Global eating habits have changed dramatically in the wake of the widening Covid-19 pandemic. With bars and restaurants shutting down as entire countries go into lockdown, the world’s retailers have been scrambling to meet surging demand at the supermarket or via delivery apps. Basic staples and canned food products are back in fashion, while certain health foods are flying off the shelves almost as quickly as toilet rolls.

But Covid-19 is impacting much more than the end of the supply chain; farmworkers, logistics suppliers and more are struggling to keep up and it’s impacting the supply of fresh produce and staples.

Here’s a look at the impact on pricing for a few food and ag products where we could find information, at the request of a few of our readers. (NB: due to the constantly changing dynamics of consumer demand, supply chain logistics, farmworker availability, and so on, these prices and movements are a constantly moving target.)

Want specific reporting related to Covid-19 in food & ag? Email us here.

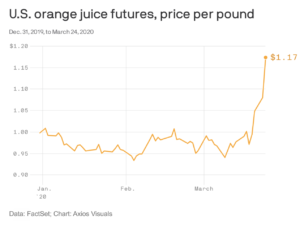

Spiked orange juice

I’ve been drinking a lot more orange juice these last few weeks after my nutritionist sister told me extra Vitamin C could help ward off Covid-19; a friend in China, where the outbreak first surfaced, also suggested to drink more of it. Clearly this isn’t a secret; retail demand for orange juice spiked 40% in the week ending March 14, causing orange juice futures to rocket, making the “usually sedate asset the best-performing commodity in the first quarter of 2020,” according to Wall Street Journal. Further fuelling demand are concerns about supply, with farmworkers potentially staying at home to avoid contagion from fellow citrus pickers, according to Jack Scoville of The PRICE Futures Group; traders are also pricing in expectations of a strong hurricane season impacting yields.

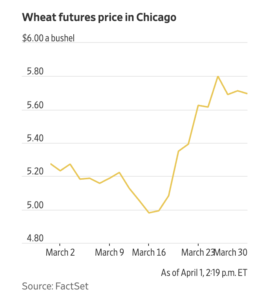

Staple speculation

Another clear anecdotal insight obvious to anyone visiting a supermarket is that consumers have been stockpiling dry, long-lasting foods like pasta and rice.

Combine that demand with disrupted supply chains — think truck driver and factory worker shortages — and restricted agricultural exports and the prices of wheat is also on a stark incline.

The price of wheat futures trading in Chicago, the global benchmark, has risen 15% since mid-March and reached as high as $5.72 a bushel Monday, bucking the coronavirus-induced economic downturn that has hurt most commodity markets especially fuel. Meanwhile, the price of a variety of Thai rice, a key benchmark for international trade, has jumped 17% to $490 a metric ton since the start of the year, according to the International Grains Council. Drought in Australia has put extra pressure on supply.

It could be quite a different story for some of ag’s biggest commodities, corn, soy, and sugar, however. Stable, a commodity price insurance platform, has flagged Covid-19’s drastic impact on the global energy market and the direct bearing that will have on many staples. “As the relationship between agricultural markets and crude prices has continued to grow stronger, a knock-on effect of oil prices could pressure agricultural markets,” the company commented in March. “Crude oil values are directly linked to those agricultural commodities used to produce biofuel; the demand for corn, soybeans, sugar and others used as a feedstock for biofuel is directly related to the price of the main substitute product crude oil.”

US farmers could be left with a glut of supply pushing down prices, however, much will depend on how effectively Latin American ports in Brazil and Argentina are able to function given the onset of the virus there. Trade restrictions are already mounting within these two huge agri-exporters, which could take a severe toll on markets. As an example, a major port in Argentina, Timbues, that along with two others in the Rosario region is responsible for 80% of Argentina’s primary and agricultural exports, including soybeans, oil, and meal, closed for a week as part of the country’s attempts to curb the spread of the virus.

Dairy deluge

Covid-19 has certainly caused a change in milk-buying habits. Headlines around oat milk demand were hard to miss as the shelf-stable dairy alternative appealed to consumers wanting to avoid repeat visits to the supermarket. A report Nielsen released on March 2 showed oat milk sales rising by 305.5% over a one-week period last month, topping the shelf-stable consumer packaged goods category.

But what about real milk and dairy?

Analysts suggest milk prices could fall as much as 20%, close to 2008 global financial crisis levels, according to AgWeb. While consumers are still buying milk and dairy products like butter and cheese at the supermarket, the drop in demand from restaurants and schools is impacting dairy farmers’ ability to sell an increasingly abundant supply of the white stuff. This has pushed many dairy producers in the US to start dumping milk, threatening to devastate dairy-producing regions but also the local environment. In India, milk consumption has dropped a staggering 25% due to the closure of hotels, restaurants, and roadside tea stalls, according to eDairyNews.

Garlic & ginger

Touted for their Covid-busting properties, garlic and ginger are also mostly grown in Asia where the coronavirus first appeared and impacted food supply. China supplies nearly 80% of the world’s garlic export market and 47% of the ginger market. Brazil, Thailand and Peru are other key exporters of ginger.

Retail prices of garlic in the US, which imports two-thirds of its garlic from China, reached their highest levels since 2018, driven by concerns that supplies could run short in the coming months due to supply chain restrictions in China. “A sleeve of garlic—which typically contains five bulbs—cost an average of $1.425 in stores during the first two weeks of February, up 29% from a year earlier, according to the US Department of Agriculture,” reads the Wall Street Journal.

There have also been shortages of ginger in China due to the coronavirus, and while supply is growing in the country, the US is currently restricting imports of it, nearly doubling prices, according to FreshPlaza.

With fears of farmworker shortages on the West Coast of the US and across Europe, combined with supply chain challenges, should we expect prices of fruits and vegetables to increase?

A mixed (fruit & veg) bag

After a peak in demand and prices of fresh produce during the first days of the crisis, both are stabilizing as overstocked consumers reduce their spending and growers feel the hit from a reduction in demand from the food service and hospitality industries. Moreover, the international logistic headache and ongoing concern about labor shortages has started to hit the fresh produce industry that is on a strict planting, harvesting and logistical schedule that cannot be adjusted at will.

According to the Produce Marketing Association, sales increased during the peak 30-40%, over the comparable week in 2019. The biggest winner being potatoes (114%), berries (23,5%) and onions (68%). (Check out the chart here on page 3). But the situation has changed and there’s been a decline in demand for berries and pineapples while at the same time an increase in demand for kiwi and apples. A recent virtual roundtable hosted by PMA could not explain the sudden shift in demand, although suggested it could be down to the perishability of the different produce or consumer misconceptions about the safety of the different products. (I recently discovered there’s more vitamin C in a kiwi than an orange and my husband clearly did too as he bought kiwis for the first time ever last week; maybe this was widespread!)

It’s been a rocky ride for avocados, hit by a decline in demand from food service clients. In one week, prices fell 18% in the US but in an attempt to curb further drops in price, Mexico exported a whopping 70% less avocados the following week; harvesting avocados is not as urgent as other fresh produce categories. It’s a similar tale in Europe where the wholesale market for avocados is suffering and prices remain below 209, currently around 11% lower.

The United Fresh Produce Association estimated that the overall produce industry will take a $5 billion hit from the Covid-19 outbreak. Its president and CEO Tom Stenzel wrote that “restaurants and other foodservice outlets account for as much as 40% of fresh fruit and vegetable sales” and that it’s unfathomable to be shifting that amount to retail outlets.

Spirulina?

My colleague Richard Martyn-Hemphill has also read that algae has virus-fighting properties and has been stocking up on that, though it’s hard to know whether prices of spirulina, the most popular form of consumable microalgae but still an incredibly niche commodity, will be impacted. (Algae producers! Are you noticing an uptick in demand? Let us know! Email [email protected].)

Our Singapore-based reporter Jack Ellis has noticed a spike in the price of onions, typically imported into the city state from India that’s restricting the movement of an increasing amount of goods out of the country. Have you noticed pricing changes at the supermarket? Are you eating more or less of certain foods, for availability or health reasons? Let us know! Email [email protected].

Additional reporting from Sofia Ramirez and Richard Martyn-Hemphill.