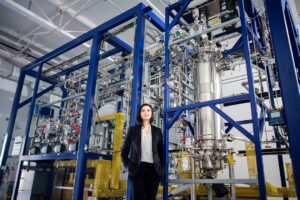

Editor’s Note: Sara Menker is CEO of ag data and analytics software Gro Intelligence. Prior to founding Gro, Sara was a vice president in Morgan Stanley’s commodities group. Gro’s software automatically harvests disparate data, transforms it into knowledge, and uses machine learning to make predictions offering users analytical tools, intuitive agriculture-centric visualizations, and live dashboards.

Each and every month, millions of actors across the global agricultural sector wait with bated breath for the latest crop yield forecasts from the World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE). WASDE is produced by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) and is the global benchmark for assessing crop yields, before and after harvest, in the US and globally. Yet its methods are damagingly opaque and are causing unnecessary amounts of volatility and instability across global agriculture.

Last week we released a report calling for changes to the WASDE process to make it more transparent and more frequent. We believe WASDE is ripe for innovation – it is a system that has barely changed since it was formally established 40 years ago, and USDA lags behind other comparable bodies in terms of transparency and the evolution of its methods.

Seth Meyer, the chairman of the World Agricultural Outlook Board, which produces the WASDE, has disagreed that reform is needed, saying “Satellite imagery is not a replacement for farmer surveys or on-the-ground sampling.” His reply avoided addressing the main point, though, which was that the USDA’s process is unnecessarily slow and opaque. The report’s monthly timetable began in the 1970s and hasn’t changed since. Why does the USDA maintain a cloak of secrecy around the exact methods by which the WASDE is produced each month and the weights given to the different pieces of information used for the estimates? By comparison, and without any drama, the US Energy Information Administration produces a complex report on its industry’s status, and it does so every week.

The USDA has long been the undisputed public source for information on global crop supply and demand, and WASDE has pretty accurate numbers most of the time. Year round, a highly disciplined army of analysts fans out over the globe’s crop areas and builds a balance sheet. This is where the term ‘bean counter’ comes from.

But now, largely due to the USDA’s, USGS’, and NASA’s pioneering efforts over the past five decades, orbital cameras and other sensors can remotely discern numerous relevant attributes of crops. They measure moisture, temperature, chlorophyll activity, evaporation, transpiration, precipitation, and visual greenness in order to quantify crop health on a daily basis. With those streams of data, a small group of experts armed with sufficient computing power can produce a daily forecast that is objectively reproducible and converges sooner to a final number than the USDA’s traditional process. Gro Intelligence’s corn yield model, which we released for free and publicly in 2017, demonstrates all of this. We were able to consistently predict USDA’s yield numbers two weeks ahead of time on a monthly basis, and the final US corn yield six weeks ahead of USDA in November 2017.

Most advanced yield models update daily. The USDA doesn’t let the public know what its models say until the monthly WASDE release dates, and even then it doesn’t explain how they got to those numbers. For instance, it certainly has numbers for 11-14th May, but the public cannot see the new information until the next report on 12 June. The costs of this arbitrary delay can only begin to be expressed in terms of money.

As an example, during the US drought of 2012, prices for all agricultural commodities skyrocketed, causing significant suffering in many parts of the world. While the USDA’s (and others’) satellite models secretly watched the crop deteriorate on a daily basis, the industry was forced to speculate on the severity of the situation. Delayed information flow meant that companies and governments particularly, reacted slowly, exacerbating the crisis’ painful effects.

The best possible crop model undoubtedly synthesizes surveys, sampling, and satellites. The USDA has surely worked out a great way to combine the three as WASDE presents pretty accurate numbers most of the time. But we don’t know what that way is, because the data and methods are shrouded in unnecessary mystery. The USDA needs to explain how the WASDE numbers get calculated every time they get released. There is a large community of crop modelers vigorously debating the pros and cons of different forecasts, and the USDA should join in on this conversation. After all, education and outreach are both parts of the USDA’s mission. Let’s drag WASDE into the 21st century and use USDA’s methods and knowledge to help people everywhere understand their agricultural prospects sooner.