With the US ag spray drone landscape set for a major shakeup as the FCC blocks new foreign-made models and critical components from the market, AgFunderNews caught up with two new players hoping to fill the vacuum: Revolution Drones and Exedy Drones.

Exedy Drones: automotive know-how pivots to ag aviation

A business unit of EXEDY Globalparts Corporation, best known for clutches and powertrain components, Michigan-based Exedy Drones has been a couple of years in the making, says Scott Binder, VP engineering, operations, and technology.

“We used to have a big plant in Knoxville, Tennessee that made torque converters and manual clutches for American and Japanese OEMs. But the tech had kind of reached a pinnacle from an internal combustion standpoint, so we knew they probably weren’t going to spend hundreds of millions developing new transmissions that don’t get any better fuel economy or performance. And electrification was coming.

“So we had a choice: stay and fight to be the lowest bidder or look at different markets. So we said, What market can utilize our current expertise in CFD [Computational Fluid Dynamics]? In the late teens, [Japanese parent co] EXEDY [Corp] started developing smaller drone propellers and motors, and then in 2023 they invested into a Turkish ag drone company called Baibars.”

Binder then started talking to farmers in the US and comparing Baibars’ developmental drones to drones from [market leader] DJI, and “it became clear that the market was screaming for something locally based,” he says. “There was [Texas-based] Hylio but we were like, man, everything’s coming in from China.

“So we did feasibility studies and by 2024 we decided that we’ve got a real business case here. We’re an automotive company and we can really add some value. So we turned our prototype build facility here in Michigan into a drone manufacturing facility.”

The road to a 100% US-made drone

Right now, although the bulk of the parts to make its drones are sourced from the US, Exedy Drones “still has to rely on a few foreign systems at the moment,” says Binder.

“If it already had a pre-existing FCC ID, it’s fine to use, so we can still get those components, but we are trying to bring a lot of that production towards the US.

“And not just because of the FCC ban, it’s just as much about having a secure supply chain. This industry has had a lot of problems over the past couple of years with getting parts. What we were hearing from people is just give me something that works that’s serviceable with access to parts.”

In the short term, batteries are the biggest issue for firms trying to assemble drones in the US, along motors and remotes [handheld ground control units], he says.

“It’s a lithium polymer battery, so even if you do find a local supplier, the lithium is coming from China, more than likely. But we’ve been developing a lot of components that we will eventually produce and establish here in the US.”

He added: “From the battery standpoint, the drone market isn’t [a] primary [market]. We have engaged automotive battery suppliers, but drones don’t necessarily have the volumes to interest them, or the subsidies. So it will take time. But every drone we release will have more US content in it until we have a 100% US drone.”

Exedy Drones’ first products will be in the 50-70-liter payload range and will be launched this year, although exact timing will depend on regulatory factors, he says. “We’re working with AcuSpray on dealer development and American Autonomy on the software.

“The FCC came out in December with its main statement, and it was a case of what does this mean? Since then, they have put out more things [about exemptions and timeframes] that help clarify things. But we’ve got a lot of positive feedback and there’s a lot of excitement.”

Revolution Drones: assembling a domestic drone ecosystem

Revolution Drones, meanwhile, is the brainchild of Russell Hedrick, a first-generation farmer growing corn and soybeans on a 30-acre farm in Hickory, North Carolina.

Hedrick, who holds his state’s record for soybean yield and the world dryland corn yield record, has been a long-time user of DJI drones and started working on building a US drone business about two years ago.

“We already had a team that could build software and apps. And then for hardware, we partnered with a drone company out of Brazil called GTEEX. But the flight controller is 100% designed by us.

“We were going to build the drones in Brazil, and then the FCC decided to drop a nuclear bomb in December [by blocking not just selected new Chinese drones, but all new foreign-made drones and components], so everything is now moving to the US.

“We have a company in North Carolina that builds our electronics. We have a company in Nebraska that builds our plastic components. We have a company in Indiana that builds our wiring harnesses. We have a company in Illinois that builds our tanks. We just gave them the engineering designs, the drawings, and tapped into that existing infrastructure to build our components. Then final assembly is in North Carolina and either Kansas or Nebraska.”

“We launched our first drone at [farm show] Husker Harvest Days last year. We’ve already sold about 250, we’ve made another 100, and we’ll have another 200 made by end of February.”

Scaling US manufacturing under new FCC rules

Hedrick’s motors and radar systems are currently sourced from China but production is switching to South America, he says.

“For batteries, we’re still using Chinese components but we are working with two companies in the US on this. One has already built us prototypes and the other should have them by June. The problem is cost. If you’re paying four times as much, that’s hard to stomach.”

For motors, he says, “You’d have to cut down the size of our drones by 80% to use an American-made motor right now. And so we’re going to be sourcing them from South America, which is non adversarial, so we’ll just have to go through the FCC’s exemption process for those.”

He adds: “We have a 100% American-made mapping drone that we’re launching now, the independent series spray drones that are 29-gallons or under and the [new] Revolution series, which are 30 gallons or more.

“Our propellers are also at least two times thicker than some competitors’, which means the blades flex less and we maintain a more constant thrust throughout the flight. Our processing speed is also way faster than our closest competitors. It was a case of can we build something for the American landscape? Can we be more efficient, can we go faster, but also at larger coverage area in width?”

It will take a while for the market to transition to US-made products, and existing pre-authorized products from Chinese firms such as DJI are still available and affordable for the time being, he said. But there are challenges.

“If you want to get a DJI drone right now, you can still get a T50, but it’s hard to get parts. So [if something goes wrong] you may find you have a $35,000 paperweight.”

Acreage soars, but drone sales slump amid import shock

According to the American Spray Drone Coalition’s annual industry survey, total treated acreage covered by ag spray drones in the US surged by 58.7% year-over-year to 16.4 million acres in 2025.

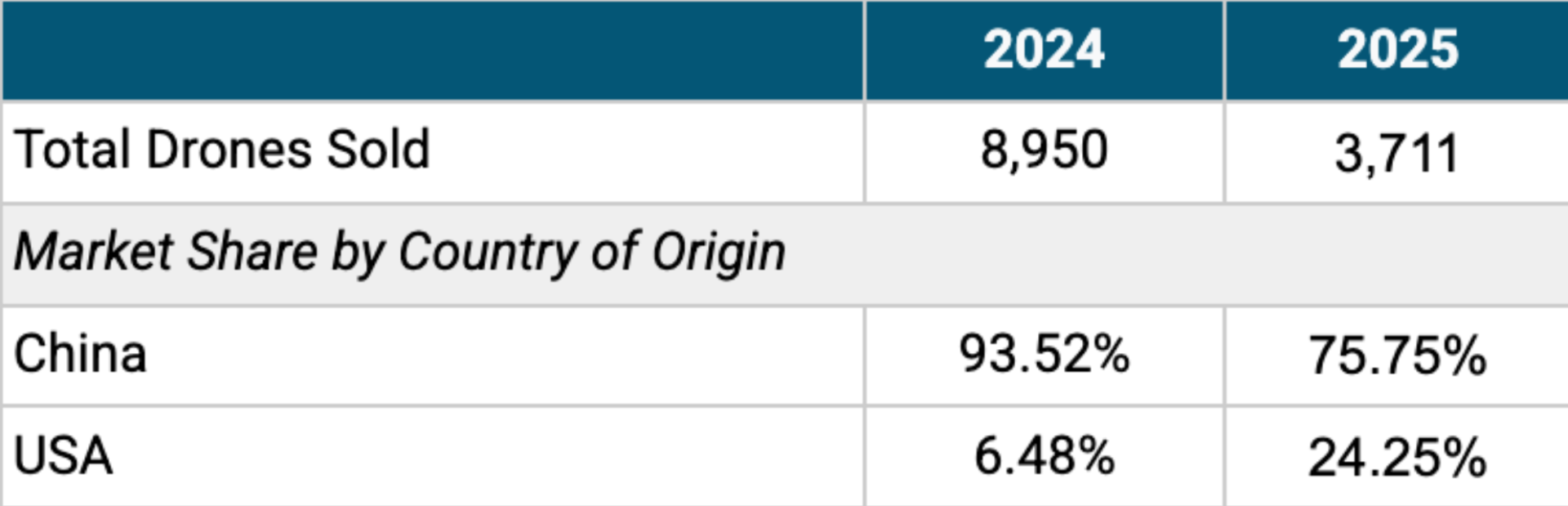

However, sales of new spray drones plummeted 59% from about 8,950 units sold in 2024 to about 3,711 in 2025 due to import restrictions on Chinese supplier DJI (the US market leader) with shipments blocked by US Customs and Border Protection on the grounds that DJI may be using forced labor. DJI says such claims are “unsubstantiated and categorically false.”

The average price per acre sprayed dropped from $21 to $13, reflecting “aggressive market competition,” says Eric Ringer, founder at American Autonomy Inc, which develops software for US drone makers. “ASDC members report substantial undercutting by non-Part 137 operators* willing to accept lower rates, particularly in the corn belt.”

Non-Part 137 operators are drone spray providers not operating under the FAA’s Part 137 agricultural aircraft certification, which traditionally governs crewed crop dusters and some fully certified drone operators.

According to Ringer, while the market share of US-made drones nearly quadrupled in 2025, this increase “primarily reflects the vacuum left by the sudden drop in DJI imports rather than a sustained, competitive shift. XAG and EAVision, both Chinese drone manufacturers, most benefitted from DJI’s import restrictions.”

A rapid reshaping of the market

The figures were released after the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC) sent shockwaves through the US drone market in December, adding not just DJI, but all new foreign made drones and critical components to the covered list of communications equipment and services “deemed to pose an unacceptable risk” to national security.

In an instant, this cut off FCC authorization for any new drone models—or essential components such as motors, flight controllers, navigation systems, and batteries—manufactured outside the US, a sweeping intervention in a sector where overseas suppliers dominate.

Crucially, the restrictions do not apply to foreign-made drones that already hold FCC authorization, while impacted companies can also apply to be exempted from the covered list by submitting requests for conditional approval. Certain drones and critical components on the Dept of War’s Blue UAS Cleared List or those that qualify as “domestic end products” under the Buy American Standard are in turn exempted until 2027, according to a public notice issued by the FCC on Jan 7.

A Jan 21 update from the FCC also clarifies that drones from DJI, Autel, and other covered foreign manufacturers that were already authorized before Dec. 22, 2025 can continue to receive firmware and software updates through at least January 1, 2027.

But while today’s fleets remain legal, tomorrow’s upgrades are in doubt. Drone technology evolves rapidly, with manufacturers rolling out new platforms, sensors, and flight systems on a near-annual basis. Blocking new authorizations therefore places Chinese players such as DJI and XAG at a long-term disadvantage in the US.

The result is likely a rapid reshaping of the market, as domestic manufacturers scale up and overseas firms explore partnership models—licensing designs or software to US companies that can assemble and manufacture drones domestically.

Further reading:

Made in America: FCC decision sparks scramble to localize ag spray drone production

Ag spray drone leader DJI faces uncertain future in US; sector braces for realignment

Drone maker DJI appeals court ruling: We’re not a ‘Chinese military company’