Insa M. Mohr is founder of Offbeast, a US-based startup making plant-based steaks. A former strategy consultant in BCG’s healthcare practice and associate director of strategy and innovation at Merck, Mohr is co-inventor of a pending patent for the manufacturing of plant-based whole cuts.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent those of AgFunderNews.

Disclosure: AgFunderNews’ parent company AgFunder is an investor in Offbeast.

When I went through Y Combinator, we were all told to raise as little money as necessary. The advice was to “stay small and nimble” for as long as possible. So it came as a surprise when a group partner later told me that this rule didn’t apply to me, a new foodtech founder:

“Foodtech companies need a lot of money.” Maybe it’s just me, but needing huge funding in a time where capital is drying up sounded terrifying.

As for many founders, my favorite startup book back then was The Lean Startup by Eric Ries, the founders’ bible that teaches you to test quickly and avoid building anything unnecessary.

But while the book is full of examples related to software products, applying those principles to foodtech felt almost impossible to me and many fellow foodtech founders.

Yet, over time, I learned that running a lean foodtech company is somewhat possible with the right strategy and I want to share my lessons.

Why it’s hard to stay lean in foodtech

There are countless reasons why building a foodtech company is slow and expensive. Experiments take time. FDA approvals take longer. You need to buy hardware. or worse, build your own.

On top of that, many foodtech startups face another major challenge: they need to operate like deep tech companies and consumer companies at the same time. For many breakthrough technologies, going B2B isn’t an option in the beginning, since the market for their technology doesn’t exist yet.

This creates a mammoth task: Developing novel technology and scaling manufacturing already strains resources; adding consumer marketing on top makes focus incredibly challenging.

Thus, I’d be lying if I said I don’t envy software founders at least once a week. Still, I’ve somehow made running a food company work. Here are five needle movers:

1 – Reduce the cost of consumer tastings

External tastings often start at $10,000-15,000 per test, a large burden for an early-stage company. Therefore, the obvious first step for your foodtech startup are small in-house panels.

At an early stage, any feedback is still better than none, so a group of ten or twenty tasters can already reveal key insights.

When you outgrow that stage, look to university food-science departments for consumer panels. Many are non-profit and offer high-quality tasting panels at a fraction of the price. As rates and approval times vary, you’ll need to shop around a bit.

Another option is working with food-testing companies like Palate, which run tastings in real-life settings and can work within most startup budgets.

At Offbeast we ended up paying about $2,500 per 50 panelists with a Southeastern university and got great insights.

2- Go direct to consumer

Even better than paying for receiving feedback, is being paid for feedback. Therefore, once consumer panels react somewhat positively, start selling directly. I promise you that nothing beats direct feedback from real paying customers!

If you are unsure whether your product is ready for launch in D2C yet, remember the startup credo: “If you’re not a little ashamed to charge for your early product, you launched too late.”

Start by selling small quantities to your most excited customers.

At Offbeast, we started by selling to restaurants but learned that this yields more limited and delayed feedback. Starting to sell D2C enabled us to get direct in-depth feedback! Every new product launch in D2C was like a small focus-group with customers reaching out to us on our feedback form, on Instagram and email or even through phone calls or text messages.

Typically, about 10–25% of early customers are willing to give feedback. We increased our response rate by (a) adding a QR code linking to our feedback form in each package, (b) sending a follow-up email one week after shipping, and (c) offering a $100 Whole Foods gift card giveaway.

3- Make scrappy packaging (even if it’s ugly)

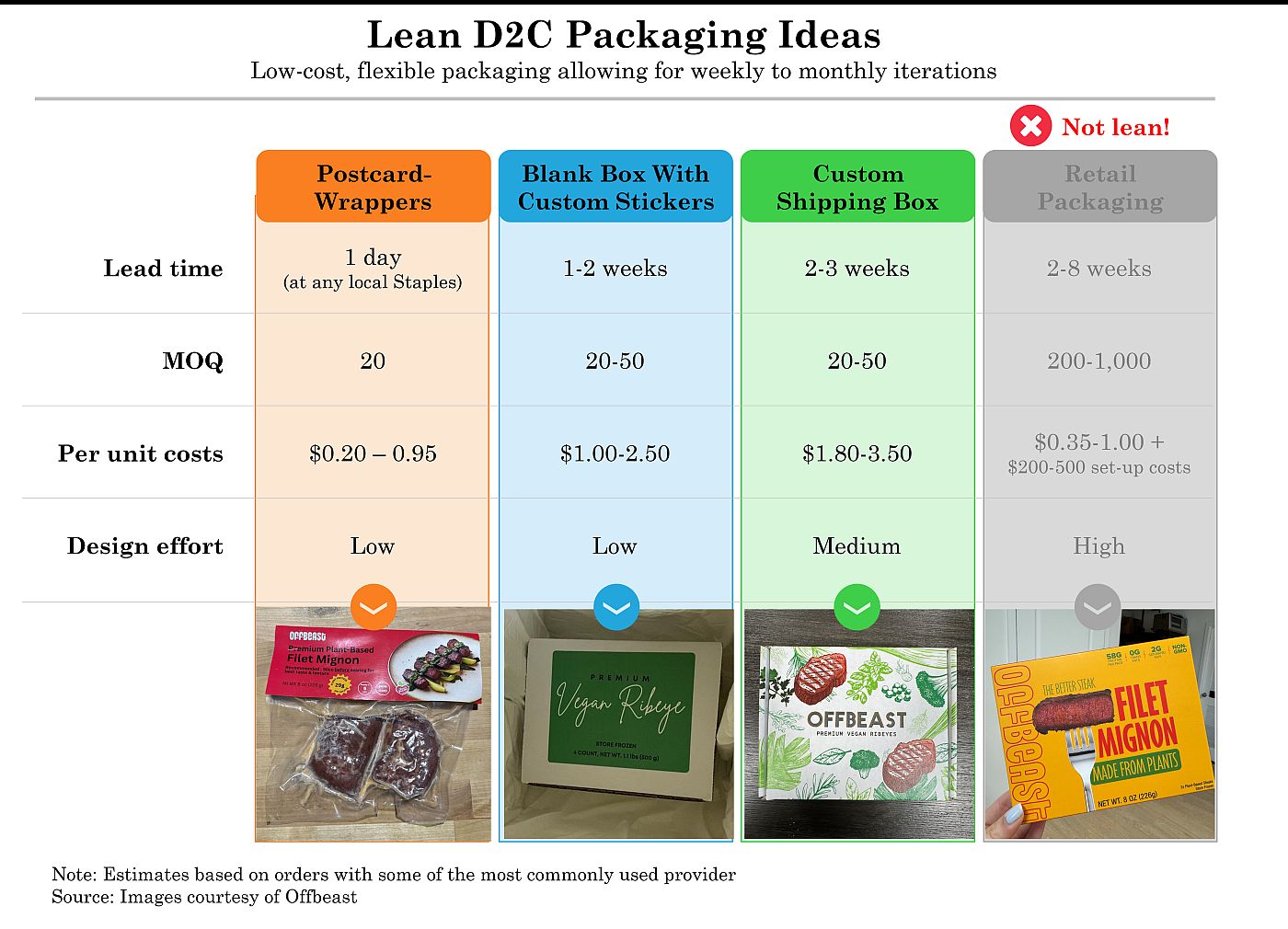

Once you start selling D2C, don’t fall into the trap of overspending on fancy packaging early on. It’s one of the biggest bottlenecks in early-commercialization that I’ve seen and my favorite pet peeve.

Designing and producing your own packaging is slow and costly and often demands minimum orders of 500 units or more – far too many! Much of the feedback you’ll get early on can be addressed by improving elements of your packaging such as cooking instructions and labeling, so printing expensive packaging locks you in and slows improvement.

Instead, create minimal viable packaging you can update every week or two.

At Offbeast, switching to scrappy packaging was a gamechanger. Our first D2C packaging consisted of custom shipping boxes and stickered mailers that took around two weeks to produce. As this turned out to be too slow and too expensive, we switched to simple postcards that we printed overnight at our local Staples.

This allowed us to iterate our packaging in real time. When we learned that some customers were overcooking our initial product version, we tested several bold disclaimers on the front and clearer cooking instructions on the back the next day. Feedback about overcooking

dropped to almost zero within weeks. This bought us time to improve the underlying product characteristics that caused this feedback in the first place.

Was our early packaging pretty or polished? No. Did customers care? Absolutely not. In hundreds of feedback submissions, only two people ever mentioned the packaging negatively -and one of them was a graphic designer offering their services.

4 – Invest in a lean product cycle

If customer feedback can’t be addressed with better cooking instructions or labeling on your packaging, you need to work on the product. Unfortunately, foodtech iteration is famously slow, but it can be accelerated by holding off on building manufacturing hardware and by accelerating development cycles.

The biggest mistake I have seen is building process hardware too soon. This is because you don’t know what hardware you really need until the product is validated. Yet, building hardware is expensive, slow, and most often requires specialized hires. So, hold off with building hardware as long as you can and test processes manually first.

Unless absolutely crucial to your process, you should hold off with building custom equipment until you sell enough volume to build your first pilot factory.

In addition, you can significantly accelerate development cycles by building a strong testing infrastructure. At Offbeast, stepping back to rethink how we run tests reduced our product development cycles from six months to 1-2 months.

We did this by creating a “test dummy” – a minimum viable prototype that let us test early new ideas without having to manufacture the full product. This allowed us to iterate through far more samples, far more quickly.

5 – Shift to commercialization at ‘good enough’

Early on, almost your entire team might consist of food scientists spending nearly all their time running experiments. Once you find product-market fit, however, it’s time to focus on commercialization. At this stage, you should still collect feedback and make improvements, but changes become smaller.

Unless you’re heavily funded, this is the point where you need to move resources toward scaling and selling. At Offbeast we started with a full team of food scientists, but then temporarily reduced R&D to just half of one employee dedicated to R&D, with the rest moving into operations and business development roles. Nevertheless, thanks to our lean testing infrastructure, we were able to launch new products or product variations every 1-3 months.

👉 My advice to foodtech founders: Yes, more resources might help you grow faster. But that luxury isn’t available to many foodtech companies today. Building a lean food startup by focusing on affordable ways to improve your product can stretch your runway to profitability, or at least to the next funding round.