Rudi Ariaans is co-founder and CEO, and Ferdinand Los is co-founder and chief scientific officer, at Hudson River Biotechnology, Wageningen, the Netherlands. The views expressed in this guest article are the authors’ own and do not necessarily represent those of AFN.

Our global output in agriculture has grown to an astounding 3 billion metric tons of crops – which has been mirrored by the inputs needed. Last year alone, we used 187 million metric tons of fertilizers, of which 70% was wasted and either ran off to underground waters or volatilized into the atmosphere. At the same time, 4 million metric tons of pesticides were applied, and agriculture accounted for 70% of the freshwater used globally. Tellingly, agriculture is now responsible for 24% of global greenhouse emissions.

An even more ominous figure was captured by a recent study by scientists from Cornell, Maryland, and Stanford universities, which found that global agricultural productivity has declined by about 21% in the last 60 years as a result of climate change. Add to that the expected population growth over the next decades, and you begin to undertsand that even with the improvements in yields we have seen over the last few decades, breeders cannot continue to guarantee production for all people. That’s why we need gamechangers in the form of novel methods and technologies that can help us – in consumption patterns, farming techniques, and biotech innovation.

Is the EU’s Farm to Fork Strategy realistic to increase sustainable food systems?

In the EU, the European Commission has pledged itself to the Farm to Fork Strategy, which is centered on organic farming. In this approach, 25% of the EU’s agricultural land will be used for organic farming by 2030. And while the European Commission acknowledges that innovations in areas like biotechnology can play an important role, regulation around novel genomic techniques is still restrictive.

Organic farming can definitely contribute to sustainability, but negative indirect effects such as additional land use needed for this method of farming are often overlooked. An organic farm will have an approximately 50% lower yield in comparison to non-organic farming. A massive transition to organic farming will decrease the pressure on our ecosystems in Europe, but can have substantial negative spill-over effects. Already we see that approximately 16% of global deforestation is linked to consumption in the EU.

As organic farming has a lower yield than non-organic farming, we would need almost twice as much arable land to grow the same amount of food. If we do not tackle this issue, the Farm to Fork Strategy may actually result in less sustainable, rather than more sustainable, food systems.

CRISPR will help us develop the varieties we need more quickly and efficiently

Novel breeding techniques have been instrumental in maximizing agricultural productivity, profitability, and sustainability. The technique that has generated most publicity — culminating in a Nobel Prize in Chemistry for Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna — is CRISPR, which scientists can use to adjust or rewrite DNA in a highly precise manner.

These edits are based on research that has been going on for decades to understand the molecular processes underlying genetic traits. Where these kinds of adjustments would traditionally take between seven and 10 years (if possible at all), they can now be done within two to four years. Owing to this, CRISPR has revolutionized how we can breed plants and make our food systems sustainable in the face of climate change and population growth.

EU to launch carbon farming framework by end-2021 following two-year study – read more here

An example is speeding up the development of varieties that need less fertilizer, water, or pesticides due to the targeted editing of traits. Taking into account we need these new varieties to decrease the pressure on our natural ecosystems while maintaining food security, the most obvious step to reach the goals in a reasonable timeframe, using an available technology, is CRISPR.

The key strength of CRISPR-based breeding is that it allows for faster and more targeted development of crop varieties. After several years of development, CRISPR is a technology mature enough to deliver today the plants that we need for the future, in a safer and more controlled manner than other approved genetic modification (GM) approaches such as mutagenesis.

As organic farming prohibits the use of synthetic pesticides, we urgently need to develop varieties that are hardier and less prone to pests and pathogens. And because organic farming generally uses more land for the same yield, we urgently need crop varieties with higher yields, to limit the additional arable land we need.

Additionally, these new varieties could decrease water, land, and chemical use in traditional, non-‘organic’ farming practices, too. But our traditional breeding approaches will not get us there in time, and CRISPR offers us the chance to accelerate the development of new varieties. Only with CRISPR can we generate crop varieties that would meet sustainability demands from organic and non-organic farming within the timeframe needed.

So it’s a clear win-win, right?

EU says no

Unfortunately, not. For this innovative tandem of organic farming and innovative biotechnology we require legislative change in the EU.

While the rest of the world is rapidly adopting CRISPR technology and solving these issues, the European Court of Justice ruled in 2018 that organisms altered by means of site-directed mutagenesis, like CRISPR, are included in the EU’s definition of a genetically modified organism (GMO.)

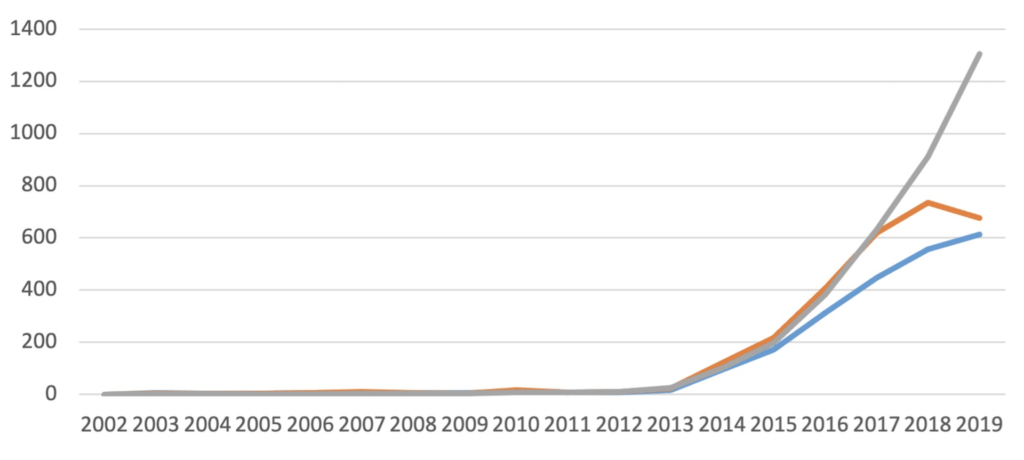

The implications of this ruling continue to be felt today, as it means the size or type of alteration to the genetic material is irrelevant. If there is mutagenesis — random or directed, big or small — the organism is legally deemed a GMO, and commercializing it on the European market is effectively impossible. This leaves the EU in a vulnerable position, in two ways. The first is the competitive angle, as over the last years, the number of patent applications has skewed enormously towards markets that have regulation in place that accommodates CRISPR and related techniques (see chart below.) More and more companies have moved their research and development elsewhere, leading to a brain drain of the best European talent and a lack of funding for research.

The second angle is sustainability. A recent report by the European Commission concluded that techniques such as CRISPR have the potential to contribute to sustainable agrifood systems in line with the objectives of the European Green Deal and Farm to Fork Strategy.

What’s more, a recent article in the journal Trends in Plant Science suggested that specific characteristics of organic farming may actually jeopardize the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that focus on climate action, life on land, and the elimination of hunger. This is mainly because massive adoption of organic farming would include negative indirect effects stemming from additional land use. A combination of organic farming and agricultural biotechnology, however, can mitigate these effects (see table below.)

| SDG number | SDG name | Expected benefits for SDGS resulting from combination of organic farming with agricultural biotechnology |

| 2 | Zero Hunger |

|

| 13 | Climate Action |

|

| 15 | Life On Land |

|

Clearly, the unavailability of edited products in the EU will expand beyond the fact that EU citizens might not be able to access the most nutritious varieties. Failing to embrace the best new varieties with traits that enable us to be more productive within organic farming will directly and negatively impact the move towards more sustainable food production globally.

Let’s go for the Norwegian model

Even though the recent study regarding the status of new genomic techniques under EU law was positive on the potential benefits of CRISPR, changing EU-wide regulations will take several years and will be very complex. Additionally, there is still quite some resistance from NGOs and organic farming associations that could hamper the adoption of new legislation.

An analogy that comes to mind is that these actors would have liked us to keep travelling in horse-drawn carriages as they are safer than motor cars. But cars are now widely available to us, and they are faster and will allow us to get where we need to go in a much shorter time. So instead of spending EU R&D funding on existing, slower breeding techniques, why don’t we research how to improve the latest technology, to make it safer and properly regulated, so that finally the consumer can trust and adopt it? To keep with our analogy: we should fund the technologies that facilitate the transition towards universal and sustainable use of cars, instead of trying to improve the aerodynamics of the carriage.

To avoid permanently losing the both the sustainability and the innovation race, we need to untie our hands at short notice. For that, we take inspiration from Norway.

The Norwegian Biotechnology Advisory Board recently proposed a new model which makes a distinction between three tiers within GMOs (see table below; sourced from Bratlie et al, EMBO Reports.) Tier 1 genomic edits should be allowed for commercialization under GM regulation but without the needed of approval from EU authorities. Only notification from the producer should be needed.

| Exempted from regulation | Covered by GMO regulation | ||

| Tier 1 | Tier 2 | Tier 3 | |

| Organisms with temporary, non-heritable changes | Genetically engineered organisms with changes that exist or can arise naturally and can be achieved using conventional breeding methods | Organisms with other species-specific genetic changes | Organisms with genetic changes that cross species barriers or involve synthetic (artificial) DNA sequences |

| N/A | Notification (confirmation required) | Expedited assessment and approval | Standard assessment and approval (current requirements) |

Making this exemption under existing GMO laws will allow this change to be relatively quick, and offers a number of benefits:

- Provides a chance for our food systems to tackle the ambitious goals set by the Green Deal and Farm to Fork Fork initiatives;

- Enables the transition to organic farming to be sustainable;

- Allows EU funding to flow back to EU players involved in developing the CRISPR toolbox;

- Compels scientists and companies located in Europe to stay here;

- Lets breeding companies (global and European) begin adoption of CRISPR technology in their product development pipelines;

- Helps EU companies to stay competitive with US and Chinese companies that have already implemented CRISPR technology;

- Prevents an illegal flood of untraceable edited products from countries in which Tier 1 products are not required to be labelled as GM.

We all agree the urgent need to decrease the strain on our natural ecosystems and keep food production up to par. Such a challenge can only be tackled by developing new crop varieties within a reasonable time frame; that is, within the next 10 years. Only with best technology available — CRISPR — in the farmer’s toolbox will it be possible to achieve the EU’s ambitious goals for sustainable food systems and prevent negative spillover to our global sustainability goals.