Large institutional investors such as pension funds, endowments and foundations are interested in investing in agriculture technology (agtech), according to a new report from data service Prequin.

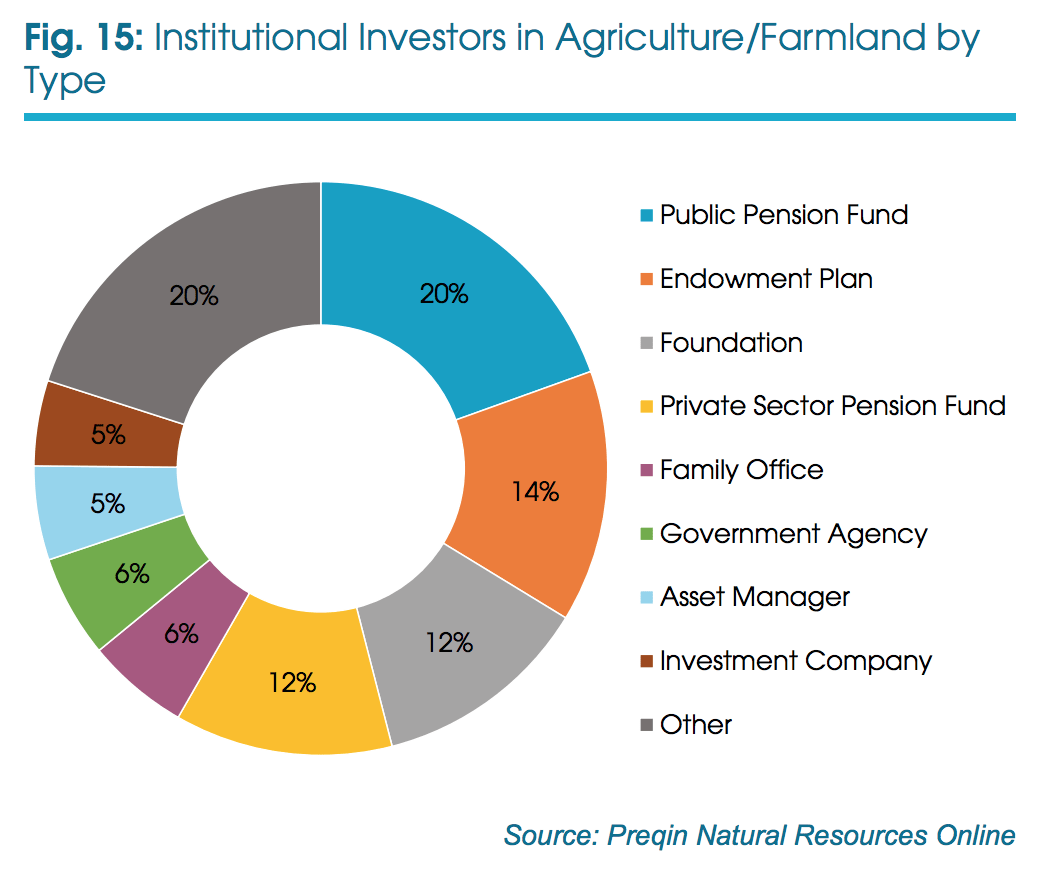

The report on the company’s 100-strong agriculture fund database references a survey of 520 large institutions that invest in agriculture. This pool of investors represents 26% of the 2k natural resources investors in Prequin’s database.

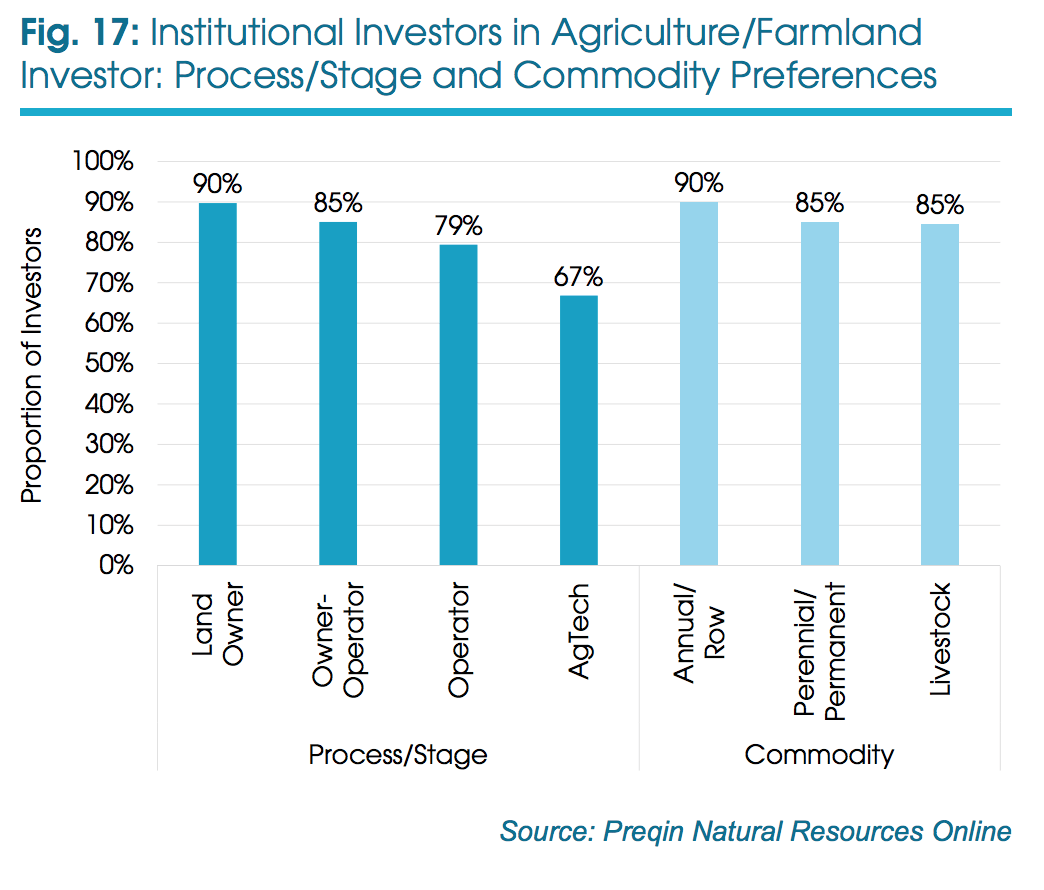

While the vast majority of the agriculture funds in the database are either farmland funds or agribusiness private equity funds, 67% of the institutional investors surveyed said they were interested in investing in agtech.

Until now, large institutional investors have typically stayed away from investing in agtech funds, which are more likely to have strategic corporate investors, family offices or individuals as LPs.

There are a couple of reasons for this. Agtech funds are still relatively small and might not satisfy the large allocation needs of a multi-billion dollar pension fund. The largest agtech funds are $125 million in size, and two of those have one or two major investors, and the average size of active agtech funds today is around $65 million. Large institutions have restrictions on the proportion of a fund they can occupy, the number of co-investors they need, and minimum fund investment size that’s often in the tens of millions.

Prequin’s report says that over 100 agriculture funds have close since 2006, representing $22.2 billion in assets under management. Of that, $3.9 billion closed in 2015, near the record $4 billion closed in 2014.

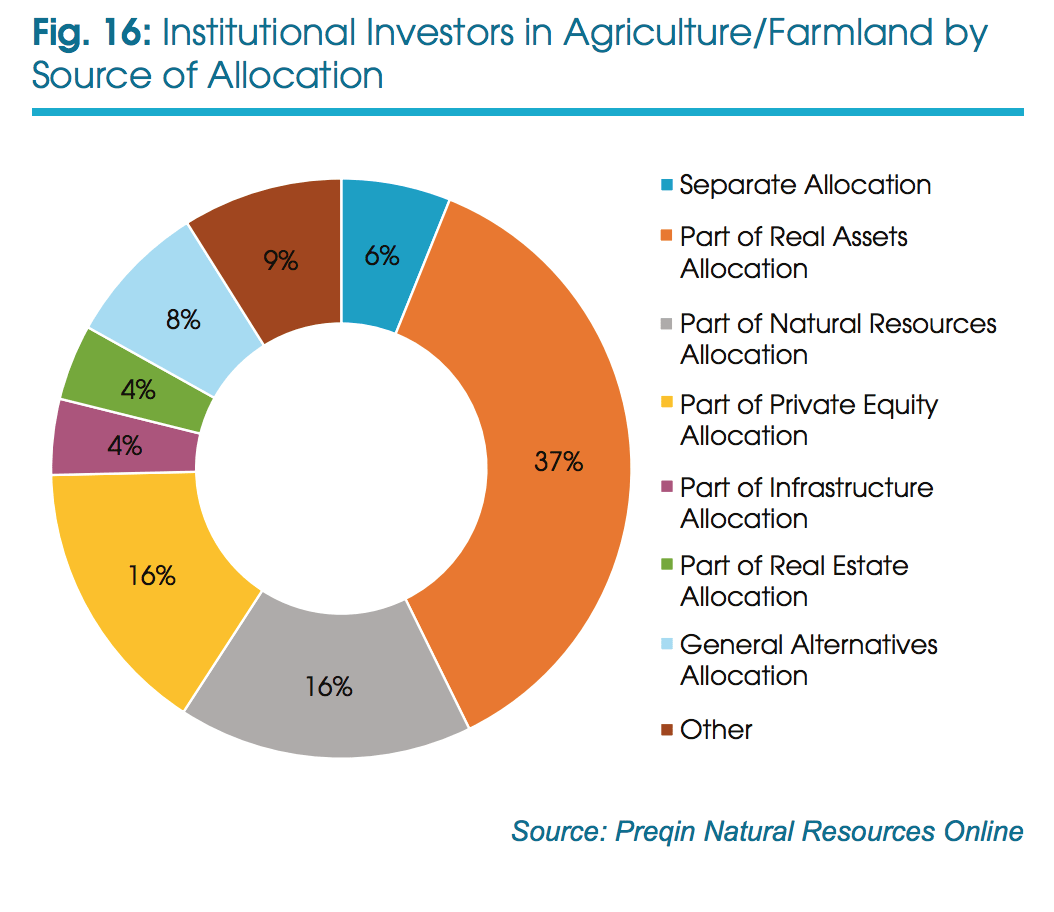

The majority of institutional agriculture investors invest via their natural resources, real assets, or private equity investment allocation. The teams responsible for these portfolios may not have the right expertise or a suitable risk/return profile for venture capital investment. Just 6% of agriculture investors have a dedicated agriculture allocation, and others invest through infrastructure, real estate or general alternatives portfolios.

Some farmland funds are starting to offer their investors exposure to agtech and agtech funds are also seeing the benefit of accessing large tracts of farmland to test technologies on. I spoke to Andy Ziolkowski from Cultivian Sandbox about this last year. He referenced Fall Line Capital as an example of a fund manager that’s investing a portion of its $127 million institutionally-raised fund in agtech alongside farmland.

International Farming Corporation, which has over $1.5 billion under management in farmland across the US, recently partnered with agtech investment firm Finistere Ventures to launch a new investment firm Willow Hill Ventures, which will invest in growth stage agtech companies and leverage IFC’s approx. 200k acres of farmland for its startups. Willow Hill has yet to hold a first close on its fund and it’s unclear whether IFC’s large institutional investor base will be investing in Willow Hill, or be interested.

Homestead Capital, the own-and-operate farmland fund manager that is raising $400 million for its second fund, is looking to partner with agtech venture capital firms and startups too. The fund invests in farmland across the Mountain West, Delta, Midwest, and Pacific regions of the US with the aim of making various improvements during its ownership.

“Partnering with agtech VCs and their portfolio companies is certainly part of our strategy,” Gabe Santos, managing partner at Homestead Capital told AgFunderNews. “We are using several farms as test plots for new technologies that we believe have potential. Since we’re a value-added investor in farmland, leveraging data, technology and analytics are key parts of our strategy. “

Fall Line Capital aside, it seems that partnering appears to be the preferred route for farmland investors to gain exposure to agtech at the moment; not investing in it. And there are two reasons why investing in farmland and agtech simultaneously out of the same fund might not make sense: the returns profiles of the two investments are very different and the internal resources and expertise needed to invest venture capital and in farmland is also very different.

“[Fall Line] are not a huge fund, so they don’t, at least at this stage, have significant assets under management, so they can balance the resources necessary for evaluating technology as well as owning and operating their farmland,” Ziolkowski told me last year. “[They] are pretty well positioned to do both because they’re more nimble, and they have a team that thinks more about operations and technology. They were also formed this way and investing into both was part of their core thesis when launched.”

But, if large institutional investors want to take advantage of the revolution that’s taking place in the agtech space, and they demand investment exposure to it alongside their farmland assets, there’s no doubt funds will find a way to give it to them!

What do you think? Is there potential to invest in agtech and farmland simultaneously? Email [email protected].