TerrAvion, the San Leandro, California-based startup providing aerial imagery from manned aircraft to farmers, has raised $10 million in Series A funding.

Every week, TerrAvion takes hundreds of low-altitude flights to capture bird’s-eye views of farms and then uploads the images to the cloud within a few hours to help growers spot the early-warning signs of plant health issues and irrigation problems.

Merus Ventures, a software-focused VC investing in Silicon Valley startups, led the round. Existing investor Promus Ventures, which is an experienced remote sensing investor with stakes in drone company AirWare and satellite data company Spire, joined the round with two more tech VCs Initialized Capital and 10X Group.

TerrAvion will use the funding to expand its presence in key agricultural areas such as the Great Plains, Mississippi Delta, and Pacific Northwest.

TerrAvion offers farmers images from 12 flights over their land per growing season for as little as $4 an acre dependent on the region. These images provide a low-cost alternative to drone imagery and a higher resolution than satellite imagery, according to Robert Morris, CEO of the company.

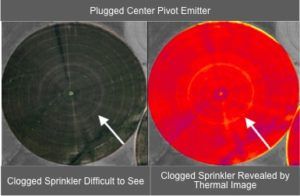

The cameras attached to the planes take images across five bandwidths: red-green-blue (RGB), near-infrared (NIR) that is good for looking at chlorophyll levels in the crops, and long wave infrared that can provide thermal readings for temperature measurements.

TerrAvion provides farmers with the following images:

- a regular color image to see details of what is going on in the field – details that Morris argues can be lost in satellite imagery

- a color infrared image, which is similar to the color image but with the red channel providing infrared readings relevant for detecting chlorophyll and therefore plant health

- an NDVI image, plotting the fields against the normalized difference vegetation index

- a thermal map, to help identify warm and cold spots, water levels and therefore any issues with irrigation etc.

Satellite imagery can provide all of these images, but at a resolution that’s less useful to farmers, argues Morris.

“For thermal mapping, for example, satellite images can only provide 100mx100m in resolution, giving you only a few pixels to work with and so much is averaged together,” he said. “This is useful if you want to know what the transpiration rate is for California, but not if you want to know if your drip irrigation isn’t working properly, or to find out where water is disappearing to.”

TerrAvion does not offer recommendations on the images it processes and provides to farmers, instead preferring to integrate with offerings from agronomists and retailers who can provide that advice to the farmer as part of their usual service. Recently, TerrAvion announced two partnerships to this effect with Servi-Tech and CHS, whereby TerrAvion can be added as another line item for farmers taking up their in-season crop analysis services.

“We want to provide directly actionable information but stay out of agronomic interpretation and recommendation,” said Morris. “We know thermal rings around a center pivot means there’s an issue, but it’s not our call whether the farmer needs to fix a nozzle or change the chemistry. There are situations where a grower might do any of those things, and we want to point out they have those rings, but then talk to local experts about what to do.”

know thermal rings around a center pivot means there’s an issue, but it’s not our call whether the farmer needs to fix a nozzle or change the chemistry. There are situations where a grower might do any of those things, and we want to point out they have those rings, but then talk to local experts about what to do.”

By publishing its API, it is also partnering with other remote sensing companies such as FarmSolutions, which developed software originally for drones to provide data analysis and a task management workflow for farmers. FarmSolutions is now integrating TerrAvion’s aerial imagery with its drone imagery and combining them with other farm data such as soil moisture monitoring, nutrient and chemical applications, and yield data to give growers a better understanding of the health and growth of their crops in real-time.

Morris also indicated that other, similar partnerships were in the making, including with a satellite imagery analytics service.

TerrAvion contracts pilots and planes from flight schools, charter companies, and other providers, who are given the data they need to collect at the start of each week. They’re each graded on what they produce with the hope of creating a sort of Uber for aerial imagery, said Morris.

By way of competitors, John Deere spinout GeoVantage is the biggest one, although using very different processing technology.