Biologics hold substantial promise for a more sustainable food system, but with millions of microbes to sort through, startups are turning to partnerships to hunt for the most promising strains in the bacterial haystack.

The bio inputs space is on a rapid climb as farmers are looking for new solutions instead of the traditional suite of chemicals that they’ve relied on for the last several decades. This new category of products includes natural crop protection and plant health solutions that can be used alone or in conjunction with a traditional chemical input program. At their core, they consist of specific microbes that have been proven to provide certain benefits to a plant, whether it’s helping them uptake nitrogen from the soil or helping the plant fend off pests and disease directly or through the indirect production of metabolites.

There are a number of forces driving farmers to consider bio-based solutions even if they remain skeptical about their consistency and efficacy. Environmental issues like the unintentional creation of herbicide-resistant weeds and a dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico due to fertilizer runoff carried down the Mississippi River from Midwest crop country are just a few examples. Human health concerns regarding some of the chemical inputs that are used in food production are also reaching new heights as Monsanto continues to fight battles in court regarding glyphosate and its link to cancer.

Joyn Bio and NewLeaf Partner on Research

While the biotechnology space is often fraught with competition and clandestine secrets that could unlock major progress – and profits – some startups in the biologics space are starting to see that the only way to make headway through these millions of microbes is by joining forces.

“There are literally millions of different kinds of microbes that grow naturally. The challenge is how you make this huge number of microbes that interact with many plants and environments and that have a role in controlling plant disease and health traceable?” Tom Laurita, CEO and co-founder of NewLeaf Symbiotics, tells AFN. Laurita has just announced a partnership with Joyn Bio, the $100 million joint venture between Bayer Crop Science and microbe manufacturer Ginkgo Bioworks.

Under the partnership, Joyn Bio will have access to NewLeaf’s library of proprietary, highly- characterized strains of plant-colonizing microbes that it’s been building since 2012. This will get Joyn’s flagship nitrogen-fixing microbe on the market two to three years earlier than previously scheduled. The partnership is valued at around $75 million.

“Joyn will have an exclusive license to leverage select NewLeaf microbes for developing novel solutions that deliver a range of important benefits to plants, including nitrogen-fixation and crop protection capabilities. NewLeaf will receive an upfront payment and payments for achieved milestones throughout the agreement term,” reads the press release.

Joyn Bio touts exclusive access to the genetic codebase and biological engineering foundries of Ginkgo Bioworks, which is focused on genetically engineering microbes for partner companies in the flavor, fragrance, agriculture, and food industries. Joyn Bio is engineering these microbes with the hopes of offering novel disease and pest control products to farmers so that they can reduce their reliance on traditional chemicals.

The two businesses will continue to market their own products with the key differentiator being that NewLeaf focuses on naturally-occurring microbes, while Joyn registers, markets and sells engineered solutions.

“A big deal in the biologics space”

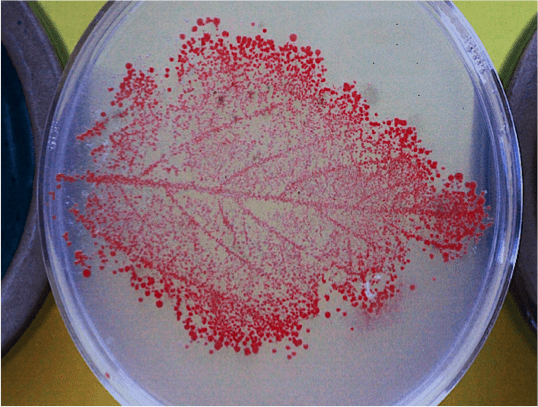

NewLeaf describes itself as having deep expertise and IP in genomics and production thanks to its platform, the Prescriptive Biologics Knowledgebase, which combines nature and machine learning. This computational engine curates genotype and phenotype data and predicts the performance of microbes from the NewLeaf’s library. For the last eight years, NewLeaf has been focused on a specific family of microbes called M-trophs, with 12,000 strands in its genomic library.

“The engineering approach that Joyn Bio has taken is extremely promising. What they do has always been something we have recognized as a revolutionary opportunity in agriculture,” Laurita explains. “It’s important to understand the value of Ginkgo Bioworks. Its technology brings an extremely efficient method of assaying engineered microbes and that’s something we don’t have and that we can’t build.”

For Joyn Bio, having access to the library of M-trophs and being able to understand which strains have the most potential as crop inputs is just as valuable.

“This partnership gives Joyn Bio access to these highly characterized M-trophs that NewLeaf has spent so much time developing. It’s great for us to get access to these as host or chassis microbes and it gives NewLeaf the opportunity to see if their host microbes are going to be useful,” Mike Miille, Joyn Bio CEO, also told AFN.

With NewLeaf focused on naturally-occurring microbes and Joyn Bio focused on engineering microbes to optimize performance, one may think that the partnership is an unlikely pairing. But considering the size of the market opportunity and regulatory roadblocks that could develop in certain regions opposed to genetic engineering, the duo is really just covering all the bases.

“Each company has a clearly defined role. This is a big deal in the biologics space. We are two of the most science-based, serious, forward-working, and well-financed companies in the space. The fact that we are joining together is really quite a statement in the industry,” Laurita says.

Regulation & Social License for GM Microbes

Certain markets in Europe and other geographies that instituted outright bans on the cultivation of GMOs may take a similar approach to genetically engineered microbes, for example, leaving the door wide open for products based on naturally occurring microbes. And in some cases, the natural product may be better suited for the task, Miille believes.

“There are plenty of targets out there and some may be best handled with a naturally occurring microbe that evolved to do something with the plant, and in other cases, the natural product probably won’t be as effective as the engineered microbe. I see room for both of these approaches in the market and that’s another reason we are working with Joyn Bio,” Laurita adds. “They can do things we won’t and we will do things that they won’t.”

There is, of course, the other task of obtaining social license as well. If the GMO era has taught biotechnologists and entrepreneurs anything, it’s that a lack of public approval can have a damning effect regardless of the technology’s proven potential in the lab.

With so much current attention around the importance of gut health and the role of the microbiome in human health, however, parlaying the potential benefits of manipulating microbes for crop health could be a natural and logical leap for many consumers. But as Miille points out, any time a genetically engineered product nears the market, it’s best to take a proactive as opposed to a reactive approach.

“You have to assume there are going to be challenges and people who are anti-GMO that will be anti-anything. The best way to address this challenge is through education and communication and by making people aware that you have done all of the safety studies and that you can articulate the benefits of what you are bringing to market at an emotional level versus arguing about the science,” he explains. “We have learned that you have to start now – three or four years before the product comes out – to get people comfortable with the concept.”

For genetically engineered microbial crop inputs, therefore, the bar is set as high as it gets. Not only do companies aiming for commercialization have to quell any consumer misgivings, they must also prove themselves as effective as traditional chemical inputs when it comes to fighting disease and pest pressure or boosting yield.

“That’s a big challenge,” Miille says, “We have to demonstrate how much an engineered microbe can work relative to a natural microbe. The target we gave ourselves is that if these are for pest or disease control, we want those microbial products to work at the same level or even better than the current chemical standard. It’s not good enough to say that we want to work as well as the natural biologic products. We have to set a much higher target.”

Biologics Partnerships on the Rise to Meet Challenges

After getting through the challenge of researching and discovering the best microbes for the job, getting them into farmers’ hands is another major headwind for these groups. Farmers have been skeptical about biologics and their efficacy.

“Partnerships are increasing among biological companies. This trend will continue,” Pam Marrone, CEO and founder of Marrone Bio Innovations and a veteran in the biologics space, wrote to AFN. “There is a new crop of startup companies that have enabling technologies such as formulation technology to increase the efficacy of biologicals and we have several collaborations in this arena. We also just announced a collaboration with Valagro on new biostimulants. A small company like ours can’t do everything so small companies can leverage each others’ technologies to joint benefit.”

Breaking down many farmers’ initial skepticism over whether microbes can work just as well as chemicals is oftentimes the first and most challenging step. The production cycle in commodity crop agriculture is a limiting factor, where farmers only have one opportunity each season to trial new products. With farm profits as slim as ever, risking this year’s income on an entirely new class of input is a big ask.

There are also the classic set of challenges that has faced every bio-based inputs company, including how to mass-produce a temperature-sensitive, living bacterial product while achieving the same level of consistency and efficacy that farmers have grown accustomed to in traditional chemical inputs. Many of NewLeaf’s patents focus on these downstream obstacles surrounding production, Laurita explains.

3Bar and microbial input startup Pivot Bio have also partnered recently to try and solve some of these challenges. Pivot Bio has developed a nitrogen-producing microbial product called PROVEN that fixates nitrogen from the atmosphere and secretes it at the corn crop’s root zone to be used when the plant needs it. But perhaps more important than the science involved is the packaging and delivery mechanism of these microbes, which 3Bar provides; chief complaints from farmers about biologics include integrating the products with existing equipment and programs as well as efficacy, and inconsistent results.

3Bar’s delivery system allows a farmer to cultivate a fresh batch of microbes right on the farm or at home by pushing a button on the outside of the box, starting the bacterial fermentation process. Everything the microbes need to grow is located inside and the farmer does not have to perform any contamination protocols like sanitizing his or her hands before starting the process. Within 24-48 hours, the microbes are ready for use but they can be kept inside the box for up to three weeks. This is a key window for farmers who may have a sudden change of plans due to on-farm emergencies or a sudden unpredicted change in the weather.