Editor’s note: Gustavo Mamao is head of international business development at IdeeLab, Brazilian foremost CDMO in ag biologicals.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent those of AgFunderNews.

Biological inputs are often highlighted as essential tools for advancing sustainable agriculture. They improve soil health, optimize nutrient efficiency, and reduce chemical dependence through integrated pest and fertilization practices. Yet a critical question remains: how can these environmental benefits translate into a clear business case for growers?

Ag biologicals often start the race in the wrong lane: they are seen merely as replacements for existing chemical products. As such they wind up competing in a space defined by efficacy and cost, rather than by the broader value they create. In reality, biologicals deliver far more than the narrow problem–solution approach that has long characterized the chemical paradigm.

Biological manufacturers can fall into this trap, positioning their products as substitutes instead of enablers of system transformation. By contrast, outsiders—startups or companies created with a better biological mindset fit—may be better positioned to recognize the full potential of biologicals and to design business models that extend beyond simply selling agricultural inputs.

Currently, most investors—particularly in venture capital—still classify ag biologicals within the broader agtech basket. Unfortunately, that basket is not faring well. Funding for agtech and foodtech has fallen to its lowest historical levels, making it more difficult for ag biological-based new ventures to attract growth capital.

For these reasons, it’s time to elevate the conversation and frame ag biologicals within more suitable contexts.

The regenerative agriculture movement

Regenerative Agriculture has gained momentum for its potential to revive traditional farming wisdom while serving as both a climate adaptation and climate mitigation strategy, making farms more resilient to stress while helping agriculture play a role in slowing climate change.

Although the definition of regenerative agriculture is blurry, most frameworks converge on a common set of principles and practices: minimizing soil disturbance (i.e., minimal or no tillage), increasing organic inputs, maintaining continuous soil cover, integrating livestock and plants, and diversifying crops. These practices aim to restore soil health, enhance biodiversity, and rebuild ecosystem functions.

While organic certification has successfully built a strong consumer market, it also enforces stricter input standards—including for biologicals—which has limited scalability and slow adoption at larger farm levels. Today, less than 1% of U.S. agricultural land is “certified organic.”

By contrast, regenerative agriculture offers more flexibility. It encourages farmers to combine practices in ways that fit their local conditions. According to USDA data, about 4.7% of U.S. cropland was planted with cover crops in 2022 (up 17% since 2017), while roughly 27.5% was managed under no-till practices. It is a more systemic approach, and it might be said that the best outcomes emerge over time. Once a transition phase is completed, it can lead to improved input efficiency and cost savings.

The synergy between regenerative practices and ag biologicals is particularly promising. The same practices that increase soil organic matter—such as cover cropping or livestock integration—also create a richer microbial environment that amplifies the effectiveness of biological inputs. For example, the combined use of biostimulants with organic matter additions can reduce dependency on synthetic fertilizers, particularly potassium (K) and nitrogen (N) sources, while maintaining or improving yields. Some ag biological manufacturers have been claiming 25% reductions in nitrogen application across the board. The open question is: how much additional N savings could result from deeper adoption of regenerative practices?

Beyond input efficiency, Regenerative Agriculture is also beginning to generate market differentiation, much like organic agriculture once did. Emerging brands are already capturing part of this value. For instance, Alec’s Ice Cream recently raised $11 million in a Series A round, positioning its regenerative sourcing as a core element of its identity.

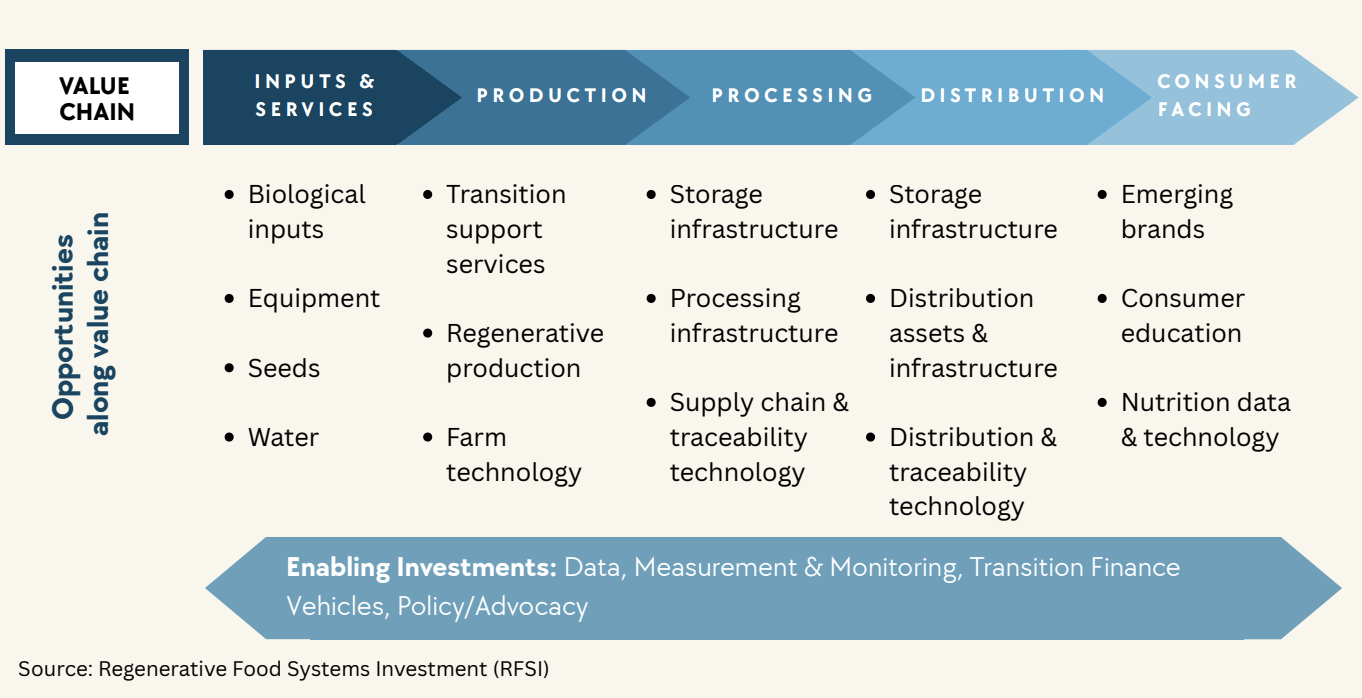

When viewed across the full value chain, regenerative agriculture—encompassing biological inputs among other practices—can simultaneously lower long-term production costs and open premium opportunities for brands able to educate consumers and communicate the regenerative story effectively.

As the movement matures, a new question arises: how can this environmental and agronomic progress translate into direct financial returns for farmers?

Turning ecosystem services into farm revenue

A new dimension of the regenerative agriculture business case lies in compensating farmers for the ecosystem services they provide. Beyond productivity gains and cost reductions, growers can now access additional revenue streams by contributing to measurable environmental outcomes. Among these, carbon sequestration and greenhouse gas emission reductions are currently the most recognized and financially structured mechanisms.

Several ag biological companies are positioning themselves at this intersection—where biological innovation meets climate finance. Some operate both businesses in parallel, while others are building integrated models that link their biological inputs directly to verified carbon or sustainability outcomes.

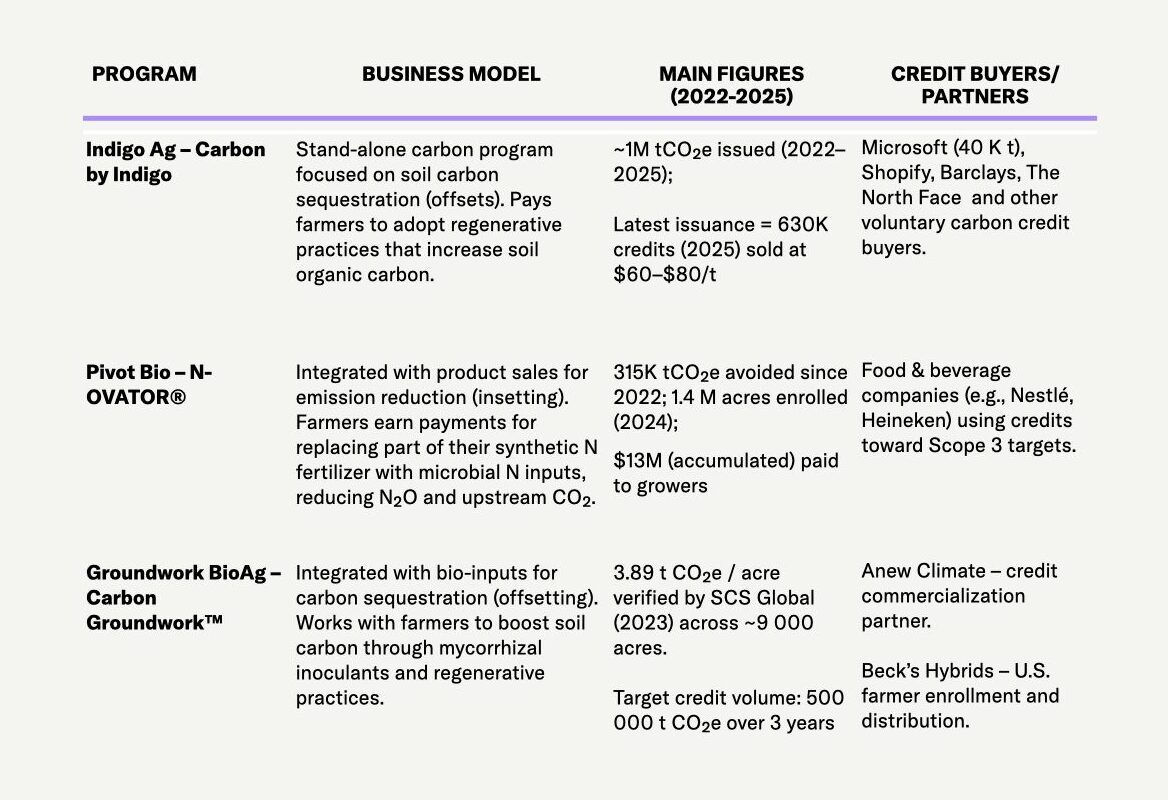

From the growing landscape of ag biological manufacturers, three cases illustrate how the sector is evolving to connect biological performance with environmental monetization:

As shown in the table on Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) in U.S. Agriculture, most of these programs and certifications are still in their early stages. Yet, they have the potential to grow significantly over the next few years, driven by both “insetting” initiatives (emissions avoided within a company’s own supply chain, such as in food and agriculture) and “offsetting” mechanisms (emissions compensated outside of it).

Much of this expansion is fueled by private-sector climate commitments to decarbonize supply chains. Farmers’ payments are in the range of 70% of the net revenue of those programs.

The case of Groundwork BioAg, with its recent announcements, has generated intense debate about the technical parameters of carbon sequestration payments versus company claims.

Was 3.8 tCO₂e per acre a realistic figure—or overly optimistic? How should this value vary across different soil types and management conditions? How do we account for additionality among farmers who were already using biological inputs, and for permanence when practices change or fields are tilled?

While these questions are critical, the Groundwork example is also inspiring: it demonstrates the potential for soil-based carbon credits generated through the use of ag biologicals—being an alternative for the dominance of forestry offsets. Expanding on this idea, there is an enormous opportunity to make soil-based carbon models more accessible and scalable—reducing the friction that currently prevents many farmers from participating in ag biological–linked carbon programs.

Looking ahead, the same model could extend beyond carbon. The use of ag biologicals also delivers other measurable ecosystem services—such as improved soil health, enhanced water retention, and increased biodiversity—particularly through the reduction of synthetic chemical use. These co-benefits could eventually become tradable environmental assets in their own right.

In parallel, clearer metrics for these positive environmental outcomes could attract impact investors, helping to fill the growing capital gap left by traditional venture capital in the ag biologicals space. By linking environmental performance to investable outcomes, the sector could unlock new forms of blended or catalytic finance aligned with regenerative agriculture goals.

The big lesson

By connecting biological innovation, regenerative agriculture practices, and financial recognition through mechanisms like carbon, as part of a broad range of ecosystem-service payments, the agricultural sector can move toward a model that is not only economically viable but also ecologically restorative.

In the coming years, as the ag biologicals market continues to expand, these sustainability frameworks—and the incentives behind them—will likely become more common and better structured. The goal should be clear: to ensure that the true environmental stewards—farmers implementing regenerative practices—are rewarded not just for their yield, but for the ecosystem value they create.