Michael Dean a the founding partner at AgFunder, the venture capital firm and parent company of AgFunderNews.

In late September of this year, AgFunder held a breakfast workshop in London for institutional and corporate LPs on the outlook for climate, agrifood, and deeptech investing in Europe. In preparing for the workshop, we leveraged our proprietary GAIA platform to extract data, yielding fascinating insights into the current state of VC investment in the region.

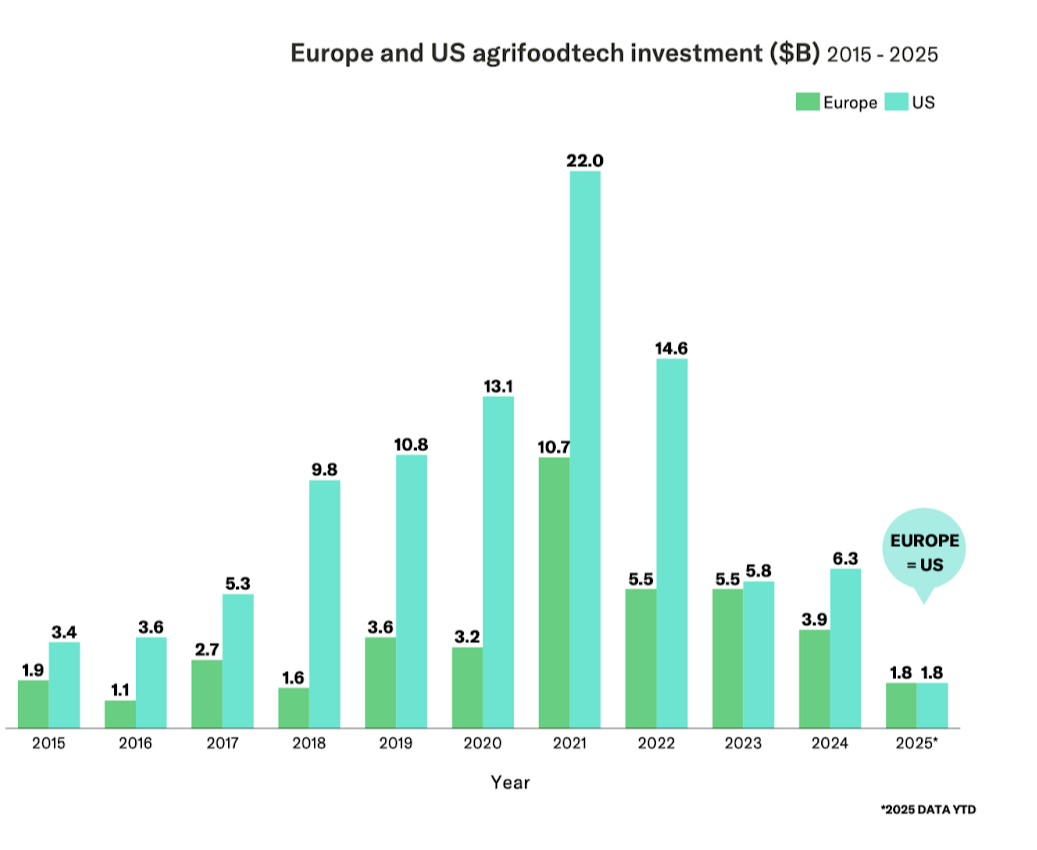

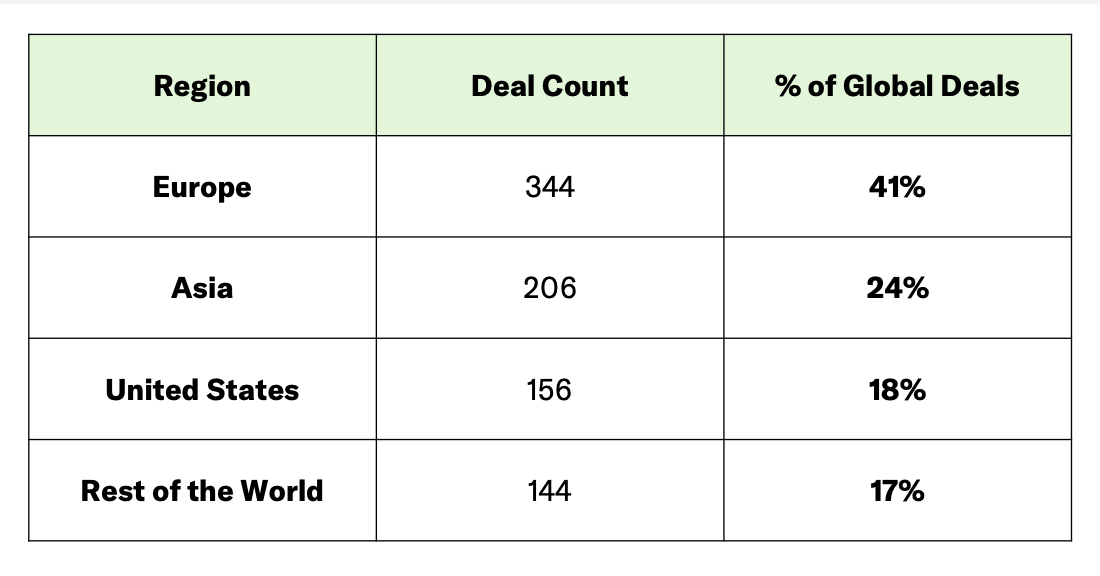

For the first time on record, Europe is on par with the United States for agrifoodtech investment. Furthermore, it now represents the world’s largest source of deal flow, accounting for 41% of all global agrifoodtech transactions in 2025 (as of the end of September). Five European markets (UK, Spain, Germany, France, and Italy) rank among the global top 10 for funding volume, together contributing $1.61 billion in capital so far this year.

On the surface, this paints a picture of a thriving ecosystem.

But Europe’s joint leadership position is not the result of a surge in investment, but rather a massive decline in US investment as it pivots aggressively into AI and defence, pulling generalist VC dollars away from sectors like food, biology, and climate.

Europe, with its slower-moving investor base and heavier institutional footprint, has simply fallen less quickly.

That nuance is important because the European Union now faces a crucial strategic question: whether to use this opportunity to build a globally competitive agrifoodtech and broader innovation economy, or to simply continue to fall behind.

The good news is that Europe has everything it needs for success: world-class science, global food and agriculture corporations, deep dry powder reserves, and a consumer base that rewards sustainability. But to unlock this potential, it needs to fix the regulatory, structural, and investment barriers that currently suppress high-risk, high-reward innovation, especially in deeptech and AI.

Europe has enormous financial firepower, holding around €415 billion ($482 billion) in deployable investment capital (dry powder), the highest level in history. But just €59 billion ($68.5 billion) of this (14%) is allocated to venture capital; an even smaller proportion flows into agrifood and biotech innovation.

Despite this, Europe accounts for nearly half of all agrifoodtech deals worldwide in 2025. This indicates depth, diversity, and entrepreneurial strength across the UK, Spain, Germany, France, Italy, and the Nordics.

Europe’s challenge is not innovation, it is deployment. If the EU can modernize regulation, reform investment allocation, and embrace global technology transfer, it has all the ingredients to lead the next generation of food and agricultural transformation. Europe already sets the international benchmark for sustainability standards and consumer trust. It has multinational food and ag corporations capable of validating and scaling cutting-edge technologies. And it has scientific institutions producing some of the most advanced biological and climate-tech research in the world.

The problem is that Europe’s regulatory environment slows everything down. From novel foods to gene editing to digital farm regulation and AI regulation, Europe’s approval pathways are among the slowest and most unpredictable in the world. This pushes founders to relocate manufacturing and commercialization overseas. It discourages global innovators from entering the EU market, and it delays climate-critical technologies for European food and agricultural operators. Most crucially, it will dramatically slow, or worse, block AI-enabled technologies from real-world deployment.

Europe’s AI gamble

Nowhere is this better illustrated than with the emerging impact of the European Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act).

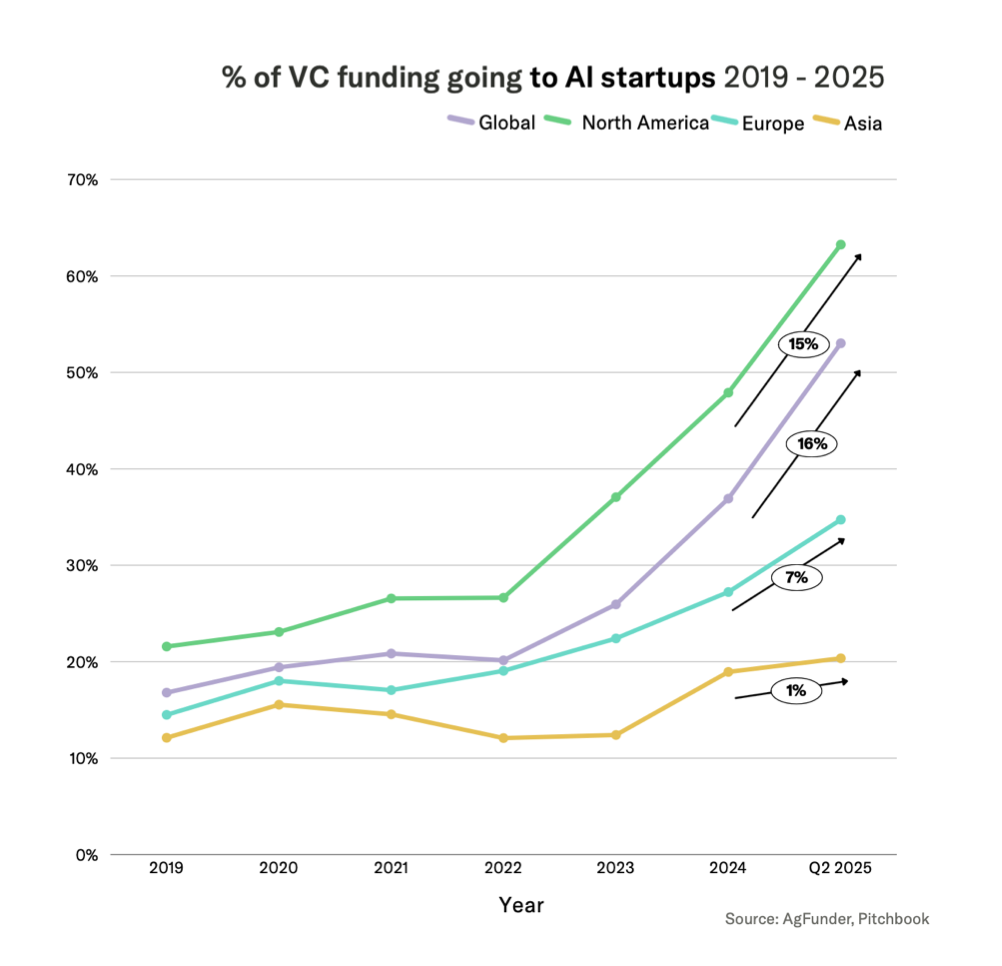

Data shows that AI is capturing global venture capital investment at levels never before seen, accounting for around 70% of US deal value in Q1 2025. European investment in AI is projected to reach 35% of total VC dollars this year, already badly lagging behind the US. But Europe’s ability to deploy sufficient capital to rapidly grow its AI innovation looks set to be materially hampered by regulatory overreach.

With the promulgation of the AI Act, Brussels has delivered the world’s first sweeping, legally binding regulation for AI. It’s a bold move that reflects Europe’s tradition of leading through governance, rather than scale. The intention is admirable. Europe wants to turn “trust” into a competitive advantage and position the EU as the global benchmark for safe and transparent AI. The idea is that a unified regulatory environment will give startups one clear rulebook. But in a race defined by speed, capital, and constant iteration, I think this approach is a strategic mistake.

Innovation happens in months, but this law operates in years. Startups will be forced to interpret vague “high-risk” definitions, undertake heavy compliance work before they ever reach product-market fit, and navigate ambiguity that even large corporates struggle to understand. The result is paralysis, not clarity. And while a European founder is working through their risk matrices, their American competitor is already in the market and their Chinese competitor is scaling through state-led industrial policy.

None of this diminishes the importance of trustworthy AI. But trust alone won’t secure Europe’s place as a global AI leader. Europe needs a regulatory model that protects its values while unleashing innovation, not smothering it. That requires a shift in strategy. Europe must match global competitors with serious investment billions and build public AI infrastructure so founders aren’t dependent on US cloud giants to train their models.

The AI Act itself needs refinement. It needs clearer, more practical definitions of “high risk,” a genuine fast track for startups to obtain the approvals they require, and exemptions that remove administrative barriers rather than offering minor fee reductions. And the Act’s regulatory sandboxes, currently little more than pilot programmes, must become true launchpads that are well-funded, free to access, and tied to automatic EU-wide approval for companies that prove compliance. The ambition behind the AI Act is admirable, but ambition without pragmatism becomes self-defeating.

Europe now faces a choice: build a framework that defends its principles while enabling its innovators to compete, or risk becoming a spectator to the world’s most important technological revolution.