Following 2019’s lettuce-linked E. coli outbreaks, which struck down hundreds of people with illness and led to several deaths, the US leafy greens industry has had a tough time.

Many consumers have turned away from the category, and the country’s Food & Drug Administration (FDA) recently said it’ll take enforcement action should outbreaks continue.

While these incidents have generally been linked to leafy greens grown outdoors, opportunity may be knocking for the expanding controlled environment agriculture (CEA) industry, which mainly works indoors.

“Our traditional approaches to food safety standards don’t take into account all of the questions that would […] for indoor production types,” Marni Karlin, executive director of the CEA Food Safety Coalition, tells AFN.

“Our goal is to help consumers, retailers, and regulators understand what indoor production is, and why it’s a value-added product. [We want] to identify those distinguishing factors around how our product is different and how it has different food safety risks and benefits.”

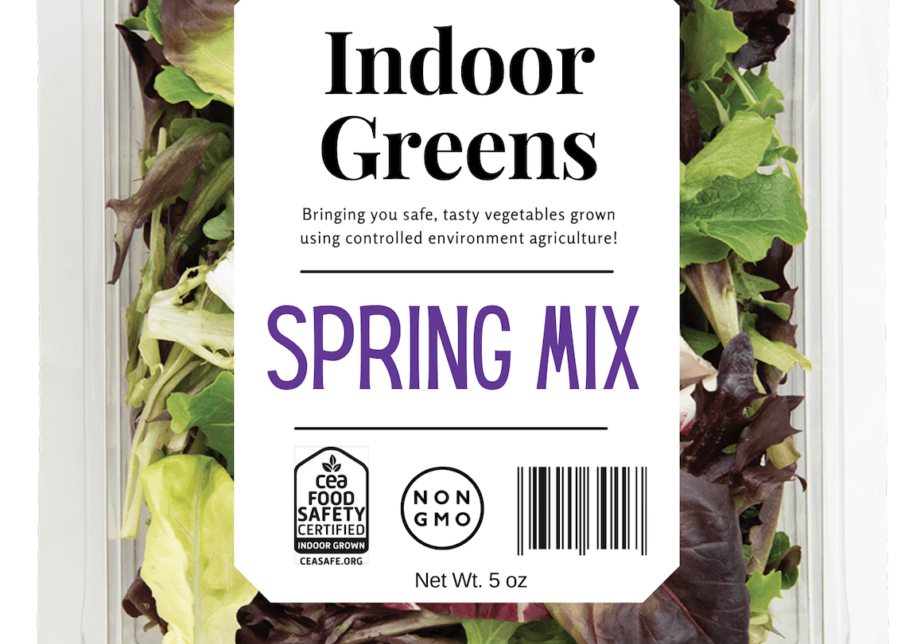

The Coalition recently unveiled what it describes as the first-ever food safety certification tailored specifically for indoor-grown leafy greens. Referred to as the CEA Leafy Greens Module (LGM), the new certification allows applicants to use a food-safe seal on their packaging to inform consumers about the safety protocols used to grow the greens.

The standards behind the LGM are backed by “science-based criteria” and build on the existing Global Food Safety Initiative food safety standard, according to the Coalition.

It began its mission in 2019 by reaching out to the FDA and the Centers for Disease Control on the nuts and bolts of indoor cultivation. This ultimately helped to convince the agencies that indoor-grown leafy greens could be omitted from the multitude of lettuce recalls initiated in the wake of the E. coli outbreaks.

Using existing field-based standards to assess safety in indoor farming operations “is a lot like putting a square peg into a round hole,” Karlin says.

Some of the key elements addressed in existing outdoor-based certifications touch on particular physical and microbial hazards from water, herbicide, and pesticide use – as well as impact from animals or animal byproducts – that are not implicated in indoor cultivation, the Coalition argues.

Creating standards for an emerging sector

Despite the fallout from the E. coli outbreaks, the indoor-grown leafy greens market appears to be on an upward trend as more players enter the space to meet consumer demand for safe, fresh, and locally-grown produce. The vertical farming produce market alone was valued at roughly $1 billion in 2019 and is expected to grow 26% annually between through 2027, according to data from Grand View Research.

Investors are pouring serious dollars into CEA, too – and that increasingly includes those active in the public markets. US high-tech greenhouse operator AppHarvest recently went public through a SPAC merger that valued the company at $1 billion, for example; while vertical farmer AeroFarms is completing its own $1.2 billion SPAC deal which will see it list on New York’s Nasdaq.

US crop genetics startup Benson Hill to go public in $2 billion SPAC deal – read more here

A third-party certification focused on food safety will offer some players in the space a chance to differentiate their products. It will also provide an additional educational platform to help consumers understand how indoor-grown produce differs from traditional field cultivation.

“[CEA] includes a whole variety of production methods like vertical, greenhouses, aeroponic, hydroponic, and aquaponic. So one of the big challenges was figuring out how to think about food safety in a way that let all of those growing practices be at the same table,” Karlin says.

The Coalition worked with multiple industry players as well as Global GAP North America, which develops industry standards and certification marks to highlight what it describes as “good agricultural practices.”

A number of indoor farming operations are already working through the Coalition’s certification requirements and have completed LGM training, according to Karlin – meaning that the new label could start appearing on shelves in the not-too-distant future.

But with the proliferation of food certification standards for everything from organic and carbon-neutral to ‘net-zero’ and ‘regeneratively farmed,’ it remains to be seen whether consumers have room on their metaphorical plates for yet another label.

“It’s a tough line to walk between really wanting to communicate to consumers what they are buying, and recognizing that there’s confusion and ‘label fatigue’ right now,” Karlin says.

“Where we came down on it was thinking that we have an opportunity to educate consumers about indoor farming and why it meets their needs for [food that is] pesticide-free, GMO-free, and more.”