or incentives necessary to provide the detailed environmental impact data now demanded by their buyers.

Even if they have good records of practice data (such as plot geolocations, fertilizer use, fuel use and more), access to Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) tools that can process the practice data to produce environmental metrics remains out of reach for smallholders.

The bias in MRV systems

Today, MRV systems are primarily tailored for “Western” (or Global North) markets. These systems, often developed with industrial farmers or a multinational Consumer Packaged Goods (CPG) company in mind, come with high costs and a focus on selling data rather than sharing it. There is rarely, if ever, any meaningful incentive or compensation for farmers whose data is being requested or extracted.

This model fails to accommodate the needs of smallholder farmers in developing regions, where affordability, accessibility, and simplicity are critical for adoption. Moreover, many of these MRV systems are “black boxes”— their methodologies (to convert farm input data to environmental metrics) are not transparent, and the data, once harvested, often does not remain in the hands of the farmers, further reducing their power in the value chain, while adding greenwashing risk for the buyers.

There is a vested interest for downstream value chain players to maintain this opaque system, as it solidifies their market power and maintains information asymmetries. This status quo also reduces the public scrutiny of sustainability data and commitments.

The case for an open, cheap (free?) MRV

An open-data approach to environmental monitoring stands in stark contrast to the prevalent model. It requires transparency in the calculation of environmental footprints, where methodologies and assumptions are fully auditable and reproducible.

Transparency in environmental data is crucial to building trust among all stakeholders, from farmers to consumers, ensuring that environmental claims are credible and verifiable. When data and methodologies are open and transparent, they can be scrutinized, debated and improved upon, leading to more accurate and reproducible results. It also enables the identification and correction of errors in data collection and analysis.

Open datasets and models utilized at source also ensure that farmers retain ownership of their data and control over how it is used. Even if farmers have a limited understanding of the complex data generated, owning it ensures they are not left out of the decision-making process. This ownership also means they can directly benefit from their data, whether through participation in carbon markets, receiving payments for ecosystem services, or optimizing their farming practices.

In other words, tying data agency and ownership to direct tangible incentives (e.g. cash) for farmers is not just the right thing to do from a climate justice perspective, but also is crucial for these value chains to actually adapt and thrive through climate change.

For the buyer, a reporting platform built on this open-data approach significantly lowers the audit costs and instills significantly more confidence in the quality of the underlying sustainability claims and progress. It reduces risks for the brands around misleading claims and ensures traceability and consent to the farms. Most importantly, this creates a clear path to action, driving interventions at the supply base, and moving the industry past a seemingly never-ending measurement stage.

This is not an unattainable, utopian future – Epoch already does this for tens of thousands of smallholders today using open and transparent industry-led tools like Cool Farm Tool and its own white-papered methodologies, to allocate farmer incentives tied to improvement in sustainability metrics.

The path forward: shifting the system from burden to reward

We are at an inflection point. We believe that there is an unparalleled opportunity to utilize this moment to drive more power, income, and agency to smallholder farmers.

There are burgeoning innovations (both technical and business model) within the MRV space that promise a brighter future. The emergence of ever-improving datasets like Forest Data Partnership’s commodity maps, foundational models by Earth Genome and Clay, continuous land cover maps like Dynamic World by Google and World Resources Institute, and forest carbon data by cTrees promise high quality remote analytics within reach without proprietary, opaque and costly commercial solutions.

Innovative business models integrate the latest in fintech to not only help corporations drive return on investment (ROI) through their net-zero journeys but also provide tangible economic benefits to their suppliers. They rely on data sharing rather than guarding as a key driver for their growth. They attach monetization not to the production and “sale” of the data, but to the actions and incentives driven through them.

Imagine a future where an open-data approach is the norm. A future in which 90% of the spend on sustainability initiatives is not on measurement, but on action. In this world, the 500 million smallholders globally are properly incentivized to adopt low-carbon intensive methods that not only reduce emissions but also make their farms more resilient to climate stresses and shocks while lifting them out of poverty.

Businesses massively lower the litigation risk from greenwashing and become compliant with minimal costs and become catalysts to drive climate action. Most importantly, the environment benefits from agriculture that respects and preserves biodiversity and ecological balance.

Conclusion

As we navigate the complexities of global supply chains and environmental regulations, we must foster an inclusive approach that empowers every stakeholder, especially those in the Global South. By adopting and supporting MRV systems with an open-data approach, we can ensure that the smallholder farmers, who are often the backbone of their economies, are not left behind in our journey to a more sustainable future.

In doing so, we not only uphold our environmental and ethical standards but also bring equity as a crucial part of this transformation.