Europe’s share of global agri-foodtech venture capital is slim. But with growing pressure on food systems to produce more and more sustainably, Europe’s larger economies are ramping up efforts to cultivate a supportive startup scene.

Germany, which ranked fourth for agri-foodtech investment in 2018, pulling in $109 million across 21 deals, according to AgFunder and F&A Next’s recent report, is better known for its food tech successes than agtech — restaurant delivery group DeliveryHero and meal kit leader HelloFresh both listed on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange at multi-billion dollar valuations.

But a deal last week — $100 million in funding for vertical farming group infarm — brought Germany’s agtech industry into focus.

And while agriculture is still far off making the economical contribution that Germany’s well known industrial sectors do, the country still has a not insignificant 16 million hectares (39 million acres) of farmland employing 1.4% of the workforce, around 700,000 people.

The country also has significant scientific strength from which to scale startup innovations designed to make agriculture more efficient, resilient and productive. The country is leaning on its long history in research and development, placing particular emphasis on technological innovation via its academic institutions. Humboldt University in Berlin, TU Munich, Christian-Albrechts University of Kiel and Hochschule Weihenstephan-Triesdorf are all taking the lead in transferring research into entrepreneurship. In particular, Frauenhofer Institut, a scientific institution, has emerged as a strong player in agtech innovation.

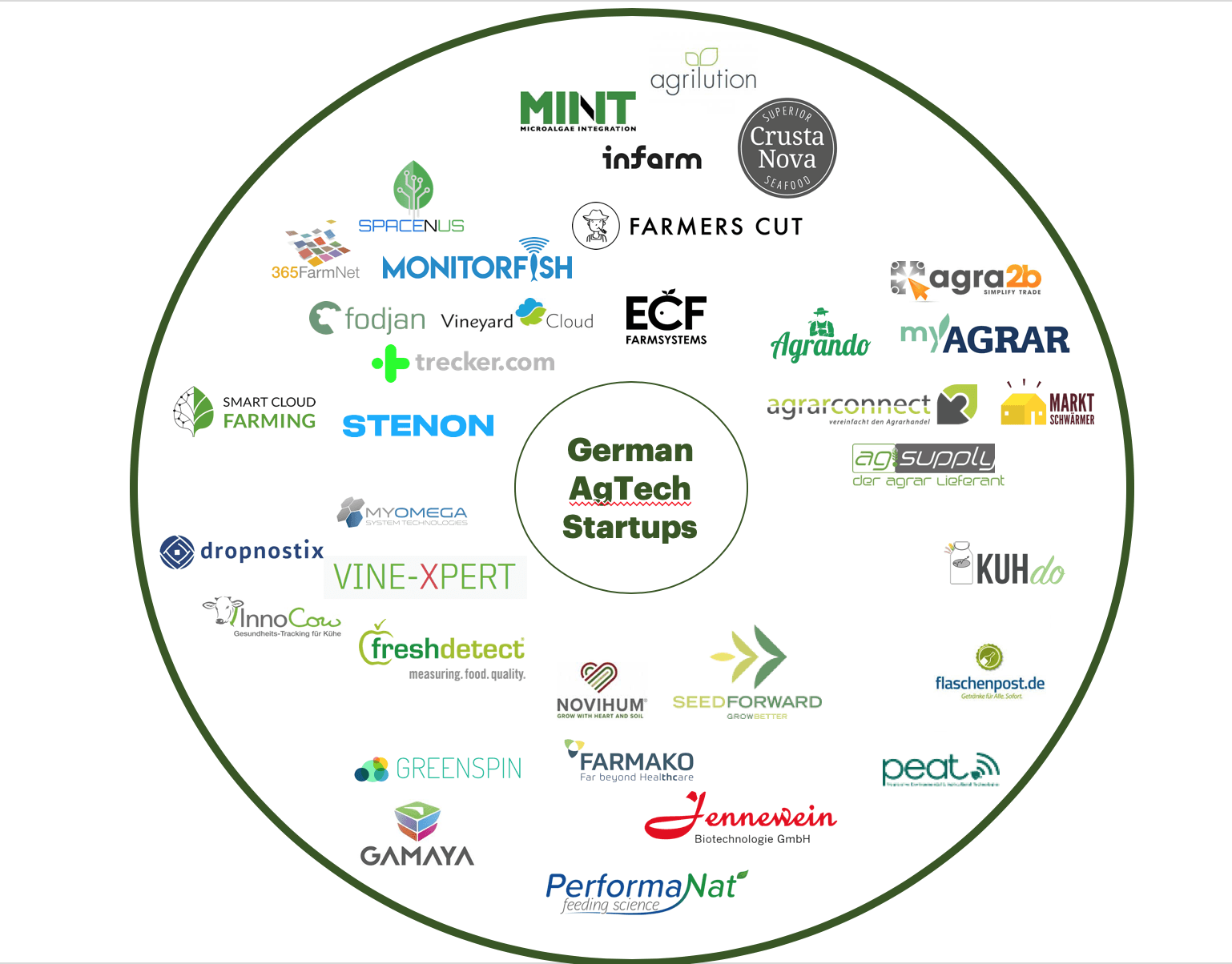

A shallow but wide startup pool

Among all of Germany’s startup sectors, agtech comprises the smallest share in terms of both the number of startups and the amount of venture capital invested, according to EY’s Start-up Barometer. The sector claimed only €29 million out of a total €4.6 billion in startup investment last year.

That said, entrepreneurs arriving on the scene are targeting the entire food value chain, addressing traceability, transparency, and helping the sector develop more sophisticated data tools and resources through the integration of sensors, imagery, machine learning and climate intel. More than 30% of startups focus on plant products and processing, and 10% are homing in on agricultural techniques. Two successful startups, Agrando and Agra2b, are helping to digitize agricultural trading. And increasing pressure on the sector to enhance sustainability has yielded new bio-based products companies.

Because of Germany’s short supply of private investment capital in agri-foodtech, startups have to think creatively about where to go for funding and support.

SeedForward, a Niedersachsen-based startup developing biotechnology supplements, launched with €135,000 in seed capital from the government’s Exist programme (see below) and enrolled in a European accelerator for startups developing climate focused solutions, Climate-KIC. The company then graduated to Seedhouse, an agriculture-focused accelerator program backed by German companies Grimme, Krone and Lemke. It has secured funding from two foundations, including the Aloys and Brigitte Coppenrath Foundation and impact investor DresInvest.

“Many startups don’t think offtalking to foundations but for us this was a very good way to get financial support, but at the same time stay independent” SeedForward’s founders say.

PEAT, a Berlin-based deep learning startup that caters to small farmers, has gotten funding from mission-focused venture investor Atlantic Labs, Bundesverband Deutsche Startups and Index Ventures for its app that can diagnose plant disease, pest damage and nutrient deficiency. Simone Strey, who co-founded PEAT, says financing sources for startups focused on small-scale farmers are scarce.

“Investments are usually going into innovations which are aimed at big industrialized farms. Small farms are often left out, although they produce 70% of the world’s food and provide livelihoods for millions of people,” Strey says. “I wish to see more engagement supporting innovations which are addressing the challenges of global small-scale farming.”

Government Support

With research institutions serving as an early seedbed for innovation, the German government is seeking to improve the infrastructure for ideas to transition into startups. Providing critical early-stage funding is one area of focus. The Exist Business startup grant, for example, supports students, graduates and scientists from universities and research institutions looking to turn their ideas into businesses.

The German Ministry of Agriculture and Food (BMEL) offers a more agriculture-specific funding scheme called Deutsche Innovationspartnerschaft Agrar (DIP). The program offers grants for agtech startups aligned to the UN Sustainable Development Goals. DIP’s first grantee was to Kiel-based KUHdo, which is helping milk producers to hedge milk prices.

BMEL also offers funding for companies field testing digitization technologies—a key priority for the government. “We want to encourage precision farming through digitalization,” says agriculture minister Julia Klöckner.

Klöckner, who took office in 2018, has been publicly drawing attention to the importance of agricultural innovation and the need for greater cooperation between startups, investors and farmers. While most of the ministry’s funding makes its way to corporate R&D and research institutions, rather than entrepreneurs, actors across the agrifood tech sector say they are witnessing payoffs from such conscious efforts to seed innovation.

“When I started in this business 10 years ago, the agtech startup scene made up 1% of all German startups. Today it is around 5%,” says Rolf Nagel of Munich Venture Partners, a generalist venture capital firm that is increasingly seeing and seizing agrifood tech opportunities. The firm has backed startups such as Novihum Technologies, which focuses on soil nutrition, and Prolupin, an alternative protein venture.

“One can tell that things are moving, and various models are evolving towards an established agtech ecosystem,” Nagel adds.

Lack of specialist investors

Finding investors with a preference for small versus industrial-scale agriculture would be a luxury in a market that still lacks specialist agtech investors.

“It has definitely improved during the past 10 years, but still many investors are skeptical towards agtech innovations, because they don’t really understand the field,” says Novihum’s CEO Andre Moreira, whose company secured funding from Munich Venture Partners.

Indeed, both the German government and private investors appear to be risk averse when compared to the US, Israel or Australia. Startups operating in more established and predictable lines of business are more likely to raise capital than those introducing ground-breaking new ideas. Also, Moreira adds, startups that position themselves in fields more familiar to investors, like tech, digitalisation, and big data, are also more likely to secure funding.

Munich Venture Partners, for example, is increasingly interested in agtech, but looks for companies approaching it through big data, autonomous systems, drones and robotics, and whose ideas are internationally scalable.

“We think that startups which are providing the farmer with more information in order to work more efficiently are going to take the lead,” says Munich Venture Partners’ Nagel.

The firm has also dipped its feet in biotechnicals. It is seen as having somewhat higher risk tolerance than others, like M Ventures.

M Ventures, Merck’s venture arm, is another generalist firm that is becoming more active in agtech, but it only invests in startups that can demonstrate scientific proof of concept. So far, the firm has backed Dutch alternative protein company Mosa Meat.

A few agriculture and food-related companies have corporate venture initiatives that are supporting agtech startups.

Munich-based BayWa, a trade and logistics company serving the agriculture, energy and building materials sectors, runs a startup-program in partnership with Raiffeisen Ware Austria. The program is working with 16 European agriculture startups covering agricultural engineering and technology, organic agriculture, animal husbandry and feed, big data and supply chain management. Two German startups are part of the cohort: Agrar2b, a trading system for operating material, and Landpack, ecological insulated packaging for food. Some will have the opportunity for investment and follow-on support from BayWa after the five-month program.

“As a corporate investor, BayWa has the advantage of expertise. We have the opportunity to support a startup with our competence, to open up our network, do market research and do field experiments” says Marion Meyer, BayWa’s head of corporate business development at BayWa.

“It’s always a plus if the ideas meet our field of business, but we are interested in any kind of agtech business,” Meyer adds. BayWa’s main criteria is that the startup’s use to the farmer needs to be clear and that its business model is consistent.

Einbeck-based seed company KWS Saat also has a venture initiative, but it is highly focused on precision farming and only looks for startups aligned to its own business model.

“As long as the idea is scientifically sound and unique, we also like to take high risks,” notes Alexander Wiegelmann, KWS’s head of transaction. Wiegelmann says agricultural innovation in Germany needs more support to help transfer technology into new businesses. The market is not as competitive, he adds, as others like France, where startups benefit from tax breaks.

Bridging ecosystem gaps

A lack of ecosystem support, including from the policy side, could explain why most of the investment capital entering Germany’s agtech space has gone into early funding rounds: there simply aren’t enough mature companies to absorb later-stage capital. (Berlin-based indoor farming infarm, which just raised $100 million, is an exception.)

Berlin-based venture capital fund Atlantic Labs is one of the few private investment firms working to build new food and agtech companies and commit investment capital at the pre-seed stage, where grant funding is most common. The firm does this through its Food Labs, which it launched three years ago.

“Food is influencing humans’ microbiome and therefore their health. In a society where self-perfection and health become the focus of attention, consumers are going to be particularly interested in innovations addressing these aspects,” Atlantic Labs CEO Christophe Maire said at DLD, a conference focused on digital technologies’ impact on lifestyle and community, the year after Food Labs was launched.

Since then, the firm has invested in infarm and Potzdam-based soil analysis company Stenon, as well as Dutch lab-grown meat company Meatable.

Atlantic Labs is backed by recognized family-run food and beverage companies like Dr. Oetker, brewery Bitburger Braugruppe and ingredients firm Döhler. These companies have expressed particular interest in alternative proteins and sugar replacements.

Atlantic Food Labs, along with corporate-based Seedhouse, are among the few agrifood tech incubators and accelerators in Germany, though these appear to be growing in number. The landscape also includes Agro Innovation Lab, Schmiede.ONE, and smartHectar.

International fairs, conferences and competitions are also increasingly playing a role in spotlighting agtech innovation and startups. The main one is the international congress, Farm & Food 4.0, which was initiated in 2016 and takes place annually in Berlin. The event brings together European players with backgrounds in economics, politics, and science to discuss agricultural innovation in digital transparency, smart farming, automation and sustainability. Key topics at the 2019 congress focused on food security, new digital processes along the value chain, and big data.

Others includes Agritechnica, an annual agricultural technology fair, and Green Week, a global fair for the food, agricultural and horticultural industries. Both events are providing agtech startups with a platform to pitch their ideas and to meet various stakeholders.

Media is also helping to cultivate more awareness around Germany’s growing agrifood tech sector, including specialized media like f3. Founded 2018, f3, which stands for farm, food, future, is the first magazine dedicated to agricultural startup innovation. The publication’s goal is to both report on the agrifood tech trends and foster a community among startups, farmers and investors.

“Three times a year we invite farmers and entrepreneurs to a so-called Scheunengespräch to encourage the cooperation between startups and farmers,” says Eva Piepenbrock, editor at f3. “We think it is essential to create a strong network between those two parties in order to gain practice orientated knowledge.”

Regulation and red tape

Bridging the urban-rural divide is something Benedikt Bösel, chair of German startup association Bundesverband Deutsche Startups would like to see more players in the agrifood tech sector support.

“We need to bring startups on the farms and into the rural area. Only through the interaction with farmers and the understanding of farmers’ lives and needs can entrepreneurs develop products and services that offer direct and true benefits to the farmer,” says Bösel, who is himself a farmer and provides field space for startups to test their products and services.

For Bösel, however, the real issue holding back innovation in Germany is policy. “As of today, the regulatory framework and bureaucracy often interfere with the development of startup products. We still have a lot to do when it comes to developing an innovation-oriented environment, specifically for agtech startups,” he says.

In particular, Bösel would like to see more action on how to sustainably shift food and agriculture on a systemic level. “Sustainability is not enough. Our aim must be to regenerate. Startups that develop products to help regenerate soil, water and the ecosystem could be a dominant force in shaping the future of agriculture.”

He adds, “Germany has the potential to be at the forefront of this development.”