Dan Blaustein-Rejto is director of food and agriculture at the Breakthrough Institute, an environmental research organization based in Oakland, US. The views expressed in this guest article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent those of AFN.

The food system — including food production, land use change, transportation, and disposal — now accounts for over one-fifth of US greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and one-third of global emissions. According to a new report from the UN Food & Agriculture Organization and the OECD, agricultural emissions are expected to rise globally over at least the next decade. Yet researchers say that to have any chance of meeting the Paris Agreement target of limiting warming to 2°C or less, the world must reduce emissions stemming from food and agriculture, as well as other sectors.

To help reduce agriculture’s carbon footprint, the US Senate passed the Growing Climate Solutions Act last month. The bill is designed to make it easier for farmers, ranchers, and other rural landowners to generate carbon credits by reducing their carbon footprint, and to then sell the credits to companies interested in offsetting their emissions.

In the past several years, a host of companies have launched services focused on generating and selling agricultural carbon credits, mostly from farmers who adopt practices, like planting cover crops, that sequester carbon in their soil. The growing marketplace for carbon has attracted some big names: Microsoft recently committed to buying up to $2 million of credits; US President Biden has called for a ‘carbon bank‘ to help farmers get paid for sequestering carbon or reducing emissions; and CEOs of agribusiness companies like Nutrien have gone as far as calling agriculture “the solution to greenhouse gas emissions.”

However, agricultural carbon credits have always had problems that warrant caution from prospective purchasers, policymakers, and environmental groups. As more companies enter the market, new problems are cropping up.

To be effective, purchases of carbon credits must result in more climate mitigation than would otherwise have occurred. For instance, if a company buys $1 million of credits, it should generate more mitigation than if the company didn’t spend that money at all. Ideally, it should also reduce net emissions more than if that money was spent retrofitting office buildings, sourcing clean energy, investing in low-carbon R&D or on other climate-beneficial activities.

For years, organizations known as carbon offset registries — such as Climate Action Reserve and American Carbon Registry — have worked with scientists, companies, and environmental NGOs in an effort to create effective markets by developing detailed protocols. Under the rules, any project — such as an effort by a farmer to adopt no-till farming and then sell offsets — must abide by several principles, including:

- Additionality – the project must result in net GHG reductions that would not have occurred in the absence of the market. If a company, instead of reducing its emissions, buys offsets from a farmer who would have reduced their emissions regardless, they are further contributing to climate change. Although it is impossible to guarantee a project is additional, offset registries have developed several tests to assess additionality, such as evaluating whether changing farm practices would have been financially beneficial without offset payments.

- Permanence – offsets must arise from GHG reductions that are permanent. Projects that reduce emissions, such as methane emissions from manure or nitrous oxide emissions from fertilizer, are generally considered permanent. However, storing carbon in soil or even trees is unlikely to be permanent. If a farmer stops practicing no-till, switches crops, sells their land, or is subject to extreme weather that erodes their soil, for instance, the carbon removal can be reversed. Registries try to minimize the risk of reversal by requiring farmers or other project developers, in some cases, to monitor and report on projects for 100 years and essentially pay for an insurance policy against reversals.

However, few projects have gotten off the ground. For example, only two projects generated carbon offset credits under the rules developed by the Climate Action Reserve and American Carbon Registry in 2010 for reducing emissions of nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas. No farmers have generated credits under a protocol for reducing methane emissions from rice despite the fact that the offsets can be sold in the California cap-and-trade program where offset prices are relatively high.

Put simply, following the protocols has been cost-prohibitive. There are the expenses of buying new equipment, procuring seeds, or potentially seeing yields decline. But one of the largest expenses is hiring third-party companies to measure soil carbon levels, observe farm management practices, provide all the relevant documentation, and otherwise verify that projects have the climate benefits they claim. The Environmental Defense Fund, which has extensively researched agricultural carbon markets, estimated that this monitoring, reporting, and verification process costs more than the potential revenue for an average rice farm.

New efforts have sprouted trying to cut these costs while ensuring that emissions are reduced, carbon is sequestered, and farmers are paid a fair price. In just the past two years, at least eight companies have launched carbon credit programs: Bayer, CIBO, Farmers Business Network, Indigo Ag, Nori, Nutrien, the Soil & Water Outcomes Fund, and Truterra.

Although some companies, such as Indigo Ag, hold themselves to similar standards of additionality and permanence as offset registries, the standards for others are worryingly low, with little public oversight or input.

Several carbon credit programs make little to no effort to ensure GHG reductions would not have occurred in their absence; that is, they have practically cast aside the notion of additionality.

Instead, some are paying farmers who have already been using low-carbon farming practices, and then selling carbon credits to companies that claim the credits are helping offset their GHG emissions. For example, Truterra — a sustainability-focused subsidiary of Land O’Lakes — has sold carbon credits to Microsoft generated from farms that have been using no-till or cover crops for up to five years.

There’s good reason to acknowledge and perhaps reward farmers who have been early adopters of low-carbon practices; they are environmental leaders. But farmers’ past actions can’t reasonably be used as offsets for companies’ current or future emissions.

There is also a growing number of carbon credits being marketed without any assurance of keeping carbon in the soil; that is, permanence. Several programs don’t require farmers to enter into multi-year agreements or otherwise guarantee that they will continue using low-carbon practices for the decades required to ensure carbon dioxide is permanently removed from the atmosphere. CIBO Impact, for instance, only requires farmers to commit to a one-year term in order to generate carbon credits and get paid. After that, participating farmers could theoretically give up no-tillage, switch crops, or otherwise undo any carbon sequestration. While short contracts surely lower the barrier to farmers to enter the carbon market, they also erode the quality of the carbon credits.

With the wide range of rules and quality in the agricultural carbon credit market, it’s increasingly complicated for companies to find high-quality offsets. Although Indigo Ag and CIBO both sell a one-ton carbon removal credit, the actual climate benefit of these credits can be very different.

How to improve

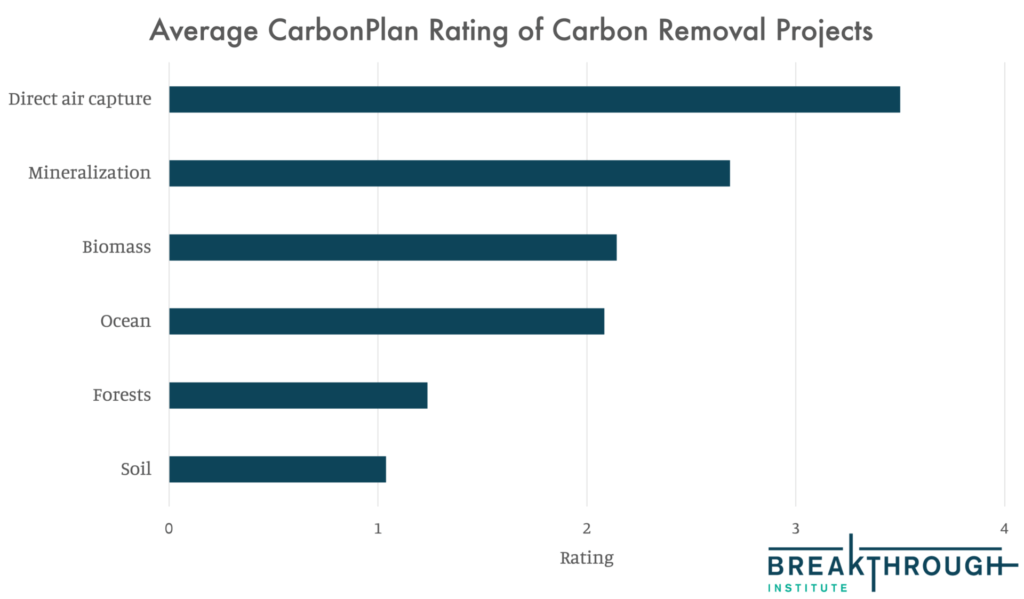

Several improvements would help. Industry groups or the US federal government should create minimum standards for what counts as an agricultural carbon credit. Furthermore, companies that purchase credits should publicly release details. For example, they could submit information to CarbonPlan, a non-profit that documents and assesses company efforts to remove carbon dioxide.

Ultimately however, companies — along with the investors and people who judge their climate strategies — shouldn’t prioritize offsets in the first place. Too often they don’t lead to the climate mitigation they claim. As Jon Foley, executive director of Project Drawdown, recently proposed, companies should instead:

- Reduce their own emissions as quickly and as much as possible;

- Donate to causes that help low-income and vulnerable communities reduce emissions and become more climate resilient; and

- Only invest in carbon removal, such as low-carbon farming, to address their historic greenhouse gas emissions.

Given the rising popularity of agricultural carbon credits, it’s urgent that the farming and climate community fix the problems in the marketplace. But more than that, companies must be more ambitious in cutting emissions in their own supply chains as much and as quickly as possible.