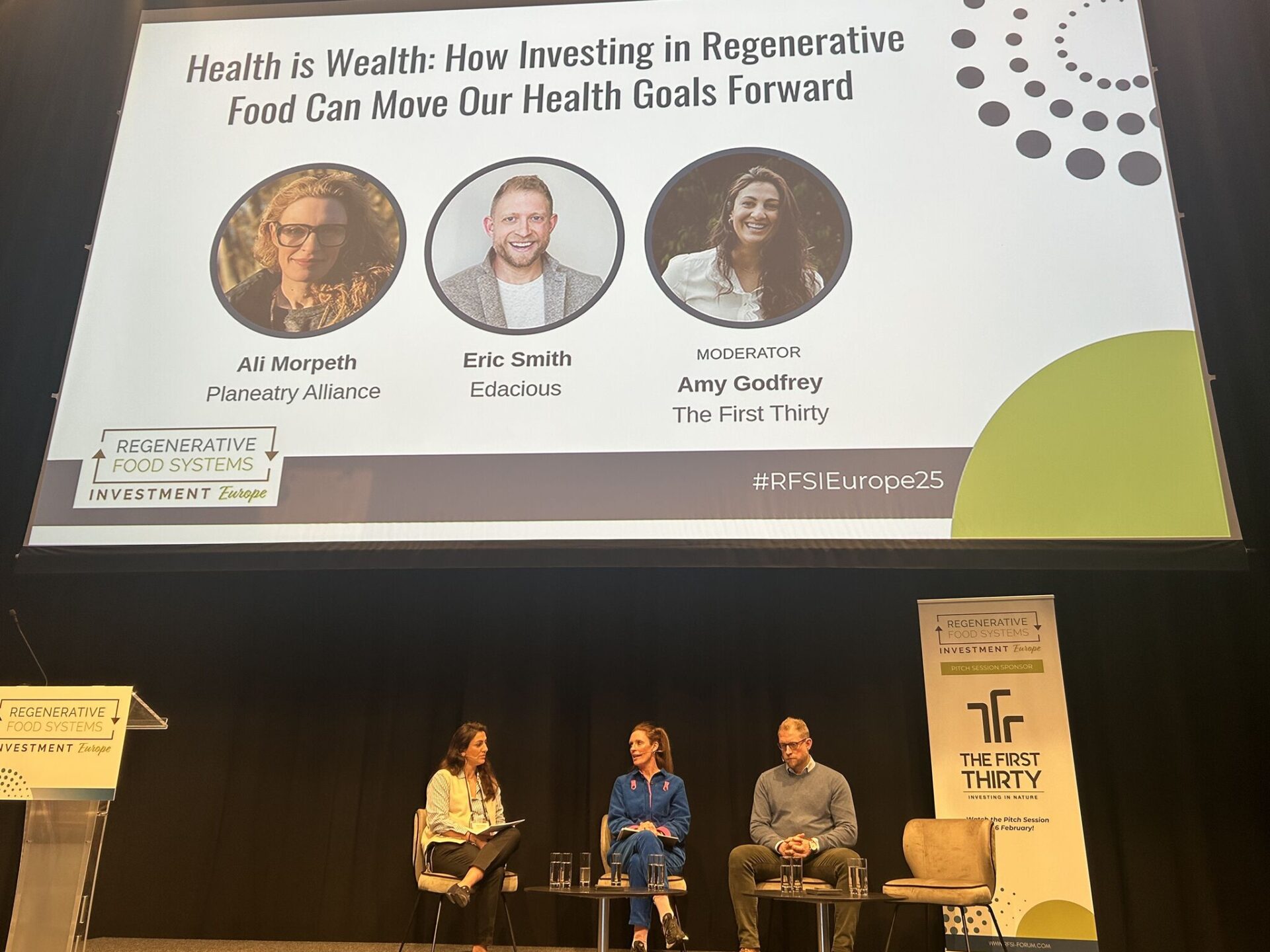

What prompts a doctor to turn to become a VC? For Dr. Amy Godfrey, it was witnessing a never-ending stream of patients with chronic disease that could largely be traced back to food.

“I knew from my training that nutrition was important, but had no knowledge of the damage our food system is doing to our health,” Godfrey, an analyst at VC firm The First Thirty and a doctor with the UK’s National Health Service (NHS), said in a recent conversation with AgFunderNews.

As a medical professional, Godfrey witnessed everything from limb amputation related to chronic disease to five-year-olds with type 2 diabetes.

Unable to “unsee” the damage, Godfrey began studying the concept of a regenerative food system and the central role human health plays in it. The path eventually lead to The First Thirty, a London, UK-based VC firm that invests at the intersection of human health and regenerative food systems.

Below, Godfrey discusses her journey along with what it will take—for consumers, corporates, and everyone in between—to build a better food system.

AgFunderNews (AFN): What took you from the medical field to venture investing?

Amy Godfrey (AG): Venture is not a field that I ever thought that I would work in, coming from a medical background. But I think what has really piqued my interest about venture capital is that you’re really involved at the beginning of an innovation. I like the idea that we can build a portfolio of companies that will represent what the food system could be like.

I was an anesthetics and intensive care medicine doctor in the NHS for seven years. I don’t think it’s any exaggeration to say that I learned little to nothing in medical school about nutrition, sleep, and exercise being the pillars of health.

Then I read [Chris van Tulleken’s book] Ultra Processed People, and I thought, Is the food system really that bad? Is it contributing that much to illness? I obviously knew from my training that nutrition was important, but had no knowledge of the wider system, the contribution to climate change and the extent of the damage our food system is doing to our health.

After that, I just could not unsee the food-related disease in my patients. Every week, there would be a patient coming in for some kind of limb amputation related to type two diabetes. I felt like I was failing as a doctor, because that is far too late for me to play a positive role in diabetes management.

I read more about food and about the impact of the food system on the planet and our health. I realized we’re facing a two-birds-one-stone situation: With food, we have the opportunity to fix our two biggest crises, which are that both people and planet are incredibly sick.

I felt like I had to explore this further: Was it possible to move from a disease-causing to disease-preventing food system? So I went to Groundswell and met Antony from The First Thirty there. I was kind of blown away by how much they had already thought about what a new food system would look like, what were the steps needed to get to that new system and what the potential human health impacts might be.

They had decided that the human health opportunity was probably a big one and one of the levers that we could pull on to drive change. Whilst the team has amazing expertise in lots of areas, it didn’t have the domain expertise in human health, so I think it recognized that it would be useful to have someone from the medical field onboard.

AFN: Agrifood corporates are a big part of the regenerative food discussion nowadays. How can we leverage health to get them more committed to the regen transition?

AG: So much of the food system is driven towards ultra-processed food by massive companies who really don’t care about what we think.

We do need the corporates to move, but I think that will be a byproduct of the data and evidence that we [the regenerative agriculture industry] provide.

First, I think we will start to better quantify how much food-related disease costs. Because if you had a company generating the kind of profits that could offset food-related disease, it would be a unicorn tomorrow.

For example, in the UK, one patient with diabetes on average, costs the National Health Service £25,000 [$33,000] per year. That amounts to around 10% of the entire NHS budget being spent on type 2 diabetes. That’s billions of pounds a year on an entirely preventable disease.

So once we start to quantify those health costs and can put them down to food, that will start to shift things. Also, in the UK at least, we’ve never seen rates of economic inactivity as high as they are at the moment—that is, someone is neither in a job nor looking for a job.

While there are a lot of reasons for that (e.g., you could be a stay-at-home parent), the biggest reason is chronic disease.

There are lots of chronic diseases that genuinely can’t be managed to the point that someone can work, but there are also a lot of them that are lifestyle related. So this is not just a healthcare cost, this is a GDP cost. I think that private companies will start to see that their workforce is less productive, that they’re off sick more, and they will start to see health of their workforce as an asset that they should invest in.

If those two things—health costs and loss of worker productivity due to health—align and start to affect profit margins, the needle will move.

I do hope that the big food companies will start to come along for the ride, because they will see that there’s a financial incentive for them to be part of the solution, not the problem. At the moment, they’re only incentivized to be part of the problem because people buy the stuff on their shelves. When that changes, then maybe we’ll start to see regen brands will be acquired by big food, and that will start to incrementally move them in the right direction.

AFN: What about educating the average consumer on the benefits of a regenerative food system?

AG: Where my area of expertise lies, it’s about the flow of nutrients from soils to crops or animals to humans. That’s really hard to ignore, but it’s also a very difficult message to convey to consumers.

Lots of people eat conventionally grown apples; I would like to know how many of those people would eat the apple if I sprayed it with glyphosate in front of them and then handed it to them to eat?

I bet the answer is way less.

So there’s a need to find the hidden information that we need to bring to the forefront for people to be able to make informed decisions.

People are much more aware of chemicals going on their food than we give them credit for now. There’s also the question of what our food currently does not contain. This is where the nutrient density conversation starts, and where soil is kind of magical.

If you have a healthy soil ecosystem, then there’s a massive range of nutrients that can flow into crops. If you eat those crops, they’ve flown to you. And if the animals eat those crops, and you eat those animals, then it also flows into you.

It really hinges on the soil, much more than I had ever appreciated until quite recently.

The missing bit for consumers is nutrient density. The question is, how do we repackage that in an understandable and approachable way. Is it food labeling? Is it advertising?

AFN: Taste often comes up in that conversation. How big of a role does that play?

AG: One of the massive things we often overlook is that people largely eat food for enjoyment. Yes, we have to eat to sustain life. But once you’ve got that bit out the way, most people will eat something that they enjoy. One of the dirty secrets is that we used to use taste as a very good surrogate for health. One-hundred years ago, if you ate something that tasted good, most likely it was probably pretty good for you.

Today, ultra-processed food is delicious because it’s designed to be hyper palatable, to have the perfect texture for you to reach that so-called “bliss point.” So I think we’ve lost the ability to use taste as a marker of health.

One of the other big things about changing consumer behavior is that you’re never going to get people to not pick up a chocolate bar that’s made of all of these chemicals and eat that in preference to, say, a regeneratively grown apple.

How do we change this? Some of it is exposing the extent of the health crisis. Most people care about their health and the health of their loved ones—maybe not enough to always change their behavior, but enough to make some marginal gains.

People need to understand that ultra-processed food is designed to be addictive. It hijacks your brain, your reward systems. Plus, most people are sitting at their desks or they’re on the move and need to get lunch quickly. But fast food doesn’t have to be unhealthy food.

In the UK, about 15% of school starters—four- and five-year-olds—are Type 2 diabetics. So the education piece has to start really early. It should be in schools. It should be in homes, because what do 30- and 40-year-olds look like when they have been diabetic from the age of five?

So the consumer behavior part is a big one, but I don’t think it’s the only piece of the puzzle. Like we talked about earlier, Big Food has a huge responsibility here.