Vonnie Estes is vice president of innovation at the International Fresh Produce Association and the host of the Fresh Takes on Tech podcast. The latest eight-episode season focuses on AI’s role in reshaping the global food system in a series of conversations with scientists, investors, and agtech leaders.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent those of AgFunderNews.

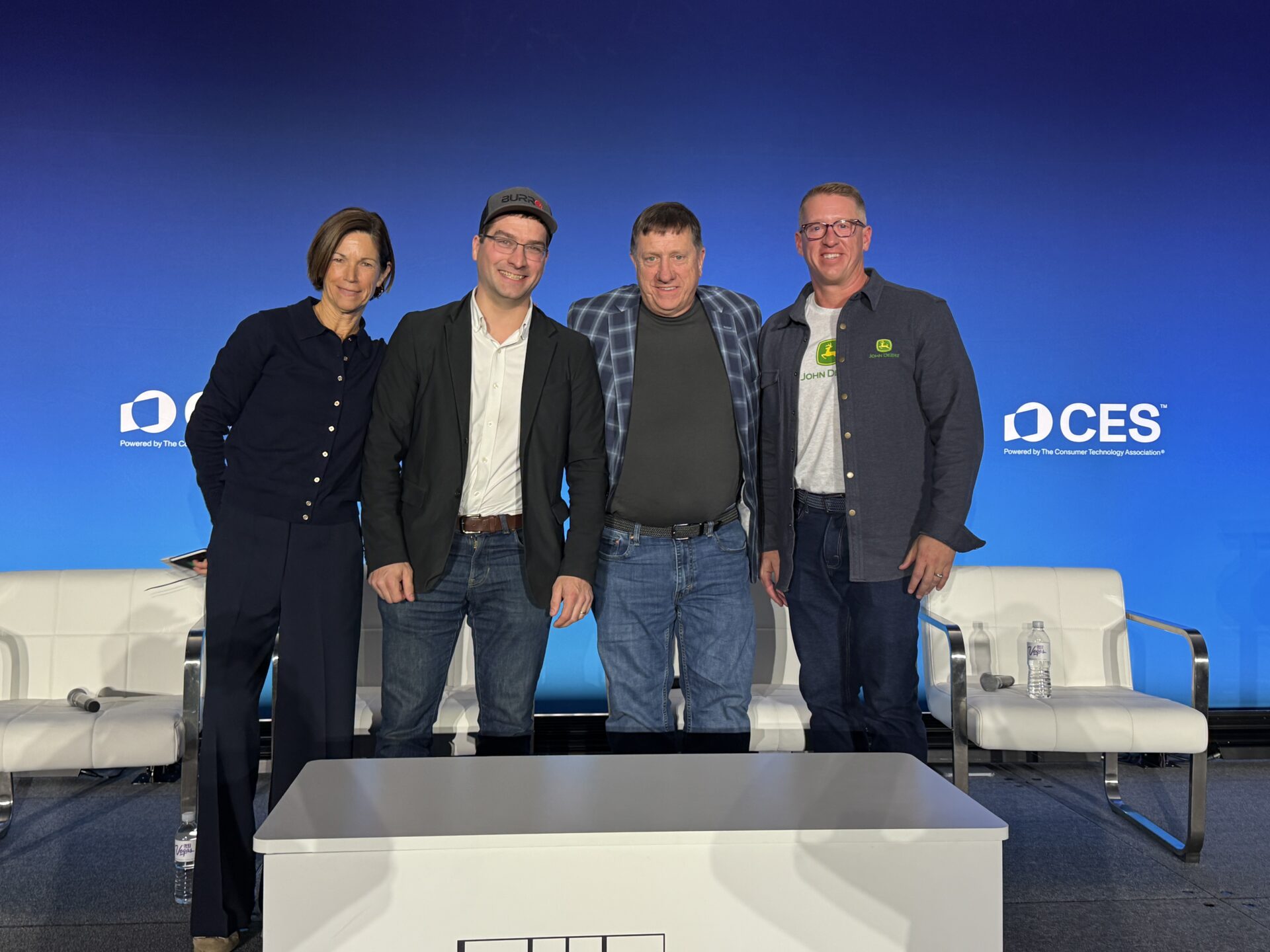

Every year at the Consumer Electronics Show (CES), agriculture shows up alongside autonomous vehicles and AI. And every year the same question comes up: Is this finally the year robots replace farm labor?

After moderating a panel on robotics and autonomy, the answer is still no. And that is exactly why robotics in the produce industry are finally starting to work.

What came through clearly in the discussion at CES is that the most successful robots are not trying to replace people; they are fixing the parts of produce operations that break most easily.

Produce is unforgiving. Harvest windows are short, quality drops fast. When labor does not show up on time, fruit stays in the field and value disappears.

That reality shaped much of the CES panel discussion.

Robotics that gain traction in produce tend to focus on timing and flow rather than full automation of complex biological tasks.

Selective automation beats universal robots

One of the strongest themes from the panel was that movement matters more than manipulation.

Harvest-assist platforms, autonomous carts in berries, and rolling systems in greenhouses do not replace workers. They remove walking, lifting, and waiting from the workday, making crews more productive, safer, and easier to retain.

Charlie Andersen, CEO of Burro, said, “The goal isn’t to replace people. It’s to take away the worst parts of the job so people can focus on the work that actually matters.”

That framing explains why agricultural operations are adopting these systems while more ambitious automation struggles.

Another important point from the panel was that automation in produce does not arrive all at once.

Agtonomy CEO and cofounder Tim Bucher reinforced the idea that adoption in specialty and permanent crops is incremental and has to fit into real operations.

“In specialty crops, automation doesn’t show up all at once. Growers adopt it step by step, where it fits into existing operations and actually solves a problem.”

That mindset helps explain why we are seeing progress first in specific places, such as high-value crops growing in structured environments with production systems designed with automation in mind.

For example, selective harvesting is gaining traction in greenhouse strawberries and tomatoes, where spacing, lighting, and crop flow can be engineered around machines. Outside of that, the ag industry has largely moved on from the idea of a universal harvest robot.

Why Deere is investing here

The investment perspective came through clearly from John Deere’s participation on the panel.

Ryan Krogh, global combine and FEE business manager at Deere, says his company sees autonomy as infrastructure. In other words, if you can make machines move safely and reliably, everything else builds on top of that foundation over time.

This platform approach aligns well with how produce operations actually adopt technology incrementally and across multiple tasks.

The panel also reinforced that some of the biggest robotics wins are not in the field at all. Packing-house automation for grading, sorting, packing, and palletizing is already widespread because it operates in controlled environments and directly addresses labor bottlenecks, quality consistency, and waste.

Meanwhile, precision weeding and spraying are also becoming more important as growers face increasing expectations around chemical use, worker exposure, and export requirements. Consistency and repeatability matter as much as raw efficiency.

The big takeaway? Solve real problems

For startups, the message from CES was clear: Solve real operational problems, design robots to work with people, and expect adoption to be crop-specific. Focus on reliability and integration, not flashy demos.

For investors, the signal is similar. The winners in produce robotics will not be the loudest; they will be the technologies that quietly become part of everyday operations.

Andersen’s closing statement summed it up: “The best robots are the ones growers stop talking about because they just work.”

The future of robotics in produce is not about eliminating labor. It is about making fragile systems more resilient.

The technologies gaining traction today help growers hit harvest windows, reduce waste, improve safety, and keep high-value specialty crops in production as labor markets tighten.

It may not look like science fiction. But from the field, the orchard, and the greenhouse, it looks like progress.