This week, UN Secretary General António Guterres warned of a “global food shortage” that “threatens to tip tens of millions of people over the edge into food insecurity followed by malnutrition, mass hunger, and famine.” Andrew Bailey, Governor of the Bank of England, described skyrocketing food inflation as potentially “apocalyptic.”

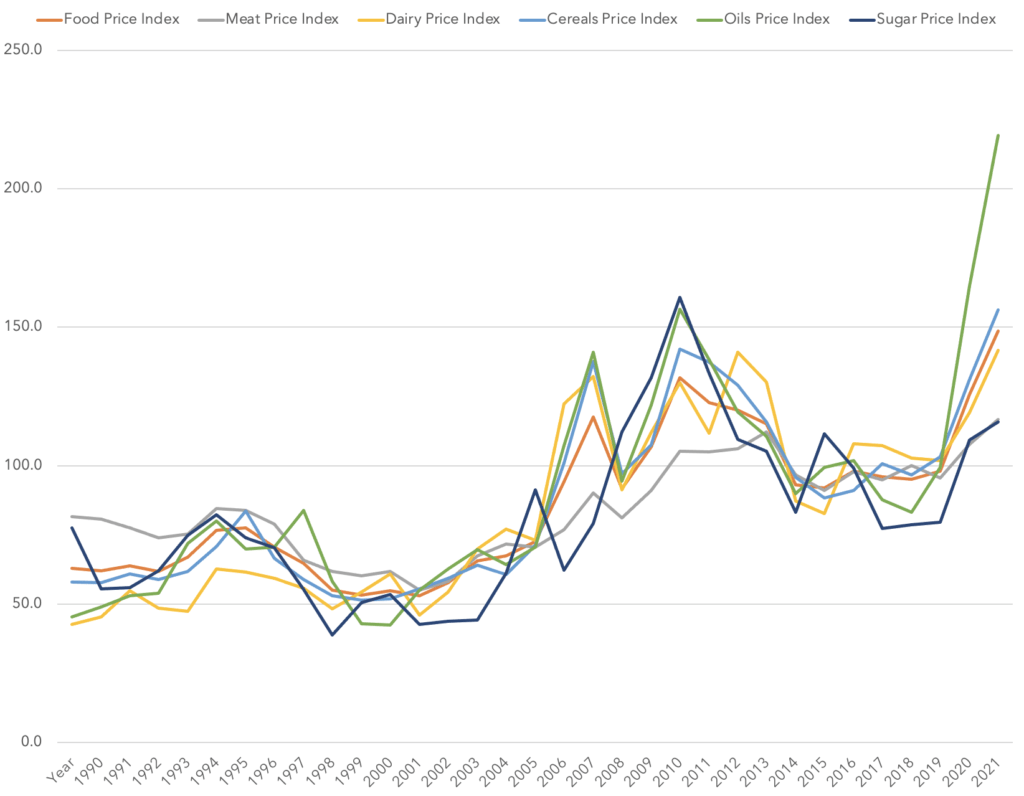

Across the board, the prices of key agricultural commodities — from grains to oilseeds, to meat, dairy, and sugar — are rising at breakneck speed. In fact, global ag commodity prices hit an all-time high in March this year, according to the UN Food & Agriculture Organization‘s Food Price Index. While the Index dropped slightly by 0.8% in April, it was still up an eye-watering 30% year-on-year.

“We just don’t have a lot of the basic goods and commodities stored up across the world, so it doesn’t take much of a shock to send prices moving upwards,” says Emma Weston, co-founder and CEO at online grain management platform AgriDigital.

“And if you think of all the various shocks we’ve had lately — climate, war, Covid-19 — we definitely are in the eye of the storm at the moment,” she tells AFN.

It’s difficult to “see any end to this high price environment for at least six months, and probably longer,” adds Kona Haque, head of research at commodities and securities brokerage ED&F Man. “Supply-side effects filter down and just perpetuate the situation,” she tells AFN.

What are these ‘supply-side effects’?

War

This won’t come as a surprise to many, but Russia’s invasion of Ukraine starting in February 2022 has proven to be a major exacerbating factor in the food price crisis.

Ukraine is among the world’s top producers of wheat and corn, and leads the production of sunflower seed oil (it also turns out that it’s a major source of tech talent for the global agtech industry.) Emerging markets, in particular, rely on Ukrainian wheat exports.

The ongoing February invasion is not only crippling the country’s ability to export its stores of grain and other commodities overseas, but also its capacity to plant for future growing seasons. Much of the Ukrainian population, including most men, have been mobilized for combat – leaving fields untended, crops unharvested, and seeds unplanted.

Nevertheless, Ukraine is sitting on an estimated 22 million tons of grain in silos and storehouses, just waiting to be transported. But logistics is still a problem.

FAO Food Price Indices 1990-2022

Usually, the vast majority of grain, and other ag commodities, produced in Ukraine are exported by ships via the country’s Black Sea and Azov Sea ports. But all of these are under blockade by Russian naval forces, preventing the movement of any marine traffic.

“The fact of the matter is that many of the ports have been destroyed, warehouses have been destroyed, and there are no men available to plant and farm,” says Haque. “We have to assume that 20-30% of typical supplies will be lost this season. And there are huge question marks over planting the next crop for the summer,” she told AFN.

There are potential alternate routes out of the country — for example, through its relatively unscathed western borders with the EU — but here, legacy issues frustrate efforts to get grain moving.

Ukraine’s railways were built during the Russian Empire, which adopted a different track gauge to most of the rest of Europe. As such, trains cannot cross directly from Ukraine and into Poland and Romania; they either have to have their cargo unloaded and reloaded onto different trains, or have their bogies swapped to fit the local tracks.

Moreover, the fact that the sea has historically been the main route for Ukrainian grain imports to Europe and elsewhere means that the rail infrastructure to the west is ill-prepared to suddenly and vastly increase its capacity.

In April, it was estimated that just over half of Ukraine’s total potential rail capacity was being used; with 39% being used to move grain.

Fert frustrations

Russia is also among the leading producers of grain; but with an increasing amount of its resources being sucked into the “special military operation,” as President Vladimir Putin calls it, and facing the most stringent package of international economic sanctions ever implemented, its capacity to export produce has also been severely limited.

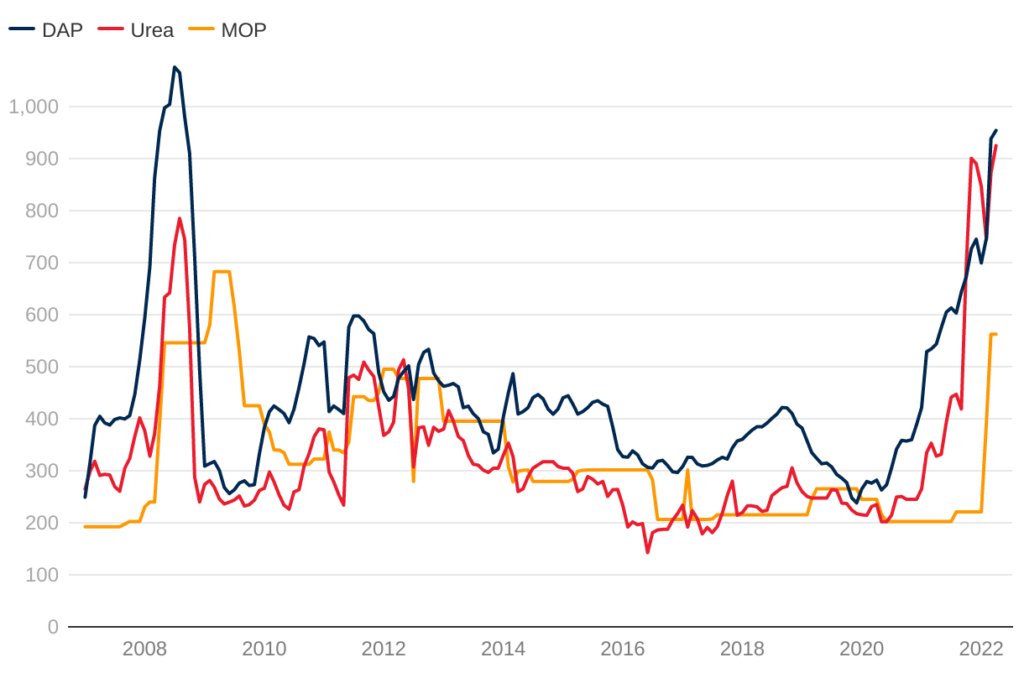

Then there’s fertilizer. Russia is overall the leading exporter of fertilizer ingredients, accounting for 23% of global ammonia exports, 21% of potash exports, 14% of urea exports, and 10% of processed phosphate exports, according to the Fertilizer Institute.

But the country has effectively ceased any large-scale exports, while sanctions have further disrupted the agro-chemical trade. (Ukraine has also banned the export of fertilizers; while neighboring Belarus, another major potash producer, has been hit by sanctions since it is Russia’s closest ally and apparently provided staging posts for its invasion force.)

Fertilizer prices 2008-2022, US$ per metric ton

The biggest customers of these chemicals include Brazil, China, India, and the US. While the last of these has substantial domestic production capability, Brazil, for example, is almost entirely reliant on foreign imports of fertilizer.

While Brazil and neighboring Argentina might normally be considered to have the capacity to pick up the slack in the market from Ukraine and Russia, the increasing scarcity of agro-chemicals means they are likely to offer substantially lower yields in the months and years to come.

“Brazil, for example, is having good weather and should be able to plant a huge crop to solve this,” Haque suggests. “But if they can’t access fertilizer — they get over 80% from Russia — how do they nourish their fields?”

And it’s not just export bans from Ukraine and Russia that are having an impact. As the global food situation deteriorates, other nations are taking protectionist action in an attempt to secure their own domestic supplies.

Last week, India — the world’s ninth-largest wheat producer, according to the US Department of Agriculture — said it will stop exporting the grain. A few weeks earlier, Indonesia — the world’s largest grower of oil palms — said that it would not let any palm oil leave its shores for the foreseeable future.

“Food importing governments don’t want to take the risk: they saw what happened in the Arab Spring, when food was 40% of the inflation basket. They don’t want people in the streets,” Haque says. “So the likes of Egypt, Indonesia, and Kazakhstan have started to hoard food supplies and started banning exports.”

Protests over the rising cost of bread were reported in Iran last week.

La Niña

It seems all too easy to blame our current predicament squarely on the geopolitical situation in Eastern Europe. But the fact of the matter is that prices of ag commodities and chemicals had been rising for some time prior to February’s invasion.

For one thing, disruption to supplies out of Ukraine has been an issue since at least 2014, when Russian-backed separatists in the country’s Donbas region began an armed rebellion and declared themselves independent. Around 40% of Ukraine’s wheat-growing capacity lies in the eastern third of the country, including Donbas.

An increasingly volatile climate has also proven problematic for agricultural production in recent years. Since 2020, the world has been in the grip of La Niña – a periodic atmospheric phenomenon that leads to the disruption of normal weather patterns, along with fierce storms in some regions and extensive drought in others.

“That initially led to very dry weather in Brazil and Argentina, and, eventually dry weather events in Russia and Europe,” Haque says. “So key producing regions have been suffering from especially inclement weather.” (Just this week, France has issued drought warnings for most of its regions.)

Long Covid

Beyond Ukraine and La Niña, the other tectonic event that has shaken up food supplies over the past few years is the Covid-19 pandemic.

“Food prices were trending higher even before the Ukraine war. Even if you look back to the beginning of Covid-19, some supply chain hiccups were already leading to rising freight rates, so the cost of shipping goods was already going up,” Haque says.

The worldwide spread of the novel coronavirus — suspected to have originated in the human food chain — led to large-scale lockdowns, the shuttering of factories and warehouses, and the closure of borders and trade routes. Container ships were stuck at sea, while aircraft remained grounded.

In the earlier days of the pandemic, the resulting slowdown in supplies led to panic buying and empty store shelves in many countries. Meanwhile, as the economy struggled to stay above water, millions were forced out of work; either because employers couldn’t afford to keep them on, or because they were compelled to seek alternative sources of income. Positions in the agrifood and logistics industries — including, crucially, truck drivers, ships’ crew, and farmworkers — were, and still are, strongly impacted.

As global lockdowns slowly brought the pandemic under control in late 2021 and into this year, pent-up demand led to a run on goods and shipping – which in many cases, simply hasn’t been met by supply, in part due to the continued lack of workers and heightened costs.

Putin’s invasion of Ukraine won’t just disrupt food supplies – but food technologies, too

According to Weston, Covid-19 laid bare many longstanding problems with inefficiency and a lack of sustainability in the food supply chain.

“Largely our world has evolved into a series of commodity-tiered supply chains, so when there are commodity shocks for whatever reason, that directly influences the price of food,” she says. “Combine that with supply chain shocks, particularly in the Black Sea region, and all on the back of Covid, and you get a perfect storm [for food inflation.]”

Change in direction for agribusiness

A broader issue that was underscored by Covid-19, and again by the war in Ukraine, is that of stockpiles and forward planning.

“Carrying capacity is finite for large commodities,” Weston says. “Let’s just take grain as an example, which has a relatively long shelf life. Even though it may have a two, three, or four-month shelf life, the stock [we have stored globally] to use is actually down to a matter of weeks. So it doesn’t take very much […] to find its way into inflationary pressure, particularly in a rising interest rate environment as well.”

Weston points out that the number of companies running the majority of the global grain trade can probably be counted on the fingers of one hand.

Over time, this “move towards undifferentiated global commodity supply chains has perpetuated the fragility of the system,” she adds. “That’s not to say we don’t need big global traders — they’re vitally important to the world economy and us getting food on the table — but we’ve lost those smaller, differentiated, localized food supply chains. And because we’ve lost that over the decades, we are now paying the price.”

While the infrastructure of large-scale commodity trading may have contributed to the food pricing crisis we’re facing, it may also contain the fastest route to a solution. That was the view put forth by JY Chow, agrifood and retail sector coverage lead, Mizuho Bank, speaking at this week’s Food & Drink Innovate Asia conference.

“If you look at the ag world for the last probably 10 or 20 years, it was all about arbitrage – just-in-time [delivery] and managing [for growth] in very volatile markets,” he said, highlighting the relatively low prices for wheat, corn, and soybean between 2014 and 2019 – which resulted in farmers, particularly those in the US, planting fewer acres in order to scrape a profit.

“In more recent years, it is all about managing your risk: the risk related to food security, the risk related to geopolitics, and the risk which is more financially driven – liquidity and hedging. And also the elephant in the room: Sustainability.”

An opportunity for agrifoodtech – but not a solution to rising food prices

So what does this all mean for the agrifoodtech ecosystem, which just had its biggest-ever year in venture funding terms?

As with the Covid-19 pandemic, many market commentators — including us at AFN — have argued that crises represent opportunities for agrifoodtech innovators to step in and change our food systems for the better.

But for Haque, the current food inflation crisis is unfolding too fast, even for tech.

“Right now, it is all about weather and politics. I’m not sure how tech can affect those in the short term,” she says. “But what these prices are going to do is incentivize more research into new crop varieties that are drought resistant, heat resistant, and so on.”

Weston also admits that her call for differentiated commodity supply chains and more localized food production is a longer-term project.

“There’s going to be very little we can do to avoid [price shocks] in the short term because we have lost physical infrastructure capacity, we’ve lost the participants who add diversity and robustness to supply chains, and we’re not yet at a level of digital adoption for something like AgriDigital to have that kind of global impact,” she adds.

However, she still thinks it’s a once-in-a-lifetime chance for agrifood innovators.

“I think it’s going to take time [but it’s] the perfect opportunity for all types of players in supply chains to think about their cost base [and] not having a lazy supply chain, but an actively-managed supply chain,” she says. “It’s not going to come without some cost, but the alternative is disastrous, so it’s an important investment to make, not just to overcome short-term shocks, but to create a whole new supply chain, resilient for the future. That’s not an investment that will be lost.”