Monitoring livestock on a property with a few hundred acres is challenging enough. Doing it on a farm with one million acres is an altogether different beast, notes Drone-Hand founder Edward Barraclough, an aerial photographer-turned agtech entrepreneur using drones to cut labor costs and preventable livestock mortality.

Barraclough, who grew up on a mixed livestock farm in New South Wales, knew a thing or two about drones from his photography work, but less about the tech stack needed to turn them into a livestock monitoring tool for farmers when he launched Drone-Hand in 2023.

Teaming up with AI/ML engineer Dr. Sebastian Haan, he set out to build autonomous systems with two goals: “Reduce the number of hours spent on routine tasks [stock checks, water inspections, infrastructure monitoring, mustering] and reduce losses by knowing when animals are in trouble and need attention.”

Crucially, Drone-Hand’s system can operate offline in remote environments, says Barraclough, who is also testing the tech in feedlots through fixed-camera computer-vision deployments with the Australian arm of meat giant JBS.

By 2025 the company was testing and refining the tech across Australia, New Zealand, the US and Canada and has new trials planned for Indonesia and South America. Today it has paying users in multiple countries and is laser-focused on “ramping up commercialization and getting some revenue in.”

AgFunderNews (AFN) caught up with Barraclough (EB) to learn more about the tech and how to pitch it to skeptical livestock farmers: “I don’t start talking about the tech until we have talked about [a potential customer’s] pain points,” he says. “You can’t just come in and say I’ve got this magic tech that’s going to change your life. They’ve heard that before.”

AFN: Give us the origins story of Drone-Hand

EB: I was working as an aerial photographer in tourism, corporate videos, motorsports and everything in between. About three years ago, my dad—who’s in his eighties—was watching me take photos with a drone on his farm, and said, you know, if that could check the stock for me, I could stay on the farm longer, and it got me thinking…

At the time there were only about three or four companies worldwide doing anything with livestock and drones, so I started looking into it. How could we use machine learning and image recognition to replicate the things farmers do when they go out each day to check their stock? How many animals? Where are they? Are any injured or showing signs of potential health issues? Is there water in the troughs? Are the fences in place and the gates closed? Is there pasture on the ground?

The next issue to address was that the vast majority of farmland here [in Australia] has next to zero mobile reception, let alone a high speed internet. Maybe you do at your house, at your driveway, at the top of a mountain, but everywhere in between, there’s next to nothing. So it had to work offline in real time when the farmers are out in the paddocks. They can’t wait to go back home to find out there is a cow in trouble.

So I teamed up with my cofounder, Dr. Sebastian Haan, who’s an advanced machine learning engineer, and we started down this track.

AFN: What key problems are you solving for livestock farmers?

EB: The pain points all these farmers are facing are labor costs and preventable livestock mortality. So we’re reducing the number of hours spent on routine tasks and trying to increase profitability by knowing when animals are in trouble and need attention, to reduce losses. The sheep industry alone in Australia loses millions a year to preventable livestock mortality.

AFN: How has Drone-Hand evolved since the early days?

EB: During the first couple of years, we worked with smaller drones called quadcopters that you might use on a smallish size property, so 10,000 to 20,000 acres. But in the north of Australia, you’ve got massive properties that are up to a million acres. So we built a second product that uses long range drones that look like a small plane.

Some of our trial users [on the huge farms in the north] spend over $120,000 a year to have helicopters come in and muster cattle for maybe two weeks’ work. Our systems are a fraction of that price, so there’s a significant cost saving. Up in the north, we’re also working on autonomous mustering with an onboard reactive AI that is responding to the movement of the animals to shift the pressure on and off to get them into the trap point.

Two of Australia’s biggest helicopter mustering companies have approached us to work together to try and see where we can go with this technology because they see that drones are going to augment or assist their operations, and in the near future, possibly replace them.

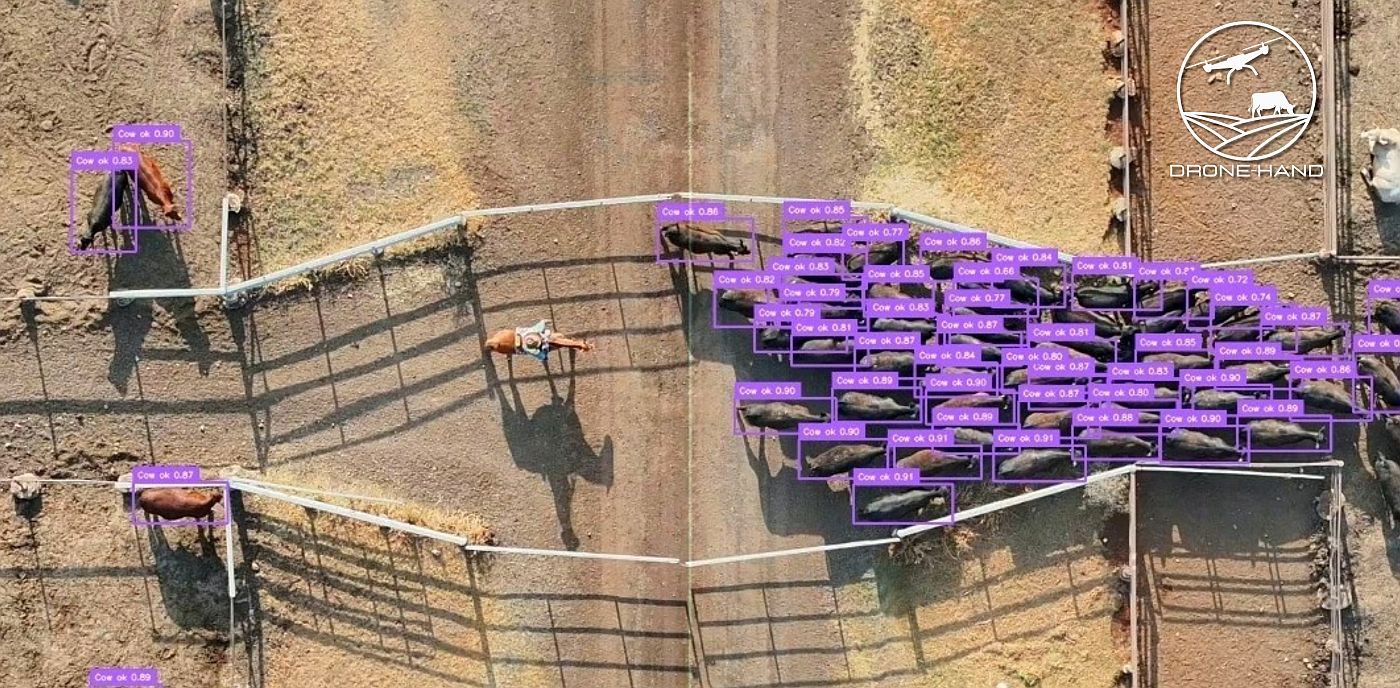

Finally, with JBS Australia and Meat & Livestock Australia [a producer-funded body that regulates standards for meat and livestock management in Australian and international markets], we’ve developed another product using fixed cameras and machine learning models and algorithms to monitor animal condition, movement, and disease on two feedlots.

So we’ve gone from, ‘How can I help my dad?’ to a product that spans everything from high density feedlots right through to million-hectare properties in northern Australia with paying users in multiple countries. Last year was all about trialing and refining and early adopters. This year’s about ramping up commercialization and getting some revenue in.

AFN: What’s the business model?

EB: The software is [paid for via] an annual subscription, but we partner with companies to provide the hardware. For smaller, cheaper quadcopters, we’re just a reseller [of drones], whereas for the larger systems in the north, we partner with the company who manufactures them.

This year, we are opening an assembly and maintenance hub in Darwin that’s going to be a joint venture between us and that manufacturing company that allows easier importing of a semi-complete drone. We finish it off, put our software and computing into it here in Australia, and from there, we can do leasing and handle maintenance and upgrades.

But we’re not tied to any one manufacturer or brand. Maybe a customer already has a drone, for example. Then they just need to download our software. If they don’t have a drone, we can sell them one as a package, as I get them at a wholesale rate so I sell to them for less than [the] retail [price] with the software subscription on top of that.

In Australia [Chinese drone maker] DJI is still the most common [drone vendor], and to be honest, they’re the best quality for the money. And there’s no real indication in Australia that we’re going to go down the route of the US [which has blocked new models from DJI and other “foreign” drone makers]. But if we do, our systems work with other drone types. For example, for the long range systems we’re using in the north we’re working with an Indonesian company.

AFN: Can you talk about the competitive landscape for drones in livestock monitoring and mustering?

EB: If we go back probably two and a half to three years, to the best of my knowledge, at that point, there were two or three companies using drones for monitoring livestock farms including Beefree Agro, and Icaerus, where you take the data, put it into a computer, and then get the results. This works well in places with high-speed connectivity. But not every farmer has a Starlink mini [a portable satellite internet kit from SpaceX designed for on-the-go connectivity] in their truck.

Another firm SkyKelpie was set up by a good friend of mine named Luke Chaplain, who is teaching farmers how to manually muster using drones. And then in the last year, Sam [Rogers] came along from GrazeMate [a new player using drones for autonomous mustering]. We all know each other and help each other, and we’re all doing slightly different things.

AFN: Where are you prioritizing efforts?

EB: There isn’t really a sweet spot. We’ve developed tech to be useful to all kinds of livestock farming operations. We’ve had significant interest from massive corporates such as JBS to family-owned properties with a few hundred acres.

AFN: How do you pitch it? What’s the ROI?

EB: It all depends on the size and nature of the operation. So for a family-owned farm of say 10,000 to 20,000 acres, I might start by asking, How often are you doing this? How many hours are you spending on that? What if you could do it in 10% of the time?

With helicopter mustering on a far larger farm, even when you’ve got multiple helicopters and people on the ground, the average is about a 70% success rate, so you’re leaving 30% of the stock out in these paddocks. If you could raise that by just 5% or 10% then that’s significant, and you’re reducing pressure on the pasture and feed. There’s more feed left for the next lot of stock that are going to be in that paddock. So I base the pitch on the operation, and on what they’re currently spending.

AFN: What barriers do you face when you approach a potential customer?

EB: I don’t start talking about the tech until we have talked about [a potential customer’s] pain points. You can’t just come in and say I’ve got this magic tech that’s going to change your life. They’ve heard that before.

Often the response is, ‘Oh, drones, I don’t want to have to learn something new.’ But then you show them that they don’t have to do anything. The drone flies itself. And then you say it costs this much, and they’re like, that would pay for itself in a day. Let’s go…

AFN: What indicators of health/disease can a drone pick up?

EB: It’s a challenge, for sure, because our drones fly about 100 meters up so they don’t disturb the animals. So we’ve built massive data sets of training material for our algorithms. It’s not just based on veterinary data, but real-world experience. If you ask a farmer what do you notice when you look at your stock? They might say something like, flystrike, which is obvious if you look at their rear end.

Sometimes it’s a case of how they are lying so if an animal is cast [physically trapped on its back or side], it’s not the same as when it’s sleeping or something like that.

And then sometimes it can be as simple as behavior. Generally, sheep and cattle will collect in similar areas together, especially at certain times of the day. If one is way over on the other side of the paddock, you might want to go check what’s going on. Is it injured? Is it sick?

We can’t say the animal has a fever or anything like that; it’s more what are the visual and behavioral indicators that would say this animal’s in trouble.

For fixed camera systems in the feedlots, however, you can get a lot closer.

AFN: How have you funded the company?

EB: Initially I funded it largely out of my previous business as aerial photographer. From there, I was very fortunate to get a few grants from state and federal government here in Australia. We then did a pre seed round of AUS $720k last year, half of which came from people involved in the ag industry, and the other half came from Radius Capital.

To answer your question, how difficult was it? It was pretty hard. There’s first mover advantage, but also first mover disadvantage. But at the point when I was pitching, we had well over 200 confirmed expressions of interest, trials running in Australia and New Zealand, and lots of data.

Further reading:

Revolution Drones and Exedy Drones target US ag spray drone market as FCC rewrites the rules

Made in America: FCC decision sparks scramble to localize ag spray drone production

Robot cowboys: GrazeMate bets on fully autonomous cattle mustering drones