Aerial imagery and analytics company Ceres Imaging has raised a $5 million Series A round of funding led by Romulus Capital. The company, which focuses exclusively on the agricultural sector, has raised $8 million to date, in addition to receiving grants from Elemental Accelerator, the USDA, and the State of California.

Ceres will use the new funding to increase scale in its current markets, speed entry into new crops, and hire additional staff.

Aerial imagery for agriculture

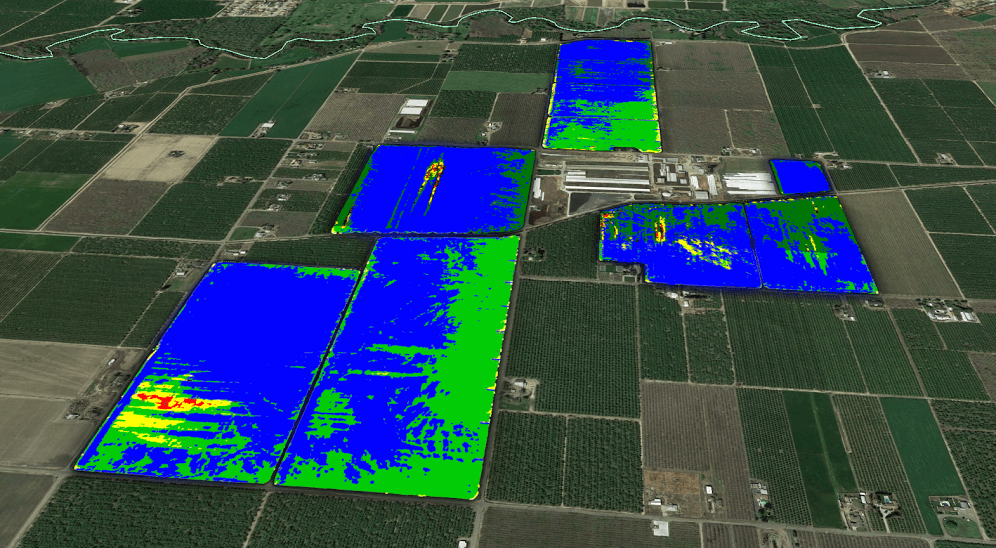

Based in Oakland, Ceres captures, processes, and delivers high-resolution spectral imagery-as-a-service for agriculture. To capture the most effective images and data, it places its proprietary, custom-built sensors on fixed wing aircraft, which it says enables it to gather data at a higher resolution and quality than satellite imagery options with far greater scale and consistency than is possible with drones.

“Other companies have been unsuccessful because they just measure NDVI, which is a measurement of the crop’s leafy plant matter. It shows the number of leaves per unit area in a given pixel,” CEO and founder Ashwin Madgavkar tells AgFunderNews. “This technology has been around for decades, but it doesn’t really provide value for the farmer. It tells you that an area of the crop is weak, but it doesn’t tell you why it’s weak. Instead, we can turn the spectral imagery into measurements of plant physiology.”

These measurements, which are generated by Ceres a team of PhDs, data scientists, and engineers, shows growers the water and nitrogen content of crops at the plant level, offering them early warnings of poor plant health and irrigation management throughout the growing season while there is still time to act.

There is no upfront cost or hardware that growers must buy, and customers pay by the acre on a monthly subscription basis. Growers can select how frequently they would like to receive images each month, paying according to each package. To conduct the flyovers, Ceres hires pilots located in the area and pays them on an hourly basis.

“Another advantage to a plane is that there are a lot of Cessna aircraft and airports around in agricultural areas. We ship a sensor and a tablet to the pilot, which he or she attaches to the plane. The tablet acts as a guidance app,” Madgavkar says. “This model allowed us to become operational in Australia in about one week.”

The company has imaged hundreds of thousands of acres in the US and Australia and covers a variety of crops ranging from tree nuts and vegetables to corn and soybeans, he adds.

An ongoing debate

There’s an ongoing debate about the merits of obtaining aerial imagery for agriculture using aircraft versus drones versus satellites. Although drones have been the sexy, futuristic tech du jour, Madgavkar is steadfast in his decision to use fixed-wing aircraft.

“Our approach is to use the cheapest way to get the data, and right now that’s a plane. We can fly much higher for much longer periods of time. A drone can fly for hundreds of feet for 30 minutes, so you can cover about 100 acres with a drone and about 10,000 acres with a plane,” he explains. “There’s also the fact that farmers don’t want to do these things themselves. They don’t want another chore.”

He isn’t opposed to drones, saying that he would be happy to use them if and when they become viable.

“We have surveyed the agtech market for a couple of years, and Ceres stood out. Ceres combines better imaging technology, best-in-class scientific analytics, a world-class team, and a really humble and collaborative approach to a massive, intelligent, and hungry industry that is often tricky to sell into,” said Krishna K. Gupta, founder and managing partner of Romulus Capital, in a press release. “Unlike most of its competitors, Ceres has found a way to create a measurable impact on the bottom line for its customers.”

Competition isn’t the challenge

Competition isn’t Ceres’ biggest challenge, however, according to Madgavkar who called aerial imagery for agriculture a “big white space opportunity.” The challenge is convincing farmers that he can offer them unique value and a return on investment.

“There have been companies for the last 10 to 20 years that try and do stuff with drones and manned aircraft to provide aerial imagery for agriculture, but no one has been successful because they haven’t taken imagery beyond a pretty picture,” he says. “There’s a lot of snake oil out there. So, we deal with that by showing our third-party university trial data that validates the power and accuracy of what we are doing.”

Cutting through the static around ag data is another challenge for any company entering the farm management and decision support space. Although there are only few startups offering aerial imagery for agriculture, like TerrAvion that recently raised a $10 million Series A, farmers are finding themselves inundated with data from many agtech providers.

“There is information overload in the industry, but we offer a variety of training and interpretation support features with our team of agronomists either in person or over the phone [to help farmers grapple with it],” explains Madgavkar. “To make the data sticky, we find that around an hour of training upfront on the basics of what imagery layers mean and how to interpret them makes a huge difference for farmers’ adoption and engagement levels.”

After the initial training, users can contact Ceres at any time for additional support.

Future plans

Although Ceres is steadfastly focused on the agriculture market, which it describes as a $20 billion global opportunity, it has already considered applying its technology to forestry, livestock management, oil and gas infrastructure, urban applications, and any type of natural resource.

“Our approach has been similar to Tesla: start with the high-end, niche market. We started with high-value crops like orchards and vineyards. Now, we want to take the product more mainstream.”

“In five years, we see this as becoming a tool that every farmer can use,” he says. “In the next 10 years, we want it to be used more broadly as a resource optimization technology.”