Editor’s Note: Noel Dickover is the director of PeaceTech Data Networks at the PeaceTech Lab. The Lab was created by US Institute of Peace to advance the institute’s work at the intersection of technology, media and data with the aiming of reducing violent conflict around the world.

Dickover heads up the recently-launched Open Situation Room eXchange project, which is a collaboration and data sharing platform for peacebuilders in conflict zones. Here he explains how agriculture big data tools, particularly those tracking weather, can help.

——————

A recent NASA study found that the drought that began in 1998 in the eastern Mediterranean Levant region, including conflict-affected countries such as Cyprus, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, and Turkey, was the worst drought in over 900 years.

In fact, some studies have explored the connections between climate change, migration, and social instability.

Researchers have demonstrated that an extreme drought in Syria between 2006 and 2009 was closely linked to the emergence of the violent uprising that began in 2011, escalating the ‘Arab Spring’ movement across the region. A combination of “poor governance and unsustainable agricultural and environmental policies” led to a catalytic effect that contributed to unrest.

The researchers found that the drought exacerbated existing water and agricultural insecurity and caused massive agricultural failures and livestock mortality — the consequence of which was over 1.5 million people migrating from rural areas to urban centers. This, with other factors, catalyzed into the Arab Spring.

Climate change is causing significant shifts in weather patterns. These weather shifts are contributing to desertification in some of the world’s most violent conflict areas such as Darfur, and this desertification is becoming a driver of conflict.

Since 2003, an ongoing conflict between various violent nomadic militias and government forces has led to over 200,000 deaths and 2.5 million displaced people. While it’s primarily a human-centered conflict, deserts have been spreading south in the Sudan for the past four decades. This has led to a 12% loss of forest cover over the last 15 years. Simultaneously, livestock herds have grown from just over 25 million to 125 million. The stress of desertification and “the irregular but marked decline in rainfall,” has pushed the UN to proclaim that we are “unlikely to see a lasting peace unless widespread and rapidly accelerating environmental degradation is urgently addressed.”

The January 2014, the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) report, Desertification: The Invisible Frontline, stated that more than 1.5 billion people depend on land that’s degrading, and 74 percent of them are poor.

It is in this context that the PeaceTech Lab started investigating climate change-related data sources that could help detect early warning signs of social unrest and conflict. And a new movement is now underway in the peacebuilding sector to start exploring this in conflict zones.

Data can come from the event reports of protests and violent incidents, conversations about those events on social media, and from a variety of other structured and unstructured sources. By aggregating disparate information sources, the hope is that we can find better insights on tensions arising from inter-communal violence, ethnic and religious tensions, poor governance or gender issues. The PeaceTech Lab’s Open Situation Room Exchange provides an early attempt to use this information to provide a baseline view of conflict across the globe.

We are also starting to look at the data that’s being collected by agriculture technology companies, particularly regarding weather. There are several startups and businesses collecting, analyzing, and monitoring weather patterns to provide actionable situational awareness information to a variety of stakeholders, including farmers, commercial growers, and commodity traders.

It is very likely that this same data has implications for peace builders too.

Weather data layered onto geospatial technology and data analytics can be a key decision support tool for local advocates for peace, especially when combined with an SMS, mobile, and email alert system. The results of this can be fed into a multi-platform digital storytelling approach to advocate change in governance and agriculture policies.

One example is aWhere Inc, a Colorado-based company that has such fine resolution agronomic weather data that it can show “pocket droughts”; areas where relatively small pockets of land are experiencing agronomically impactful drought. These spatially-smaller yet intense droughts can lead to competition over scarce resources and can change migration patterns. In some geographies, this contributes to population growth in megacities that are already experiencing significant unemployment, or may render populations more vulnerable to extremist ideas.

aWhere’s dataset is derived through a global-scale agronomic modeling effort with immense processing capacity that collects and creates over a billion points of data every day to construct daily agro-met data sets for every ‘grid’ of around 9 km in size. With such localized data, we can get unprecedented visibility and insight into hyper-local contexts across the planet.

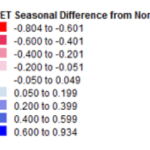

By comparing current rainfall (P for precipitation) as a ratio of the evaporative demand of the environment (termed ‘Potential Evapotranspiration’ – PET) with the last 5-10 year average of the same P/PET ratio, aWhere can provide maps identifying droughts — specifically pocket droughts — in real-time that may have implications for conflict.

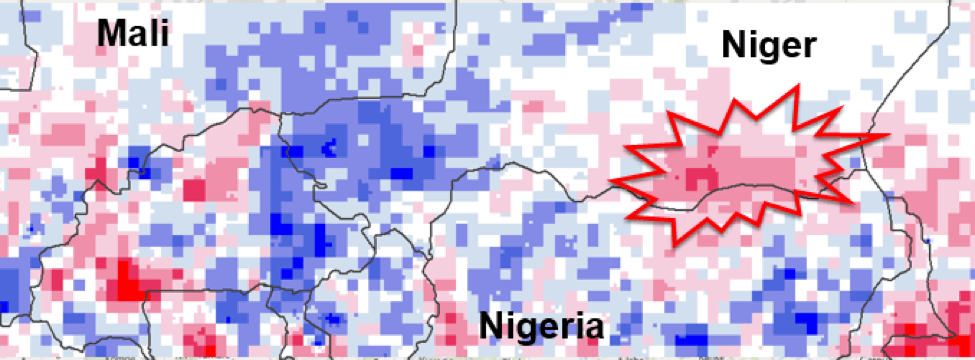

Here’s how weather could have predicted conflict in Niger in 2015. The area in red highlighted below, centered around Zinder, Niger, typically has an agro-climate type that can produce sorghum, but this was not the case in 2015. This area received far less than normal rainfall and, as is typical in ‘dry’ years, the temperatures were warmer and the humidity lower than normal compounding the impact of too little rainfall on local agricultural production.

In this map covering Eastern Mali, Burkina Faso, southern Niger, and northern Nigeria, the gradient between the blue (wetter and lower PET in 2016) and red (drier and higher PET in 2016) depicts P/PET for June 1 – August 14, 2015, compared to the last 5 years of ‘normal’ conditions. Displaced persons were observed throughout the area south of the highlighted red area above. This led to negative impacts, including Boko Haram activity in the region.

Bearing in the mind the potential for aWhere to use weather data in this way, the PeaceTech Lab is looking to integrate aWhere’s weather data and agronomic models with its existing indicators of conflict. Through this integration, we hope we can receive important early warning signals about the potential for new migrations resulting from food insecurity and competition over scarce resources and send the information to peace builders in the region.

In the not too distant future, the PeaceTech Lab will be able to marshal data resources from leading data providers like aWhere to transform the way the world thinks about, and responds to, emerging drivers of conflict.

Have news, tips, or want to write a guest commentary? Email [email protected]