With demand for coffee expected to dramatically exceed supply as climate change impacts key growing regions, a flurry of creative solutions has emerged, with startups exploring everything from bean-free alternatives and more robust coffee plants to coffee made via plant cell culture.

But does it make sense to grow a commodity ingredient such as coffee from plant cells in bioreactors, or does this approach only make sense for ultra-high-value botanicals such as saffron?

What is plant cell culture?

Rather than using sunlight, water, and soil to nurture fully-grown plants, firms using plant cell culture grow plant cells in bioreactors. The primary feedstock is sugar, although more expensive ingredients are required to elicit cells to differentiate into certain cell types.

The technology is already used on a commercial scale to produce cancer drugs Paclitaxel and Docetaxel (which contain a bioactive found in yew tree bark that Phyton Biotech makes via plant cell culture) and Elelyso, a drug used to treat Gaucher’s disease (which contains an enzyme produced by Israeli firm Protalix in carrot cell culture).

However, using the tech to produce food and supplement ingredients such as vanilla, aloe vera, lemon balm, cocoa flavanols or cannabinoids is relatively new, with a flurry of startups jumping into the space over the past few years as botanical supply chains have become increasingly threatened.

Growing coffee in bioreactors—currently being trialed at small scale by startups including STEM in France and California Cultured in the US—is seen as especially challenging given the large volumes involved and relatively low prices compared to, say, saffron or vanilla.

However, Israeli cell therapy specialist Pluri reckons it can make economic sense with the right cell lines and technology.

Pluri: ‘We can do this at cost parity in a very timely manner’

Speaking to AgFunderNews after unveiling plans to spin out a plant cell-derived coffee business (PluriAgtech) as a new subsidiary led by Michal Ogolnik, Pluri president and CEO Yaky Yanay explained:

“We’ve designed a system that at scale can basically replace about 1,000 coffee plants, and that’s a big number. Plus we can make a batch of coffee in about three weeks, whereas you can only harvest coffee from trees twice a year.

“If we do this at scale, we can do this at cost parity in a very timely manner. We also have a significant competitive advantage [over early-stage plant cell culture startups] because we’ve been working with human, animal, and plant cells at scale for a long time,” added Yanay.

Pluri, he said, has two decades of experience in large-scale cell cultivation working on cell therapies for regenerative medicine and more recently on cultivated meat via a spin off company called Ever After Foods backed by Israeli food co Tnuva.

“So for us, it’s not just a theoretical exercise, we can produce hundreds of kilos in our labs. This is not something that we intend to develop in five years’ time; we know how to scale this process.”

He added: “We are able to get a population of cells that has the capacity to proliferate very significantly. It’s quite shocking to see the amount of cells we can produce. We are using the same [bioreactor] systems for the plant cell systems, but we are adjusting the process and conditions to what the plant cells need to be at their best. We have also hired experts in the field to establish the biology of the [coffee] plant and build cell banks. Our development team is then able to take this all the way though to process development and manufacturing.”

The process: ‘We’ve focused on cell lines with significant proliferation capacity’

In a nutshell, Pluri takes samples from multiple parts of the plant including the leaves, triggers them to return to a stem-cell-like state, and then grows them in sugary culture, said Yanay, who will not disclose all the media components.

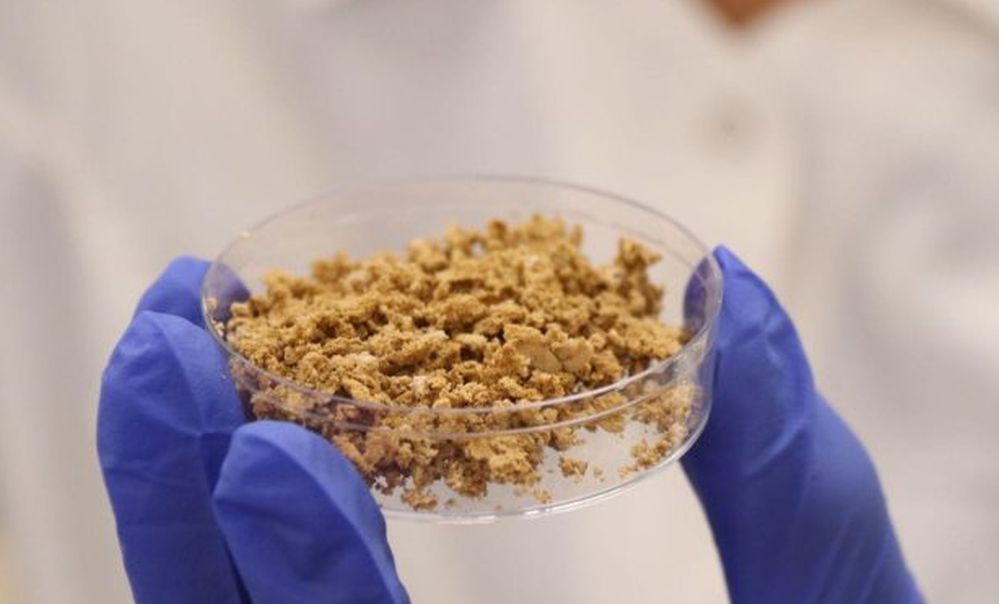

“We’ve focused on cell lines with significant proliferation capacity and we push them to differentiate into the bean-like cells. They grow in aggregates and then we harvest the biomass and dry and roast them.”

As roasting cell biomass is not the same as roasting regular coffee beans (the biomass is more fragile), Pluri has had to come up with a gentler approach in order to protect its coffee, added Yanay. “We use a less aggressive method, which is beneficial in that it uses less energy and it’s a shorter process.

“The end product looks, smells, and tastes like ground coffee you buy in the supermarket, and what’s quite amazing is that we can control parameters such as the level of caffeine in the final product by modifying the growing conditions, so we’re doing that without genetic engineering, just by changing conditions in the bioreactor.”

The go to market strategy

Rather than getting into the consumer coffee business, he said, PluriAgtech will build partnerships with coffee players to take its products to market.

“We have had significant interest from the market, and for us, it’s really important to work with partners that are experts in the market, that understand what the product should look like and how to position it.”

From a regulatory perspective, he said, “The GRAS [the Generally Recognized as Safe] pathway makes sense as the US is one of our primary markets. But we also have interest from other territories and I believe there are quite a lot of opportunities globally.”

The rationale: ‘The coffee industry is facing quite a significant crisis’

While coffee—like chocolate—is an affordable luxury right now, things are changing, he said.

In part due to climate change, he noted, the amount of land that can sustain coffee is dropping, while Arabica—the favored species— has weak genetic diversity and only grows at certain temperatures, which means moving to higher altitudes as temperatures rise.

“The coffee industry is facing quite a significant crisis. Basically, by 2050, the land suitable for growing [Arabia] could be reduced by 50%, which means we’re going to see a significant reduction in production.

“The other option is basically to go up in elevation to higher altitudes, which contributes to deforestation. Coffee is also a huge consumer of water, and it used to be that growers would rely on rainfall, but now in some regions they are having to water [irrigate] the land, which wasn’t the case even 10 years ago. So things are changing fast. Meanwhile, demand for coffee is also rising [particularly in large markets such as China and India].”

He added “We’re not on a mission to replace the coffee industry. We are trying to fill a gap. We’re talking about a 50% loss of a $130 billion industry [if nothing changes between now and 2050] so we see a massive need.”

Further reading: