It’s no secret that capital is constrained right now in the agtech world, making fundraises difficult for startups and causing more than a little uncertainty over future growth of the sector. When it comes to ag robotics and automation, this is especially true.

At the same time, the need for solutions that can alleviate labor shortages and create more efficiency on the farm cannot be overstated.

And despite the capital crunch, many remain optimistic about the agtech sector.

“We believe this could be a strong vintage year for funds and investors, as valuations are now more reasonable than they were during the height of the zero interest rate environment,” says Arthur Chow, principal on the food & agriculture investment team at S2G Ventures.

”As other investors pull back, we see an opportunity to be more risk-on, finding companies focused on building enduring businesses that have a commercial path to profitability.”

The ‘expectation mismatch’ in agtech funding

Ag robotics and automation have certainly seen some bright spots in the last few years. Israel’s Bluewhite recently struck a deal with CNH to bring autonomy capability to tractors under the Blue Holland Brand. GUSS, which makes autonomous spraying applications, is getting to scale on the west coast, mainly in orchards, and also has a partnership with John Deere. Other notable companies working in this space include Carbon Robotics, which snagged a recent investment from NVIDIA’s venture arm, Advanced Farm, Stout Industrial Technology, Burro, and farm-ng, to name a few.

“These are ‘transition-phrase companies’ that have proven their technology, raised a certain amount of funding and are in the market with plans to expand,” says Walt Duflock, SVP of innovation for Western Growers (WG).

“In the past, when automation startups reached these milestones, they were able to build on those successes through additional funding from equipment manufacturers like John Deere and New Holland or from venture capital.”

By and large, however, capital is hard to come by right now for such companies, whether it’s coming from OEMs like John Deere or from venture capitalists.

Funding to the AgFunder-defined Farm Robotics, Mechanization and Equipment category declined 21.1% in H1 2024, partly thanks to an overall drop in agrifoodtech funding over the same time period.

Some industry experts say this slowdown could possibly extend through 2025 and into 2026.

Chow says one of the key issues right now when it comes to funding is “the expectation mismatch between the adoption cycle in agriculture compared to typical tech like enterprise SaaS, which generally scales much faster.”

When hardware is involved — as it usually is in robotics and automation — product pivots are more complex, costly and time consuming, he adds.

“Investors also tend to seek a base of sticky, recurring revenue, but in the agricultural sector, equipment is often viewed as a capital expenditure rather than an operating expense. From what we’ve seen, growers prefer to buy equipment outright rather than paying recurring fees, whereas Silicon Valley investors are more focused on annual recurring revenue.“

Exits in agtech, too, have eluded most startups, which he says is leading generalist investors to chase DPI and direct their money “towards areas with stronger returns,” particularly as pressure from LPs to return capital mounts.

‘Build with the farmer in mind’

How should startups approach the ag robotics and automation industries?

“Build with the farmer in mind and focus on real farmer challenges early in the product development process,” says Leanne Gluck, head of education innovation at robotics startup farm-ng.

“It is very likely that in the next 3-5 years, the market will evolve into a more consolidated ecosystem. It’s important for startups to understand their core IP and what will become a commodity.”

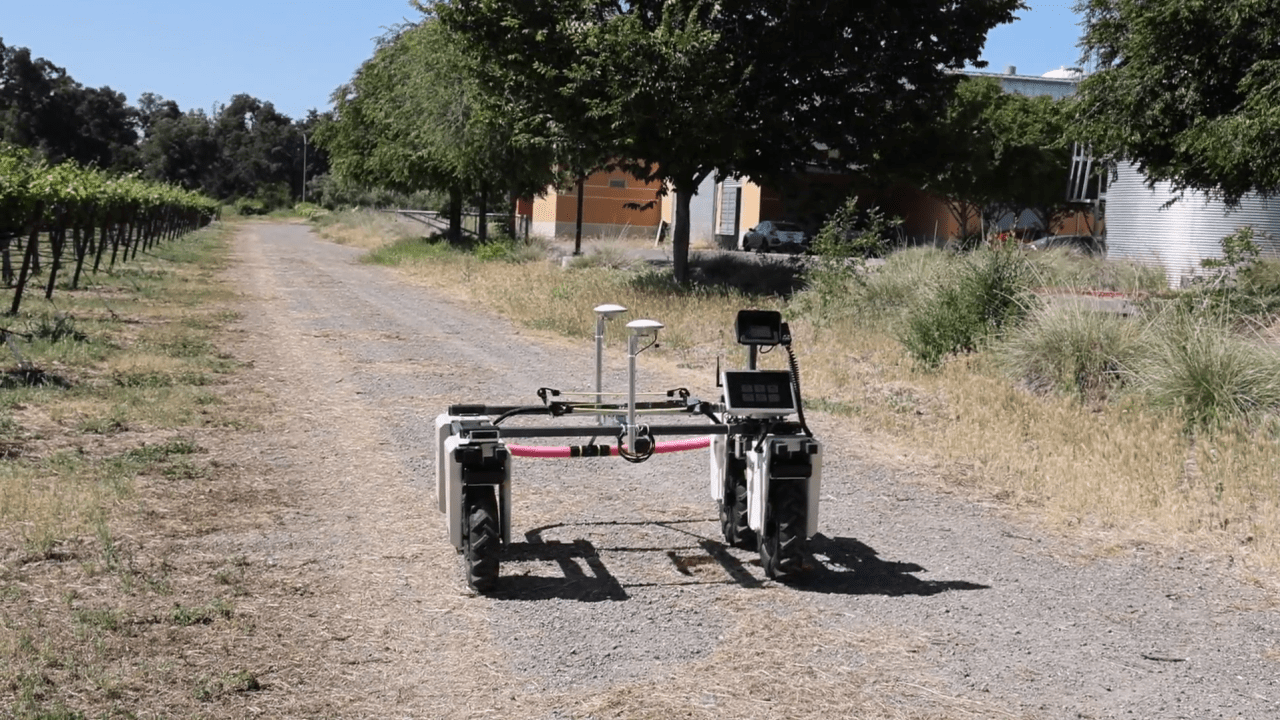

Farm-ng, which raised a $10 million Series A at the start of 2024, has developed an autonomous machine that aids humans with a range of tasks on the farm including soil preparation, planting, harvest and crop care, amongst others.

“Our strategy is centered around in-market revenue generation and delivering real, tangible solutions that address farmers’ needs,” says Gluck. “As long as the business fundamentals are strong and we are delivering solutions to happy customers, it doesn’t matter what is happening from a macroeconomic perspective, because there will be capital that will be able to support businesses that are meeting customer needs.”

Gluck suggests navigating the current funding winter “by focusing on what matters most: building a best-in-class modular robotic platform with exceptional software and robust autonomy capabilities.”

Weeding is currently the most popular task on the farm to automate, but Gluck says automating can depend on which farmer a startup talks to and the unique challenges they face.

Some focus on weeding. Others “prioritize automating tasks that impact the well-being of their workers, like spraying pesticides.”

Other regenerative agriculture-related tasks like compost spreading or beneficial bug spreading could be accelerated through automation, as they require time, physical labor and complex management practices, she says.

Chow adds that “Startups also need to find the balance between delivering immediate value with a product that may have limited use cases today while also building products that could address a larger market that will excite VCs.

“A common criticism we hear of many ag robotics companies is that they offer only point solutions, or robots that excel at performing a single task. This focus is critical in hardware and automation, as it’s too expensive and hard to build a machine that tries to do everything but nothing particularly well.”

A bootstrapper’s market?

In the meantime, it may be an ideal market for bootstrapped endeavors, suggests Duflock, referring to those who have ideas but aren’t necessarily at the point where they need capital.

“If you’re in a position where you can start a very technically skilled founder team and you can bootstrap stuff for a couple years, you may be able to create a disproportionate amount of value.”

“Don’t wait for the market to reset to get started innovating,” he adds.

Mid-stage startups, bootstrapped operations and everything in between will face different sets of challenges, but a few things remain consistent across the industry, and hopefully hint to a light at the end of the funding winter tunnel.

As Chow points out, farm labor remains costly and scarce — a problem that isn’t going to change in the future. Because of this, growers are trialing new technologies, and strategics have shown interest in tools like AI, he says.

“We’ve seen that companies are now more focused on operating efficiently, reducing burn, and achieving profitability, as capital constraints have instilled greater discipline.”

The most promising companies may also be those that show growth in ag but also paths towards applying their autonomy towards bigger and bigger markets in agriculture and beyond,” he suggests.

Gluck likens surviving the current market to what happened some years ago in the self-driving industry.

“The survivors of the self-driving era are also the ones who created the right partnerships and did not do everything themselves,” she says. “ The same trend will happen in agtech. The companies that are going to win are the ones that win together.”

Innovating to meet these needs while navigating the bumpy terrain of current agtech financing will be a key theme at this year’s FIRA USA show, taking place October 22 – 25 in Sacramento, California.