What happens when you mix decades of mining experience with entomology and a desire to improve the planet? For brothers Ramon and Ricky Atayde, that combination produced ARC Ento Tech Ltd, a company turning municipal solid waste (MSW) into animal feeds, fertilizers and a reductant that could replace coking coal.

MSW, aka trash, is a massive problem worldwide for rural and urban settings alike. The average American wastes around 4.9 pounds of trash per day. In Australia, where ARC Ento Tech is headquartered, well over half of the 67 million tons of MSW winds up in the landfill.

Developing countries grapple with population growth and rapid urbanization that are causing major increases in the amount of MSW consumers produce; municipalities struggle to effectively manage their mounting trash problems.

The global reach of the MSW problem is key factor in ARC Ento Tech’s underlying goal, which is to turn waste into valuable resources from anywhere in the world.

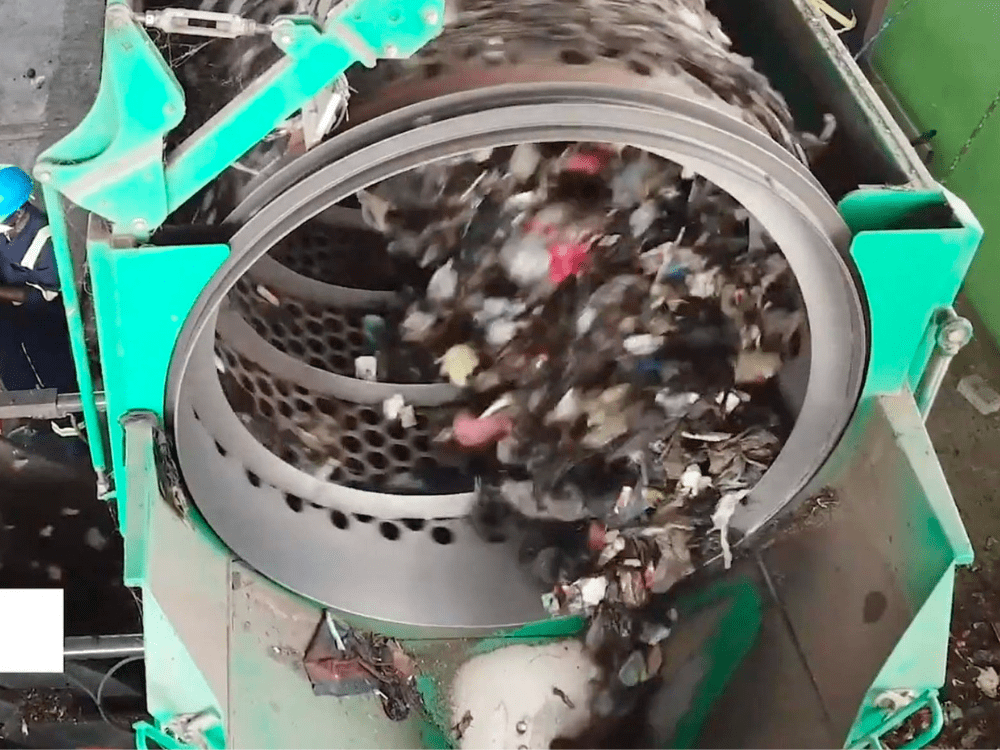

The company’s system employs the black soldier fly for consuming organic waste (e.g., food scraps) into larvae that can be used for feed and fertilizer. Indigestible organic waste (wood, rubber, paper) and plastic leftover undergoes a patent-pending technical process that turns it into a high-carbon reductant for industrial use.

Most companies using black soldier flies to process waste bring the waste to a single plant. ARC Ento Tech flips that model on its head.

“Rather than going to a centralized plant, we decentralize the system and put plants at the landfill,” Ramon Atayde, the company’s chairman and managing director, tells AFN. “That way, we don’t spend on logistics, which is the biggest cost component for most businesses today.”

The company is currently fundraising in order to establish its first six plants then expand across Australia and internationally.

Atayde (RA) is a veteran of the mining industry. Read on for how his background informs his work today and why he believes decentralized systems are the key to achieving sustainable processes at scale.

AFN: What led you to insects?

RA: My brother [Ricky Atayde] is an entomologist — he’s been working on insects for over 15 years, growing them for the pet food industry. I’ve been in the mining industry for 36 years.

About five years ago, [my brother] said, we should look at the pet industry because the live insect trade is about $17 million dollars in Australia, and there are only two major players. We saw an opportunity for a third player. Even if we only got 10% market share, it’s reasonably decent.

But we didn’t want to become “the pet food magnates.” We wanted to do something that actually had an impact in the world.

My brother felt the black soldier fly was the one insect that could make a change; he was growing them. The technology around black soldier flies was really only developed about 10 years ago, so it’s an emerging industry.

The world has already identified the black soldier fly as a potential [solution] to solve the organic waste problem and provide us with a sustainable protein source as a substitute for fishmeal, which is one of the primary protein components in livestock feeds. It comes from wild-caught fish stocks, and because of population growth, it cannot sustain our consumption.

In the past fishmeal was made out of bycatch. Today, they’re using edible fish that other countries could actually consume, so it’s no longer sustainable.

AFN: What have you done differently from other companies using black solider flies?

RA: Around the world, the black soldier fly industry uses very conventional, antiquated models. They spend a lot of money on one big factory and transport the food to the insects in those factories.

That’s expensive. These companies aren’t selling insect protein at a high profit rate, they’re were selling just to break even.

Secondly, everyone still used the standard tray batch system. We had to find a way to change that.

I was able to bring up my background in scale. In mining, we don’t talk micro. Everything is big. I don’t see things as a one-ton-per-day industry. I see things from the perspective of a million tons a year.

So I could find the equipment, methods and processes, borrow from industries I’d been exposed to and apply it to this new method we were developing to see whether nature accepted it. We don’t want to change the nature of the fly. We want to exploit its physical ability and instincts to eat waste and survive.

That’s how we developed this continuous process and that’s our patent-pending technology.

AFN: What about plastic waste?

RA: In that red bin, 80% is plastic waste, unfortunately. We didn’t want to make more furniture. We didn’t want to make more construction materials, because those are retail focused solutions.

We leveraged my background as a mining engineer, and I’ve also done a lot in steel and in metallurgy. And one of the key components of our industry is a source of carbon, which we get from coal.

So we produce a synthetic coal from that plastic waste.

AFN: What major problem does the system solve?

RA: In order to overcome that issue of logistics — bringing food to the flies — we had understand where most of our waste goes.

Rather than going to a centralized plant, we decentralize the system and put the plants at the landfill. We don’t spend on logistics because the waste is being picked up anyway. And that’s the same situation around the world.

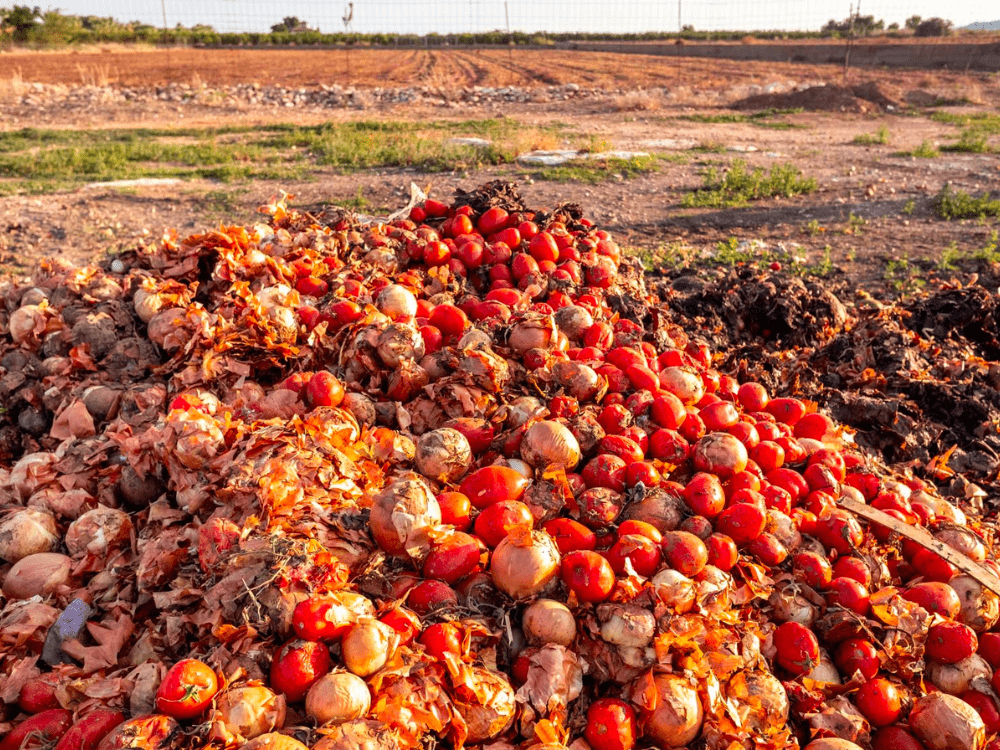

We researched and found that our red bin [garbage] waste is food waste on average. It’s similar, probably worse, in the developing world because they don’t have the storage and handling facilities. So we put the processing plants close to the waste.

AFN: Why the black soldier fly

RA: Compare it to blowflies and houseflies; those are filth flies. The difference is that that filth flies have to eat every day, so they are attracted to contaminated waste. That’s how they pick up pathogens and spread them around.

Nature gave the black soldier fly adult a very challenging physical limitation: it’s mouth doesn’t work anymore; it can’t eat. And it only has 14 days to live. Their sole purpose is to breed, lay eggs and die.

It’s their larvae that’s valuable. Their larvae have a different physical advantage over any other fly, so it’s the perfect eating machine. We could call it a “waste processing system.” And the protein content is high.

But more importantly is the digestibility. Certain are high in crude protein contents. Not all that crude protein is digestible.

For example, when we use fishmeal in poultry feeds, the chicken consumes only 40 to 45% of the protein content. The rest goes into its manure, but it’s a waste of that resource.

The insect protein, on the other hand, is much more digestible, so the protein content might be less but we’re talking about 75 to 80% digestibility.

AFN: Has this work changed your idea of what is and isn’t waste?

RA: We don’t see waste the way we used to. We now see it as a resource. It might not become a new plastic bottle or that particular nutrient we recovered. A rotten apple can’t be converted into fresh apple. But we can use the waste in some way to deliver us back that fresh apple.

So now we’re not dependent on primary natural resources. We actually have a secondary source of raw material or commodities. We’re not going out to nature and continually taking from it. We’ve got everything we need from everything we’ve consumed. That’s the circularity of that concept.

AFN: Describe a major challenge you’ve faced building the system/company.

RA: Our challenge was make it affordable. We can’t go to the market and say, “this is the way to go but you have to pay more.”

We had to find a way to ensure that the business model was dependent on the product, not the front end. Many times people make the profits from the gate fees or the processing fees. They forget about making sure that this works on the back end. When that happens it eliminates countries who don’t pay upfront because they can’t afford it.

We’ve developed a system that allows us to build a self-sustaining business, and our model works anywhere: Australia, the US, Europe, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Africa. The model works because it brings food prices down.

It also contributes to a healthy agricultural industry because instead of promoting chemical fertilizers for example, we are much more involved with soil health because we we provide a good carbon content. We provide the right micronutrients from our source rather than just the chemical nitrogen-phosphorus-potassium blend.

Now we have Macquarie University, Western Sydney University, Sydney University and even the University of Newcastle and recently because of the introduction evoke and within all that South Queensland University are very keen to work with us because we went completely off track.

Most black soldier fly companies stay on the safe side and don’t do contaminated waste, only the clean agricultural waste. We started with the worst because if we fix the worst, everything else is easy.