Vertical farming has long been scolded for acting too much like a Silicon Valley SaaS industry and not enough like an agricultural one. This week’s news of Plenty‘s bankruptcy—the latest of many—hit that point home harder than most.

One criticism frequently leveled at the much-maligned sector is that it applied the rapid-growth, rapid-returns Silicon Valley ethos to one of the most complex life forms out there: plants.

Former Plenty CEO Matt Barnard illustrated that ethos this in a 2017 interview with AgFunderNews:

“We are developing multiple farms, we have literally dozens of farms in different stages of development in different parts of the world right now. Several of those will open in 2018 and then the rest are slated for 2019 and beyond. We’re going to be working to get these farms out so that we can get food into the homes and hands and mouths of people as quickly as possible.”

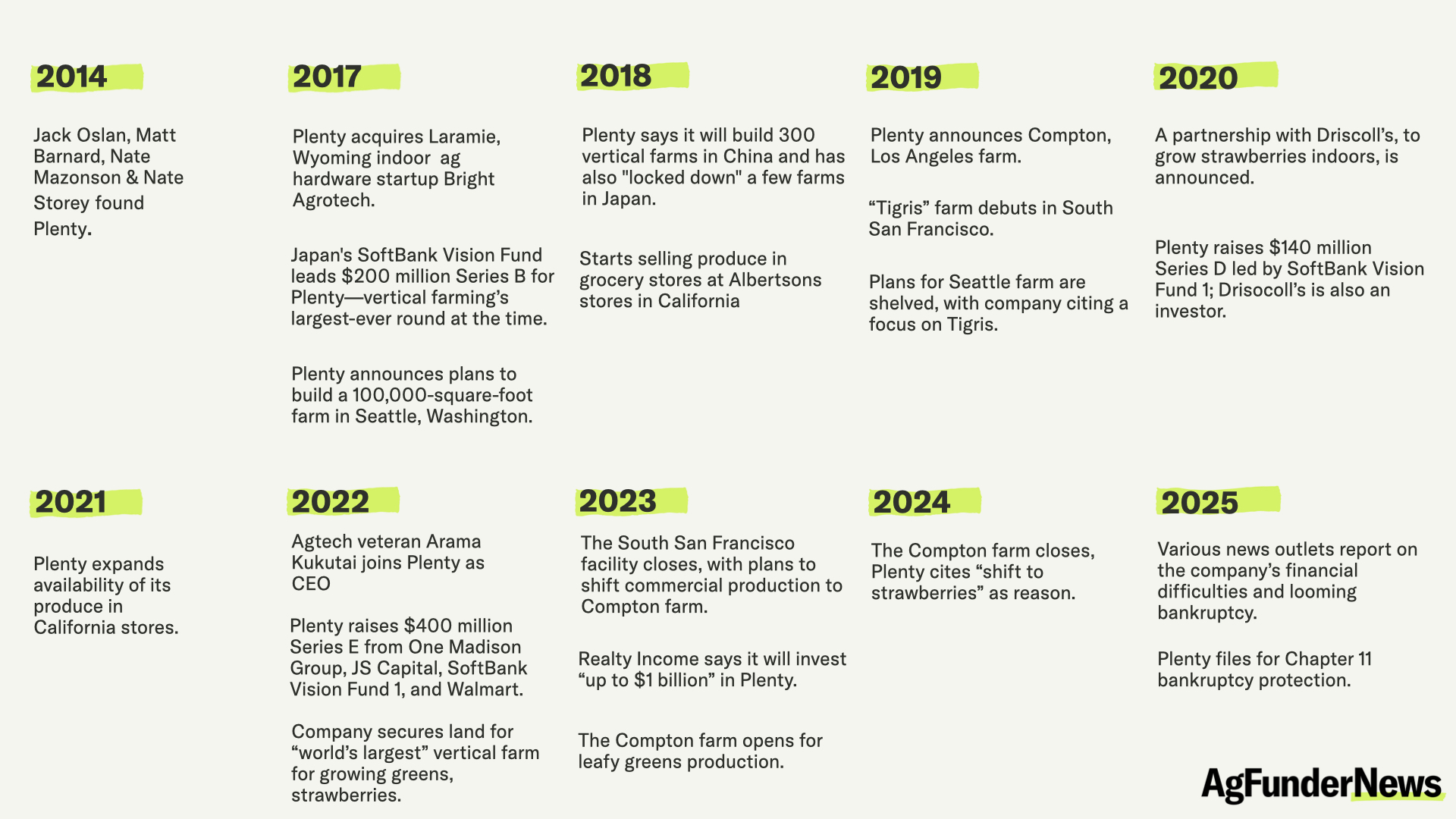

As countless news reports this week highlight, none of that actually happened. The few farms Plenty opened since 2017 are mostly gone, Barnard long ago moved on to other ventures, as did investor-CEO Arama Kukutai, and Plenty announced on Monday it had filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection.

Barnard did not respond to a request from AgFunderNews to comment.

“To appeal to investors, [many vertical farming companies] put together business plans and financial models that in hindsight were unachievable,” EchoTech Capital managing director and former Citi banker Adam Bergman tells AgFunderNews.

“Plenty raised roughly $1 billion dollars, and today they have only one strawberry farm operating, and that only just is scaling up,” he adds. “The return to Plenty’s investors on $1 billion of capital is not going to get future investors excited about vertical farming.”

One quick glance at Plenty’s last 10 years highlight this point:

‘Biology doesn’t care how much funding you’ve raised’

“Plenty always struck me as the most ‘Silicon Valley’ vertical farming company out there,” says Agritecture CEO and indoor agriculture expert Henry Gordon-Smith.

“You can see it in everything—from the headquarters location to the Bezos backing to the way the leadership talks. There was a lot of big, bold language about revolutionizing food.”

Such talk plays well with investors, he adds, but it’s useless currency in agriculture.

“Biology doesn’t care how much funding you’ve raised. Things take time—and you can’t just code your way around that.”

To be fair, Plenty wasn’t the only one using “big bold talk” to woo investors—it was practically endemic in vertical farming for years.

“It was part of the game,” agrees Gordon-Smith. But, he adds, Plenty took it to new heights. “They were talking about growing watermelons and fruit trees indoors. I mean, yeah, technically you can, but economically? Not even close—definitely not at scale, and not anytime soon.

“It started to feel less about improving the food system and more about inflating the valuation,” he adds.

‘Plenty lost something important along the way’

When Plenty acquired Bright Agrotech in 2017, it latched onto a major differentiator.

“It was a game-changer early on, and [Bright Agrotech] cofounder Nate Storey brought something most vertical farming startups didn’t have: a real farmer’s perspective,” he says.

Storey, who founded Bright Agrotech as a graduate student, brought a background in both crop science and agronomy, two areas of expertise any outdoor farmer would say are necessary for survival.

Gordon-Smith is well known for his view that vertical farming companies without a farmer, or at least someone with a farming background, aren’t likely to succeed.

“When Plenty started ramping up the hype, I was surprised [Storey] was still around. Then I heard he was on ‘sabbatical’, and his email just stopped working. That was a moment for me. When the top farmer at the company suddenly disappears, it usually means the direction has shifted—and not in a good way.”

According to Gordon-Smith, Plenty employees were looking for job openings elsewhere, saying the company had become more about raising money than anything else, and no one listened to the farmers anymore.

“That’s when it really clicked,” he says. “You can’t build a lasting agricultural company if the people growing the crops don’t have a voice. Plenty lost something along the way.”

Storey did not respond to a request for comment from AgFunderNews. His LinkedIn profile claims he is still on the board of Plenty, but it is unclear if this information is up to date.

Plenty has ‘an opportunity to succeed’

For his part, Bergman doesn’t believe the bankruptcy is the nail in the coffin for Plenty, or vertical farming. Though that’s not to say the company will have it easy in the near term.

“It’s going to come out of bankruptcy, and continue scaling up production at its strawberry farm,” he says. “I do believe Plenty has an opportunity to succeed.”

At the same time, Plenty is doing this with new technologies and production processes, and as a result will “face unexpected issues and find it difficult to stay on the projected timeline,” he predicts.

A spokesperson for Plenty highlighted the company’s work in strawberries, which is ongoing: “After evaluating all of our strategic alternatives, we have determined that pursuing a restructuring process is in the best interests of Plenty and all of our stakeholders. Through this process, Plenty will be better positioned to continue working toward our mission to make fresh food accessible to everyone, starting with the year-round production of premium strawberries in our innovative vertical farm in Virginia.”

Bergman is optimistic about the company’s prospects with strawberry farming—at least as long as Plenty has the Driscoll’s partnership.

“Driscoll’s has a bunch of berries that are incredibly tasty, but they can’t grow them outdoors and get them to market with a long enough shelf-life to appeal to consumers,” he says.

“In the long-term, I am optimistic that with the support of Driscoll’s, the global berry leader, Plenty will be able to grow some of the best strawberries in the world at its Virginia facility.”