Brazil is frequently praised as the most progressive country in the world when it comes to adopting biological crop solutions, thanks in no small part to its regulatory framework that enables speedy deployment of products to growers.

Developing said biologicals in Brazil is another story though, says Fernando Sousa, marketing and biologicals manager at Uby Agro subsidiary Vitales.

“Although the biological segment here in Brazil is well developed, the research capabilities that we have in place right now are medium to small,” he tells AgFunderNews.

When Sousa traveled to Sacramento and met with biotech company Ginkgo Bioworks — a company known for helping others bring biological products to market quickly — he found a completely different story.

“Ginkgo’s expertise in fermentation and formulation, with teams working collaboratively under the same roof, will speed up the development of economically viable product concepts,” he says.

Just recently, the two companies announced a new partnership aimed at accelerating development and launch of two new biocontrol products that target soybean diseases in Brazil.

Partnerships in Brazil ‘take a long time’

Ag research firm Kynetic estimates that biocontrol products in Brazil have an average growth rate of 35% per year for the past five seasons and now constitute 4.2% of the entire crop protection market.

Thanks to this, Brazilian producers are “really engaged” in using biologicals for crops largely because of the region’s climate,” says Sousa. Climate, which impacts the length of the growing season, is also a factor.

“We don’t have snow in the winter. In fact, it’s pretty hot, so the cycle of bugs is not interrupted by any major environmental effects. That’s why we use a lot of crop protection products.”

Sousa estimates that Brazilian producers use around 1.4 million tons of crop protection products each year, holding roughly 20% of the crop protection market worldwide.

At the same time, producers are dealing with “decreasing efficiency of a good proportion of those products,” he says. “Sixty percent of total producers [in Brazil] are already using biologicals. We expect, in the next 10 to 12 years, [for Brazil] to have at least 10% of the total crop potential market using biological control products.”

Given this demand, not to mention a regulatory environment that’s famous worldwide for its progress in biologicals, Vitales needed a way to produce products faster.

“The partnership between companies and universities in Brazil takes a long time, and you don’t have full control of [the deliverables],” explains Sousa.

Ginkgo’s capabilities allow companies to rapidly discover microbes and quickly pass those microbes through a series of assays to determine which ones have the potential to solve a customer’s given problem.

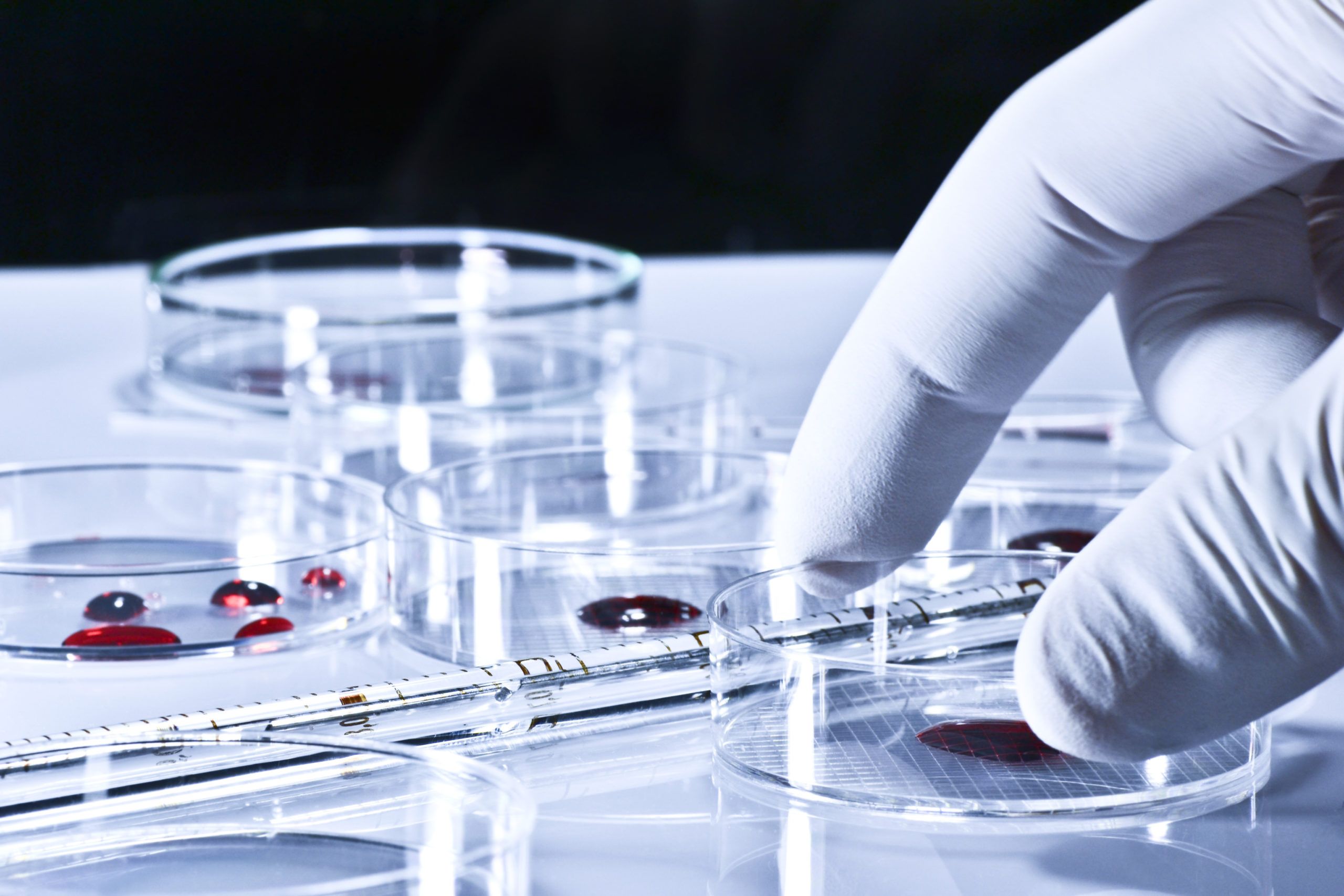

From petri dishes to 375,000 strains

“From Fernando’s perspective, he was looking for a company or a partner who can develop products quickly,” says Brennan Duty, senior director of business development at Ginkgo Bioworks.

In particular, Ginkgo has a product called Head Start, which includes “validated leads.”

“These are strains that we had in our 375,000-plus strain bank that we had already screened for activity against the diseases that were interesting to Fernando and his organization.”

Around half of the 375,000 strains are already sequenced and come from agriculturally relevant sources, mostly from the US but also from a few other parts of the world, says Duty.

The Vitales-Ginkgo partnership is specifically targeting soybean diseases in Brazil, including Soybean Sudden Death Syndrome (SDS) and target spot, caused by the pathogens Fusarium virguliforme and Corynespora cassiicola, respectively.

Ginkgo is “a perfect fit” for a company like Vitales, which doesn’t want to invest millions of dollars in developing laboratory space and hiring PhDs, he adds.

“We exist to provide our expertise to customers who are operating in the space. So at a high level, that’s what brought us two together.”

“[In Brazil] We take petri dishes, thousands of them, and start doing the screening between the microorganisms and the target we want to control. This takes a lot of time,” says Sousa.

“Once you go to Ginkgo, you find a machine two times the size of a room that can do the screening fully automatically with more than 1,000 different microorganisms.”

He adds that Ginkgo’s expertise in formulation will also enable development of seed treatments and foliar applications that can be specifically tailored to the Brazilian agriculture industry.

“Those capabilities, together with the human resources that Gingko has, reduce the timeline, the investment investment and risk.”