RipeLocker—the startup behind drum-sized vacuum chambers that dramatically extend the shelf-life of fresh produce—is developing a new shipping container-sized chamber that will allow firms to ship perishables globally without first having to transfer them into individual drums.

Seattle-based Ripelocker is best known for reusable drums that create a near-vacuum, ultra-low-oxygen environment for perishables from blueberries and avocados to flowers and hops. Unlike modified/controlled atmosphere approaches that flush sealed bags or containers with nitrogen, Ripelocker sucks out the air, monitors conditions inside, and dynamically controls oxygen and CO₂ levels.

The system has been particularly successful in stationary storage applications, enabling firms to extend selling seasons and secure higher prices, says president Brendon Anthony, PhD.

While the drums also work in transit, he says, they present challenges. First, shippers have to transfer goods from boxes or trays into individual Ripelocker drums and then load them one by one into shipping containers. And second, a container filled with Ripelocker drums holds only about half as much fruit as a palletized container.

“When you fill Ripelockers into a shipping container, you only get about half the capacity,” Anthony tells AgFunderNews. “Which is a losing proposition, because even though you’re getting the extended shelf-life, you’re doubling the freight cost.

“Our customers were telling us: We love the technology, and you’ve demonstrated that it’s better than controlled or modified atmosphere, but can you scale your chamber to the form factor of a refrigerated container?”

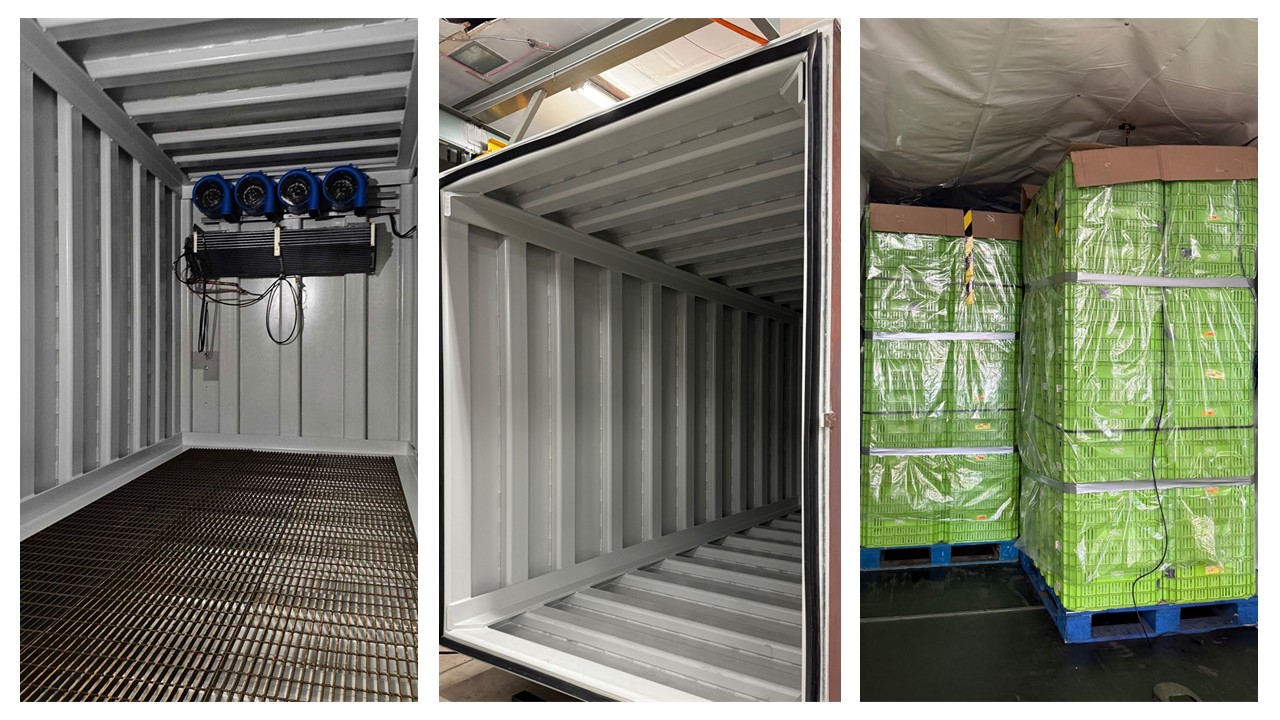

From drum-sized chambers to a 20-foot prototype

After extensive testing, Ripelocker now believes it can crack the code, says Anthony, who took the helm of the company in December.

“Low pressure storage on this scale has been tried many times before, but no one’s been able to crack the code on commercializing it. But we’re designing it in an entirely new way. We’ve built a 20-foot prototype vacuum container—the ‘RipeReefer’—and tested it with blueberries and kiwifruit. Because we’re able to put so much more volume inside, the cost per kilo goes way down.”

“The prototype is 20-foot but the commercial product will be a 40-foot container.”

He adds: “When you put [Ripelocker’s drum-sized] chambers in a container, you get around 10 to 11 metric tons of fruit versus the standard of 18 to 20 tons, depending on the packaging, based on one ton per pallet. With our new large vacuum chamber, we’re confident we can get 18 pallets in there, which would translate to 18 tons, so you only get a 10% loss of capacity. We’re hoping we can close it all the way, but it requires some engineering that we’re working on.”

Work is now progressing to switch from steel to aluminum to reduce the weight of the chamber and run refrigeration under vacuum, he says. “Previously the vacuum system existed within the refrigeration, whereas now the refrigeration is within the vacuum. Refrigeration works via airflow, so you have to find a way to do it when there’s no air.”

Fixing the cost and complexity problem

He adds: “For any agtech company to be successful, you have to create value, the tech has to be easy to use and integrate into existing operations, and finally it has to be cost effective. Our technology [via the smaller drums pictured above] worked great, but it was expensive to use in shipping containers and it was a pain in the ass. So our goal with the new form factor is to fix those last two things, making it more affordable and easier to use.”

Ripelocker is now talking to ocean carriers, logistics companies and reefer manufacturers “to help us get this to the finish line,” says Anthony.

“We don’t have the resources to build these at scale and lease them to the customers, so our goal is to finish the prototyping in collaboration with an expert in this space. And then we hope to strike up some sort of licensing deal so they will be the ones that will ultimately manufacture and lease these containers to clients in the same way they do today with controlled atmosphere containers. And then Ripelocker would take a licensing fee.”

What low-pressure storage can do that CA can’t

Asked why Ripelocker’s low-atmosphere containers are better than controlled atmosphere options, he says: “Atmospheric modification is via nitrogen displacement, where they pump in nitrogen to displace the oxygen, but if you break the seal on a CA [controlled atmosphere] container, it’s done. So if a container is flagged for inspection at customs and they break the seal, there’s no one there at the port to reinitiate that CA.

“With our technology, you can open a drum or container, reseal, it, and then suck the air out again. It’s also just better at extending shelf-life. We’ve done trials side by side with MA [modified atmosphere], with CA [controlled atmosphere], and we’ve demonstrated significantly better results.”

The aim is to have something in trial phase with customers by the end of this year or early next year, he says. “Optimistically, by next year, we hope to have something that people can use. In the meantime, we’re generating revenue from the stationary applications.”

The business case

According to Anthony: “There are growers in Latin America that want to access new markets in India, South Korea, Taiwan, where people are willing to pay more for quality genetics. Right now, they have to use air freight to make sure the fruit arrives in good condition, and that’s $3-4/kilo. By sea it’s 50 cents a kilo.

“With Ripelocker [by dramatically extending the shelf-life of fresh produce] we can buy them time so they can go by ocean. The same applies to tropical fruits such as mangoes and what have you. There are a lot of those opportunities where people today can’t access these markets because there’s just not enough time.

“Another opportunity we see is around timing. Sometimes, when a container arrives at a destination, it arrives in a bit of a collapsed market [with depressed prices]. If you can hold on to that container and store the fruit for another two or three weeks, pricing might have come back up and you can capture increased revenue.”

The third business case is just around reliability, he says. “Firms with premium varieties or brands are prepared to pay a premium to ensure that they’re delivering perfect quality every time.”

Ripelocker is also having conversations with firms transporting highly perishable fruit such as strawberries and raspberries by truck or railroad across the US, says Anthony. “This could this be an opportunity to go from California to the east coast or from Mexico into the US, so we 100% see opportunities there.”

To date, Ripelocker has relied on angel funding and has not taken on any institutional money, he notes. “Our hope is that if we can lock in this partnership, we can go out and raise institutional money.”

Further reading:

Ripelocker strikes deal with global berry producer Agrovision to roll out shelf-life extension tech

Tropic to launch non-browning bananas in March, extended shelf-life bananas by year-end

Argentina-based BioBlends taps bacterial VOCs for clean-label shelf-life extension in baked goods

AgFunder-backed Chinova Bioworks raises $6m Series A funding for natural shelf-life extender