Editor’s Note: Eric Archambeau is co-founder and managing partner of Astanor Ventures, an impact investing venture capital firm investing in purpose-driven companies in the sustainable agri-food sector. Previously he was chairman of the Jamie Oliver Food Foundation, which was dedicated to bringing food education to schools and youth groups, businesses, and communities.

At first, we worried about the old, then the asthmatics and diabetics, then those with lung disease and transplant patients. As the lockdown bed in, pregnant women and people with immunosuppressive diseases were added to this list.

Weeks later the statistics told of the devastating impact on black, Asian, and ethnic minority groups.

Yet among the reports on the tragic and rising death toll, there’s one underlying health condition that has been largely overlooked: obesity.

Obesity and Covid-19: The numbers

One of the largest UK studies on the Covid-19 mortality rate to date, from Glasgow University, this week found that as a patient’s Body Mass Index (BMI) increases, so does their risk of having a severe case of the virus.

The Coronavirus Clinical Characterisation Consortium similarly found that a third of people admitted to hospital with Covid-19 die, and being obese – defined as when you have a body mass index (BMI) of 30 and higher – increases this risk by a staggering 37%.

To put that further into context, the obesity rate in the UK is 28.7% and in the US it’s an outstanding 39.6%. Furthermore, just 12% of Americans are deemed metabolically healthy, according to a recent AFN post.

Cause and effect

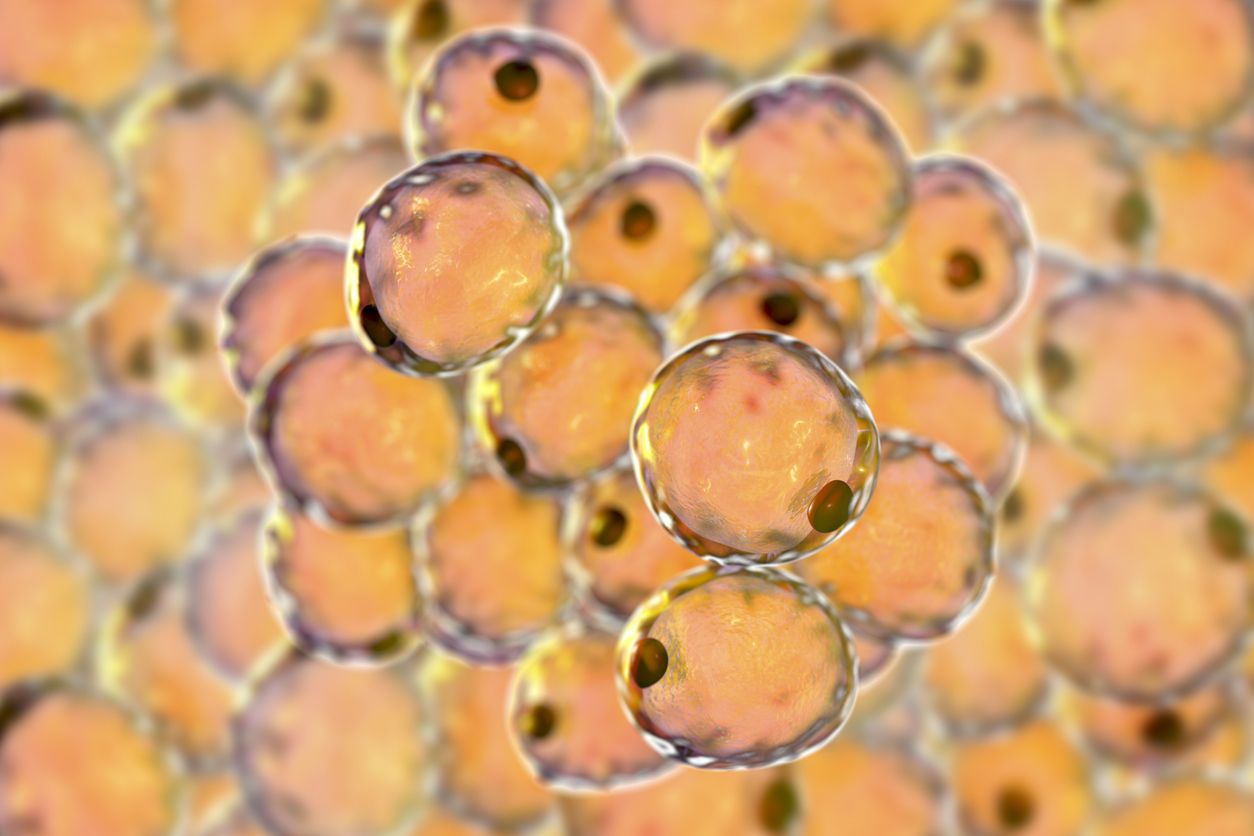

Obesity is a chronic inflammatory disease and it starts with an inflammation in adipose tissue, or body fat. Researchers have proposed there may be a link between this inflammation and an immune system response in Covid-19 patients called a “cytokine storm”.

This storm response has been seen in patients at the tail end of Covid-19 infections or once it has left their body, and has caused instances of thromboembolism – a deadly cardio-vascular event. It’s particularly common in overweight patients due to the already large reserves of cytokines in their adipose tissue.

Treating Covid-19 as a societal crisis

While many of these results are preliminary, it represents a clear message – the link between obesity and coronavirus cannot be ignored. We should revisit this pandemic as much of a societal crisis as a sanitary one; one that lies in the fundamental failings of global food systems.

For the past 70 years, our food systems have focused on reducing the costs of producing and distributing calories, but not the costs of nutrients. This combination of poor quality food, consumed in vast amounts, has fuelled our obesity epidemic. On the way, we have weakened the health of an increasingly large proportion of the population and put them at risk.

Financially disadvantaged populations are more prone to higher rates of obesity due to a lack of access to healthy food and food education. Western societies, with their reliance and penchant for high-sugar and high-fat foods, are particularly vulnerable. Leading cardiologists have suggested that UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson suffered worse than some of his “slimmer” cabinet members due to his increased weight and reported poor diet, high in refined sugar.

The bitter irony is that Sub-Saharan Africa has some of the lowest obesity rates globally – almost five times less than the Western world – and with a median age of its population at just 19.7 years, this has seemingly made it robust against the virus itself, with the fatality rate from the disease sitting at 2.5%, versus the world average of 6.9%.

Yet, the impact the virus is having on global trade, the supply chain, and on international aid has led the UN to estimate that the number of people facing acute hunger in such regions is set to double, to 265 million by the end of this year.

The role of agri-foodtech

Once the urgent medical care crisis has retreated, it will be time to reassess our agri-food system and how much importance we place on the sector. We must also look to tech to help us solve many of the problems that led us down this fatal path; tech like the decentralised distribution system developed by Paris’ La Ruche Qui Dit Oui, an Astanor portfolio company, which connects farmers of high-quality, ultra-fresh food directly with consumers across France, Germany, Spain, Italy and Belgium — all while passing on more than 80% of the sale price to the growers and their communities, enabling farmers to focus on quality rather than quantity. Tech like the UK-based communication platform WeFarm that inter-connects millions of small farmers in Africa together and with the buyers of their products, enabling the spread of regenerative farming best practices and fair compensation for those connected farmers.

Teak Origin, from Boston, another Astanor portfolio company, is revolutionising how we view the nutritional value of food via an AI-powered system that tells a consumer what a product is, where it’s from, how fresh and nutritious it is and how it compares to similar foods across the globe. All designed to help them make informed choices and give more transparency from farms to dinner tables. While Integrative Phenomics in Paris aims to provide medical and nutritional science-based nutrition plans, using lifestyle and gut microbiome profiles to give individuals tailored health goals such as weight loss or stress reduction. Then Good Idea, founded in the San Francisco area by the founders of Oatly, has developed a flavoured sparkling water that contains amino acids and chromium that, when paired with food, reduces sugar response level by 30% and the insulin load in the system, thus helping pre-diabetics to not cross the line that would put them even more at risk for the next Covid-19 wave.

These are just a handful of examples where tech can help stem the flow of poor-quality food and induced health problems, and unfair supply chains globally yet, despite accounting for up to 20% of GDP, last year the industry received just 6.7% of global VC funding. This has hindered innovation. A hindrance the coronavirus has brought starkly into the light.