Weather. It’s either a farmer’s best friend or greatest foe depending on how Mother Nature’s meteorological temperament unfolds from season-to-season or even month-to-month. Sometimes we sound a bit like Goldilocks when asked to opine on how we’re getting along with the forecast. One week the rain might come too heavy but the next we might tell you that it’s been much to dry.

It’s not borne out of pickiness or a lack of adaptability. There are simply specific times in each season where certain weather patterns are highly desirable while, more importantly, others can be so disastrous for our success that we are reluctant to say them out loud.

In 2019, Mother Nature threw US producers a few relentless and unforgiving weather events causing some serious upset among growers. You only needed to look at social media during planting and harvest to see how deeply some were affected. Images abounded of semi-trucks swept off roads by fast-moving water, cattle stranded in rivers, the wrong crops still in the ground well into December, and messages from local municipalities inundated social media as farmers impacted by weather events took to social media share and commiserate in the impact.

As if the flooding wasn’t enough, an early freeze threatened crop maturity throughout the Midwest. Social media once again was set ablaze by forewarnings of devastating lows to come. Numerous maps of the areas that would be most impacted peppered social media feeds while farmers were left largely defenseless against the unseasonably early weather event.

We asked Indigo to pull some data using its GeoInnovation platform to tell the story of weather events in US corn this year and the impact they had.

First came the floods

The first major weather event involved historic rainfall in the spring that caused severe flooding throughout the Midwest and key areas for crop production.

Corn and soybean producers battled nearly 2,000 flooded acres in March and still reported 1,000 flooded acres by the end of May. This severely waylayed farmers’ planting plans, forcing them to delay planting until uncharacteristically late while they waited for waterlogged fields to drain.

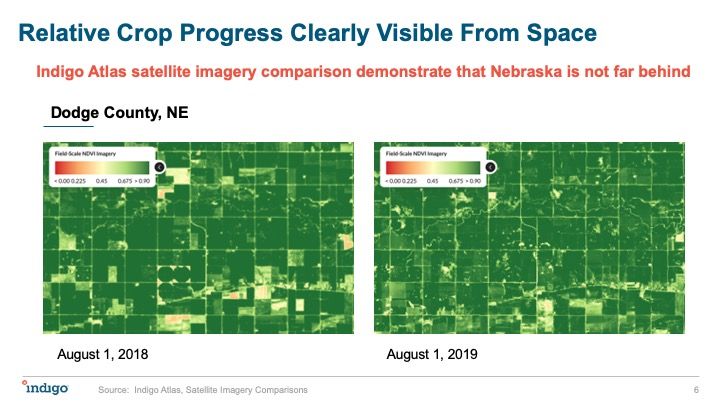

As a result of the delayed planting, the US corn crop failed to reach its average target, according to Indigo’s crop health index, which is a proprietary measure of plant vigor developed by Indigo based upon satellite imagery data. Around August 19, the US corn crop typically reaches a peak health index above 0.6. This year, however, it peaked toward the end of August at roughly 0.55.

“We had a wet spring, leading to planting delays almost everywhere. It was like a race, and the runner got a slow start out of the blocks,” Barclay Rogers, VP business development, GeoInnovation, at Indigo told AFN. “The crop (corn) was making some progress in certain places like Nebraska, similar to a sprinting runner on the backstretch. Unfortunately, the progress was cut short with the early freeze – like the race official called time before the runner got a chance to get fully to the finish line.”

The flooding had a varying impact on different areas of the Midwest, America’s corn belt. Ohio suffered worse consequences than Nebraska, according to Indigo data, with the Ohio corn crop falling well behind its normal five-year average yield of 163 bushels per acre. Indigo estimates the average for 2019 will be 139 bushels per acre.

The Nebraska corn crop managed to catch up, however, reaching a 2019 estimate of 189 bushels per acre, which is slightly above the five-year average of 183.

Pricing reprieve

Corn producers received a bit of a reprieve from the challenging planting season due to an improved basis price (the difference between the futures price and a local cash price) for corn.

“Changes in logistics due to a large number of late-planted and delayed-planted acres led to much better than normal basis numbers in many areas. This has firmed cash prices despite heavy downward pressure in the futures market,” Rodney Connor, senior director global markets intelligence and analysis at Indigo, told AFN.

“While many growers are not excited about current cash prices, anyone with hedges on, or those that understand how to use basis contracts, have been pleasantly surprised with better-than-historical prices. This year appears to be unique because those basis disruptions are encouraging grain to be hauled farther and sometimes in completely different directions than we are used to.”

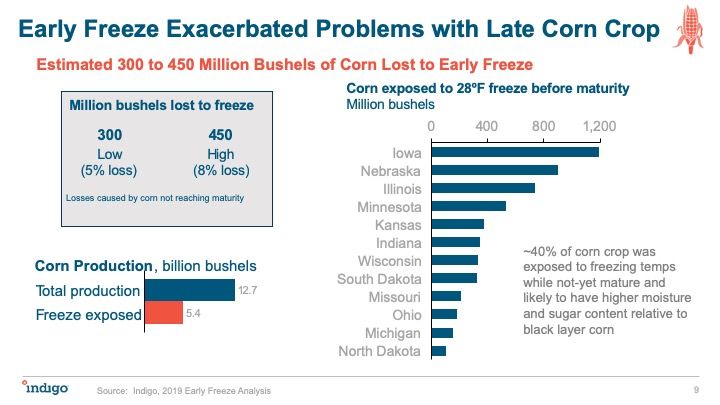

The early freeze

Improved prices could have softened the early-season weather challenges, but an early freeze hit a late-maturing, waterlogged corn crop in mid-October. Temperatures below 32°F for a few hours or near 28°F for a few minutes can impact the quality of the grain. The early Fall frost exacerbated the corn crop’s existing challenges, with Indigo estimating that 300 to 450 million bushels of corn were lost due to the early freeze. Iowa felt the biggest chill, with an estimated 1,200 million bushels exposed to a 28°F low, with Nebraska, Illinois, and Minnesota following behind. Overall, 40% of the corn crop was exposed to a freezing temperature while unmatured.

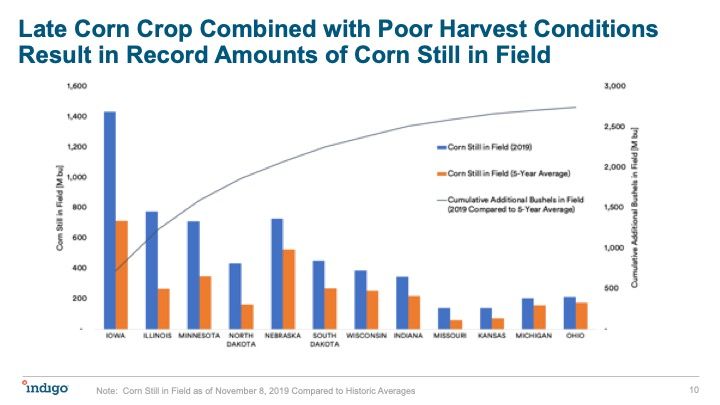

As a result of 2019’s one-two weather punch, record amounts of corn were still in the field in mid-November throughout the US, particularly in Iowa where 1,400 bushels remained. In Illinois, Minnesota, and Nebraska farmers had roughly 700 bushels each left behind at the same time.

“The late-maturing crop combined with the early frost hit many places hard — we still had record amounts of corn in the field as of early November. Farmers continue to push to get that crop in and dried down. Markets will be paying close attention to the effects of this late-harvested corn on overall supply,” explained Rogers.

Could tech have made a difference?

Surprise weather years like this are hard for farmers to predict. Even weather forecasting tools can only go so far. But what technological tools can do is help farmers to stay on top of what the impact of that weather could be on their farm, especially if analytical models can be continuously updated.

“The departure from normal that the weather gave us this year is a showcase for why we want to have this continuous streaming of data continuously refining an estimate of what is going on and what to do about it,” Eric Taipale, CEO of drone data analytics startup Sentera (an AgFunder portfolio company), tells AFN. “Most agronomic advice is based on regression to mean 30-year models, so the closer things like weather track to those 30-year averages, the more correct the models are. And, of course, this year was nothing like that. For Sentera, we are taking data updates along the way. A departure from normal is a showcase for why we want to have this continuous streaming of data continuously refining an estimate of what is going on and what to do about it.”

Due to the enormity of weather’s impact on farming operations, it’s no surprise that several agtech startups have developed tools specifically for weather prediction. aWhere was an early player in the advanced weather prediction space, launching in 1999 to provide daily, localized, agronomic weather support as well as Climate Corp’s weather-based insurance product which it later sold to Monsanto. France’s Sencrop raised $10 million in a Series A round earlier this year to expand its agro-weather station network, for example, while Sweden-based Ignitia offers tropical weather forecasting primarily for smallholder farmers in regions like Mali, Ghana, and Nigeria. Skymet offers a weather forecasting service for producers in India, too.

Monsanto-backed Understory analyzes and processes data to create real-time weather forecasting based on historical, current, and estimated future conditions. It claims to offer a new type of weather data because its sensors analyze conditions directly at the earth’s surface, compared to traditional, radar-enabled weather stations that collect data from the atmosphere.

Some startups like UK-based Cervest are even starting to dabble in the emerging climate modeling-as-a-service space to help businesses combat increasingly unpredictable weather patterns.

Even if a tool can predict the weather, however, a farmer still has to figure out how to combat or prevent against a disastrous impact. Once a crop is in the ground, for example, a farmer is limited in what she can do to protect it from an early freeze.

This is where seed trait technology may help farmers see a kernel of difference in terms of weather tolerability. Startups like Seed-X are using seed trait technologies are hoping to create new varieties that can better withstand extreme conditions like drought. Caribou Biosciences, founded by the scientist largely attributed with discovering CRISPR gene editing, is researching whether CRISPR can be used to promote drought tolerance and overall healthier crops. And Benson Hill Biosystems recently acquired Iowa-based eMerge Genetics, known for its high-yield, high-protein non-GMO soybean varieties.

Precision Biosciences’ food-focused subsidiary Elo Life Systems, which is developing food crops with nutritionally-improved characteristics via its ARCUS technology system; and Israeli computational biology startup Equinom, which is breeding crops with improved characteristics without any genetic manipulation, have both raised funding from venture capital.

Whether these companies can find ways to make plants more resilient to things like flooding and early freezes could become a major market opportunity if farmers continue to face wild weather years like 2019 in the future.

Inari is taking a slightly different approach to rethinking its approach to seeds by focusing on expanding global seed diversity. It believes its technology is unique in that it enables the company to uncover the enormous and largely untapped potential of seeds’ natural diversity, helping to reverse seed industry practices of the last 150 years, which have largely focused on increasing yield only. Inari closed an $89 million Series C in August.

“Farming is difficult; you’ve got so many things coming at you and it’s hard to figure out the best option given the challenges of a particular growing season. Technological innovations — ranging from better seed treatments to improved crop marketing tools with many things in between — aim to help farmers manage their risks,” says Rogers. “In this particular season, it may have been hard to do much about the delayed planting. But, by keeping a close eye on regional crop performance, a farmer could have gleaned insights into anticipated basis price movements to inform his crop marketing decisions.”

For some farmers, labor is a major challenge. If a serious weather event threatens a crop, he or she may decide to take quick action but this may be hindered by a lack of available workers to get the job done before damage sets in. Farm robotics is a steadily emerging area that hopes to address labor concerns for farmers.

Raven Industries recently acquired driverless tractor startup Smart Ag as well as autonomous farm equipment manufacturer Dot Technology Corp. Bear Flag Robotics is hoping to automate common tasks on the farm to free up the farmer’s time, while Yamaha-backed Invert Robotics is developing a climbing robot that can inspect hard-to-reach areas.

And a small group of startups is even trying to help farmers hedge their bets better when it comes to marketing their crops.

“There are entire customer bases of ours that just didn’t even have any expected crop for the year. That’s not good,” Jake Joraanstad, co-founder and CEO of grain marketing platform provider Bushel, told AFN. “A lot of grain companies are about volume. If corn is sitting in the field, they aren’t getting volume. It’s possible that some of the corn can be harvested in the Spring, but the quality goes down.”

Other players in the digital grain marketing space include Indigo’s Grain Marketplace, FBN’s Online Grain Trading Tool, FarmLead’s Monsanto-backed Online Grain Marketplace, and FarmLogs’ AutoHedge App.